As a young man, the Dutch artist, Kees van Dongen travelled to Paris. He resided in Montmartre, living in a flat with a view of the Moulin de la Galette, the famous dance hall, from his rear window. The dance-halls, the circus, the cafés, the theatres all sparked Van Dongen’s imagination. His models were harlots, dancers, actresses and chansonnières, figures from the demi-monde. His work was bold, provocative and frequently controversial. Van Dongen, a Fauvist at the time, rendered his subjects in brilliant hues, executed in solid planes of colour, often painted with a heavy brushstroke.

Orientalism, especially that of the Arab world, was extremely popular in Paris in the early decades of the 20th century. High society dressed in exotic clothing, decorated their salons in vibrant oriental colour schemes, wore jewellery inspired by a Thousand and One Nights, complemented with perfumes as seductive as those worn by Schéhérazade. Art, music, and dance also embraced Orientalism. Kees van Dongen integrated his fascination for dancers with his curiosity of the Oriental; he collected several plaster replicas of oriental sculptures.

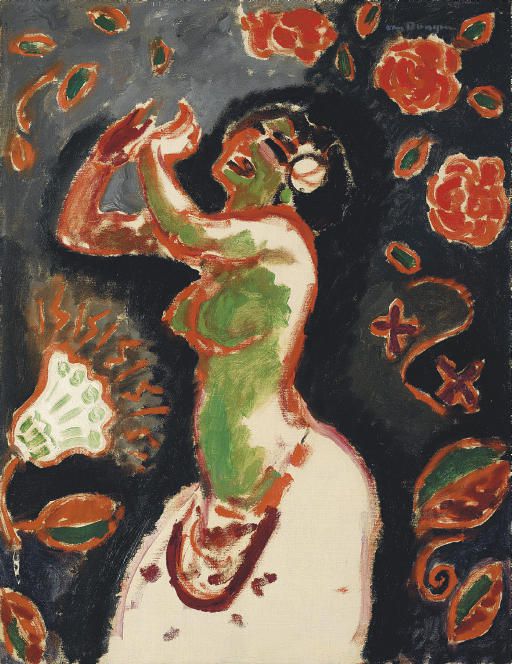

Oriental themes dominated Van Dongen’s work during his Fauvre period. Van Dongen spotted, the belly dancer, Anita, known as Anita la Bohémienne, dancing at one of the clubs in Place Pigalle; this distinctive gypsy dancer, teeming with desirability, inspirited the young artist, posing for more than a few paintings. The dark beauty Anita, shown in the painting below, is energetic, exhilarating, and unmistakably passionate. The belly dancer, come striptease artist, thrilled the demanding Parisian audience. Van Dongen’s, Anita, is the hallmark of sensuality, and placed in a setting of exotic flowers, the guise of fashionable Parisian Orientalism.

