Red is a powerful colour. Red embraces our more positive emotions, but also embodies our concerns and anxiety. It can symbolize energy, action, power as well as love, passion, and beauty. Red, in daily life, is laden with symbolism, and no less so throughout the history of art. In Royal portraits, the monarch is often presented in red robes. The Lucca Madonna (1437) by Jan van Eyck is draped in a rich velvet red gown; the colour red playing an important symbolic role in Christian iconography. Red has never lost its symbolic power; the work of twentieth century artists, for instance, Mark Rothko and Piet Mondrian remain confronting. Red always makes an impression.

There is no way of avoiding The Red Dancer; the abundance of flaming red catches your eye. The greater part of the painting is dominated by the dancer’s radiant costume. The skirt, composed of various red and orange hues, forms a ragged diagonal across the canvas. Blotches and rough stripes of colour, painted in an irregular rhythmical pattern, give the impression of motion. Could these patterns represent the ruffles of an underskirt? The dancer’s leg, camouflaged in an orange stocking, is lifted to waist height. Possibly the red dancer is performing that popular music hall dance, the cancan. But this is pure guesswork; Van Dongen’s close up eliminates all the foot work and removes any recognizable background.

The top right section of the canvas is reserved for the dancer’s bare upper body; her face appears in profile. The contours of her face, neck and shoulders are clearly defined, contrasting strongly with the jagged edges of her voluminous skirt. She, as so many of Van Dongen’s women, wears heavy make-up. Her mouth is smudged with vibrant red lipstick, and the one visible eye is little more than a blob of dark paint with a green patch. Van Dongen’s ‘women’ often have a green tinted skin and green features daubed on their faces; in this painting, green smears embellish the hairline. Van Dongen, a Fauvist, is known for his bold use of colour. He also had a great fascination for that world-changing innovation, the electric light. He often invited models to his atelier, to specifically pose under harsh electrical bulbs, painting the shadows that emerged in various hues of green. This however does not explain the ragged green strip on the dancer’s white garter. Green and red are, of course, complementary colours and no doubt Van Dongen, inspired by Van Gogh and Matisse, exploited bold colours and sharp contrasts. There is another possible explanation. By placing a green mark brutally next to the red plane, Van Dongen dramatically draws the viewer’s attention to the dancer’s leg, highlighting the sexual implications of this provocative work.

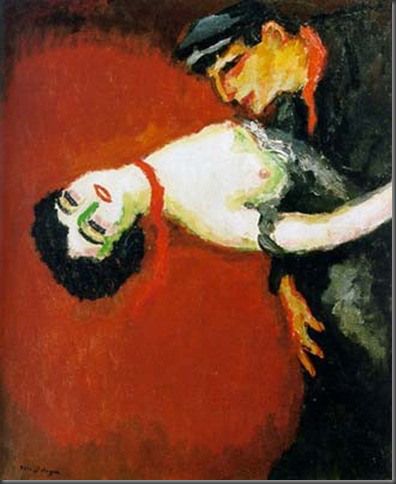

- Kees van Dongen – La Valse Chaloupée – 1906 – 54.6 x 46cm – Christie’s

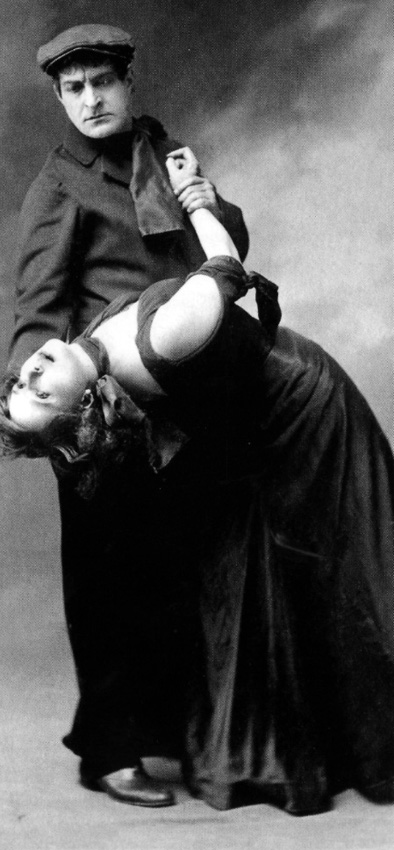

- Mistinguette and Max Dearly – La Valse Chaloupée

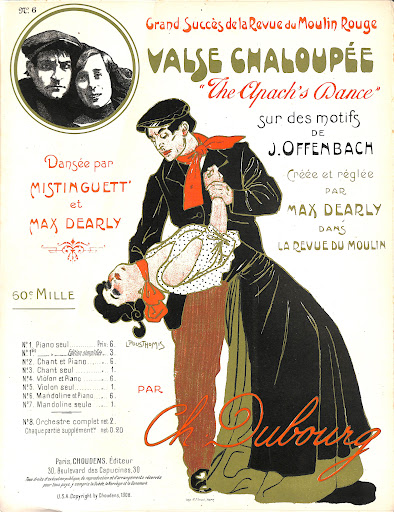

- Valse Chaloupée – music cover

Just as in The Red Dancer, Van Dongen has eliminated all that he considers superfluous in La Valse Chaloupée. The dance itself is not shown. Van Dongen has reduced the image to one characteristic pose; well-known throughout Paris from publicity photos and posters. The passionate couple portrayed here are the sensational entertainer, Mistinguette, and her famous partner, Max Dearly. The highly popular Valse Chaloupée (also called Apache Dance), is a rigorous dance imitating a physical struggle between a ruffian and street girl. Aggressive as this dance can be, the female dancer is not topless. In her memoirs, Mistinguette recalls that van Dongen adjusted her costume ‘putting my breasts in the air to make a better picture’. *

That ‘better picture’ shows the bare breasted Mistinguette intimately grasped in her partner’s arms. His hand, painted very roughly, is placed eagerly on her bottom, supporting her as she leans backwards. For the most part, he hovers in the shadow, with only his profile visibly illuminated. Van Dongen, never known to shun the lascivious, shows him leaning forward to embrace her exposed breast. Van Dongen uses bold colouring, placing this scene in a large circle of vivid red. Mistinguette’s pale body, illuminated by stage lighting, contrasts distinctly with the abundance of red. Her red neck scarf, on the contrary, that disturbingly divides the head and torso, forms a strange bridge between the opposing hues. Even more unorthodox, but typical of Van Dongen, is the greenish shading of the woman’s skin and, more specific, the dark green stripe on her face.

To be perfectly honest, the main colour of Oranjefeest is not actually red, but orange as the title suggests. However, the exuberance of colour and the vitality of the dancers is so irresistible that, I feel justified to include this high-spirited painting in this post. There is no way of escaping that clump of orange placed right in the centre of the painting. Neither can you miss the orange lantern that the jubilant woman is holding. A close look reveals, that not one, but, a group of women is intertwined forming an orange cluster. The woman in orange bloomers, who practically falls backwards, attracts the most immediate attention. She is obviously oblivious of the outside world, evidently drunk, and sings at the top of her voice. The artist, Jacobus van Looy, known for painting ordinary townsfolk, renders her in an uncomplimentary fashion; he illuminates a section of her face, accentuating her excessively open mouth and her explicit nose. At her side, not conspicuous at first sight, a second woman, just as merry, runs straight towards the viewer. Many more festive folk revels in the background, while some, including the fatigued woman on the outer right, are moving out of the frame.

The painting commemorates the festivities celebrating the seventieth birthday of the Dutch King, Willem III in 1887. Jacobus van Looy recounts that whilst roaming aimlessly through Amsterdam, late at night, the singing, the yelling, the dancing, the light of the street lanterns, the fireworks and above all the hodgepodge of orange made a great impression on him. Not, as you might expect, necessarily a pleasant impression. Van Looy made three different versions of this event. This scintillating painting, made two years after the celebrations, sharply evokes Van Looy’s vision of drunken women, orange cheeriness, crude yelling and the unrestrained pandemonium.