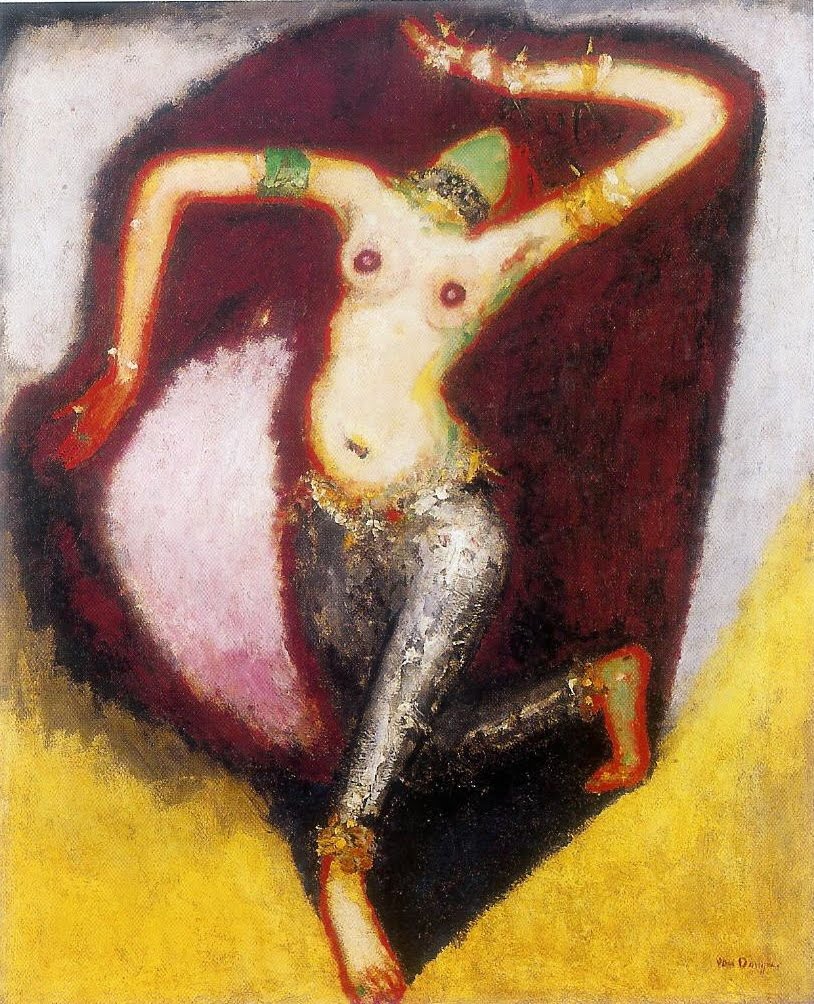

The show dancer, Anita is no less ravishing, when posing as the beautiful Fatima performing with her troupe, or when presenting herself as a provocative oriental dancer. Fatima, the performer, is an attractive dancer; she is long, slim and poses her agile body in a slight, undeniably suggestive, curve. Van Dongen has emphasized her alluring hips by placing three chains of beads, possibly coins, around her pelvis. Each subtle sway or shiver will cause her chains to jingle. The beautiful Fatima has raised her arms onto her forehead, enabling her veil to fall delicately over her arms and shoulders and all the way down her back. She gently covers her eyes, directing the viewer, without reservation, towards her amiable mouth and her conspicuous nostrils. That Van Dongen has concealed Fatima’s eyes is most unusual. In many of his female portraits, the woman’s eyes are highlighted; mostly dark and nearly always painted in an almond shape. The two women, seated on either side of Fatima, have broad dark eyes, as if marked with charcoal. The woman on the left has thick brown markings, under the two dark smears that represent her eyes.

Above : Anita en almée – 1908 – Christie’s 194.9 x 113.7 cm

A solitary eye gazes straight at the viewer in Anita en almée. The dancer, part of her face concealed by a long veil, beholds the onlooker inviting scrutiny of her lips, nipples, navel and her welcoming hips. The sultry Anita, a showgirl, shamelessly displays her breasts and more. Just above her red belt, Van Dongen further eroticizes the image, exposing Anita’s pubic hair. In the background, glaring at the viewer, there is a red architectural column; unmistakably a phallic symbol. Anita en almée, is blatantly sensual. And yet, even though this daring painting received criticism, and was found highly confronting, there prevails a serene and enticing beauty. This effect is achieved by Van Dongen’s masterly juxtaposition of enticing pink hues, vividly contrasting with the hushed blue background, together with the soft rendering of Anita’s skin enhanced by an intricate ornamented string skirt. Nothing about this dance is authentic. Van Dongen’s inspiration was derived from the professional dancing girls in cafés, in the music halls and from paintings by the famous Orientalists; Delacroix, Ingres and Gérôme. In fact, Van Dongen first travelled to Morocco in 1910; two years after painting Anita en almée.

There is little subtlety in La Danseuse Indienne. A topless beauty rushes towards the viewer with full physical force. She, the personification of decisiveness, is vigorous, sensual and astonishingly ravishing. Those nipples, rendered in an exaggerated red tint, cannot escape your attention. They, coloured in the same tint as the indistinguishable background, thrust forward, demanding attention. This semi-nude dancer, her face hidden from sight, with arms that are anatomically impossible, takes on a quasi-Indian dance pose. The contours of her torso, the deeply bent knees, the agile crossing of the legs, the positioning of the back foot, and her elongated hooked arms and upturned wrists all embody the Oriental look. However, she is definitely not the traditional Hindu dancer. Once again, Van Dongen had sought his inspiration in the Parisian nightlife; his muse, the gypsy Anita, was the model for this bold, compelling painting that understandably startled the Parisian art world.