How dominant can a colour be? The painting of the revue dancer, Emmy Emerants, is saturated with a multitude of red and orange hues. Even the background has a reddish glow. Herman Bieling (1887-1964), a painter born in Rotterdam and founding member of an art federation called ‘De Branding’ has spaced this flamboyant dancer over the entire panel. She dominates the panel, her voluminous skirt extended to the outer edges. Her head-gear, an enormous array of feathers, is so large that parts had to be cropped. To make her even more striking, brightly lit stage lights are projected onto her face and costume. Beiling, was noted for his unique synthesis of cubism and expressionism. Interesting is that the background here is nondescript; the reddish brown shapes and forms intercept and mingle, fusing into an indistinguishable assemblage. Equally, interesting is the way Emerants moves along the stage; Bieling has only painted one leg. Is she walking, bowing, or perhaps landing from a jump? However fascinating it may be to speculate as to the artist’s intention, this question cannot distract the viewer from the overbearing impact of the vivid colour scheme.

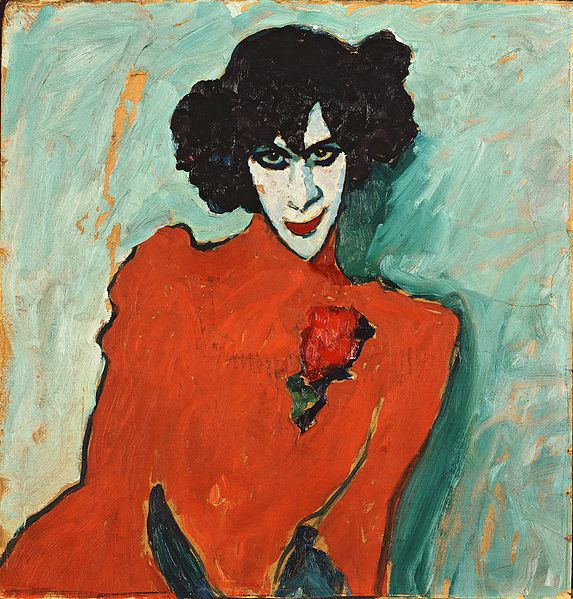

Alexej von Jawlensky – Portrait of Alexander Sakharoff – 1909 – Stäatische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munchen (click on image to enlarge)

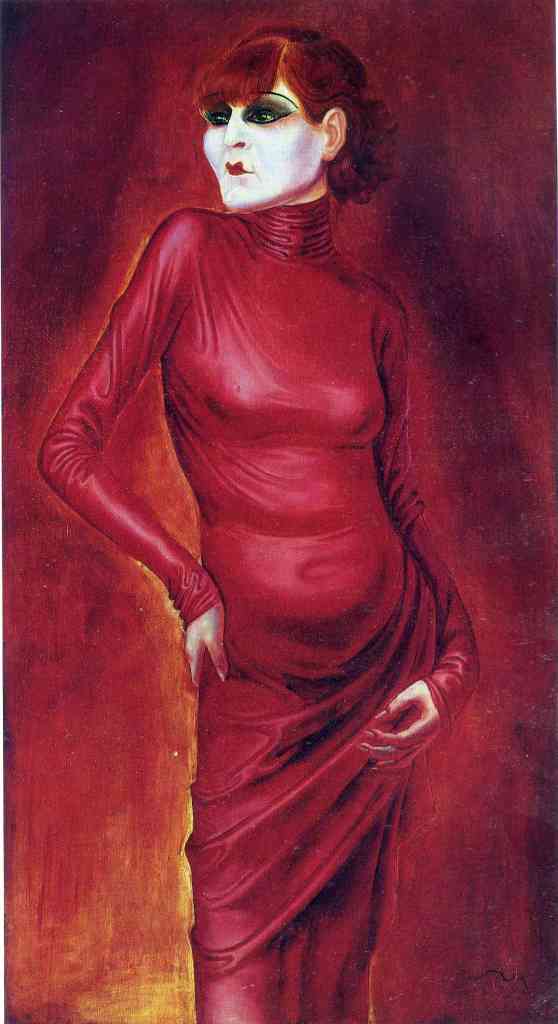

I cannot resist adding two paintings, by non-Dutch painters, where the use of the colour red is sensational. The German artist, Otto Dix created a vamp-like portrait of Anita Berber; her red hair and her red dress melt into the red background. The second stunning painting is a portrait of the expressionist dancer Alexander Sakharoff by the Russian artist, Alexei von Jawelensky (1909); an unrestrained use of complementary colours. The colour red cannot be ignored. Red demands attention.

* Memoires Mistinguette – Mmoires – Parisien Librt – entry for 14 November 1953