Orientalism was the rage in Paris. In this city, where both the demi-monde and beau-monde were infatuated by the exotic, the unknown and the mysterious, The Ballets Russes, under the leadership of Serge Diaghilev, presented the ballet Cléopâtre. Fashionable theatre goers accustomed to fairy tale ballets, ballerinas dressed in tutus and conventional choreography were astounded by the overpowering extravaganza of colour, enticing costumes and the unprecedented choreography. The innovative choreographer, Michael Fokine, devised original, often unorthodox movements that were entirely appropriate to the Egyptian narrative. Cléopâtre was revolutionary; the triumph of the 1909 season. This exotic ballet followed the romantic work, Les Sylphides, a choreography abounding in ballerinas wearing long white tutus. As the final curtain opened, the elite Parisian audience was literally plunged into a world of brilliant, exotic colour. The Russian artist Léon Bakst had designed a vast Egyptian chamber, with scintillating orange, exciting pink, radiant red and luscious violet hues. The colours were intoxicating. The setting, suggesting an arousing, sweltering Oriental evening, left the Parisian audiences awestruck. This is what Kees van Dongen witnessed when he, visited Le Théâtre du Châtelet on a June evening in 1909.

The ballet Cléopâtre tells the tale of two lovers, Ta-Hor and Amoun. On seeing Cléopâtre, entering the temple grounds Amoun (performed by Michael Fokine), immediately falls in love with her. Cléopâtre agrees to spend the night with him, on condition that he, in return, drinks a phial of poison. He agrees, much to Ta-Hor’s distress. The next morning, she returns to the temple to find the body of her dead lover.

And that is the very moment Van Dongen captures. Ta-Hor, totally distraught, extends her arms dramatically outward, stretching her elongated neck as far back as possible. We cannot see the features of her face, but every gesture of her fragile body utters agony. Reclining languidly behind her is seductive Cléopâtre, impervious to Ta-Hor’s anguish.

54.2 x 65 cm

Anna Pavlova performed Ta-Hor & Ida Rubinstein performed Cléopâtre

Anna Pavlova, the leading ballerina of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes and Ida Rubinstein, an actress performing with the company, are unrecognizable. Van Dongen has painted his personal recollection, a souvenir, of the performance. It is clear that, besides the overwhelming dancers, Bakst’s astonishing colouration and the powerful impact of his colours reign supreme. Against a background of various shades of blue, Ta-Hor, is outlined in red and further sheathed in tints of yellowish-brown. Her pathetic presence figures prominently, barely fitting within the boundaries of the canvas. Even bolder colours embellish Cléopâtre, presumably slumbering on her chaise lounge. She too, is outlined in red; van Dongen emphasizes her sexuality with a well-defined markings. The Egyptian Queen, marginally rendered, yields to the artist’s unnatural, conspicuous colours; greens and yellows complement her bizarre green face. In the ballet performance, Cléopâtre first appears enclosed in a number of coloured veils. One by one, they are removed, to finally reveal Ida Rubinstein’s flimsily clothed, sensational body. Possibly van Dongen has incorporated this memory; colours, eroticism and Orientalism into his Souvenir.

From his earliest years van Dongen also illustrated books. In 1955 he revisited La Danseuse Indienne adapting the exciting painting as an illustration for La Danse de Morgane in Le livre de mille nuits et une nuit.

The dancer looks familiar. This seductive dancer, however, is so much slimmer than her 1907 counterpart; her torso is longer and her waist is now, exceptionally slender. Just as the dancer in La Danseuse Indienne, she rushes forward. Once again, her nipples, coloured intense red, lead the way. The dancer’s arms are unnaturally arched and angular. The flexed hands and wrist retain an ‘Indian touch’. Composition wise, the two works are similar; this dancer resides in a deep red frame contrasted against a dark blue background. New are the sparkles; the jewellery, the necklace, the waistline, the armlets all glitter. Morgane, the exotic, erotic beauty, practically bursts off the page.

Kees van Dongen loved dancing and watching dancers. From his earliest days, he painted irresistible night club dancers, acrobats, ordinary people enjoying a dance at the Moulin de la Galette, fashionable socialites and theatrical personalities. The poster he designed for Josephine Baker is stunning. Dance never failed to inspire Van Dongen throughout his long career.