The oriental dancer has captured the hearts and imagination of many artists. This striking dancer, whether from Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, Persia, or India to name but a few of her habitats, became a modish subject for paintings, ballets, films and literature. In the three previous posts I discussed a variety of dance images, made by Dutch artists, inspired by the orient. This post will focus on the celebrated oriental dancer, looking more specifically at 19th and 20th century Dutch artists.

Willem de Famars Testas (1834-1896) specialized in oriental scenes, having travelled to Egypt in 1858. Ten years later he joined a party, invited by the famous French orientalist Jean-Léon Gérôme, visiting Palestine, Syria and Egypt. On his return to the Netherlands he created Souvenir de Senouris dans le Fayoum, the dance scene shown below. This is an engaging image; musicians and a few locals are seen sitting on the left side and on the right, five non-Arab men. Three of them wear fashionable bowler hats and two others wear Eastern head wear. The artist has pictured himself sitting on a stool, holding a cigarette and wearing a keffiyeh, an Arab scarf. The Teylers Museum has a photograph showing Testas in high boots, a large gold ring on his left hand, wearing such headgear. The other men are, in all probability, Jean-Léon Gérôme, together with the artists of the touring group. This artistic expedition apparently travelled to Senouris, a village in the Faiyum oasis, and arranged to see traditional Egyptian dancing. Possibly this was a private performance since the artists/onlookers look totally relaxed in their front row seats; actually they appear to be the only guests present.

(click on image to expand)

Belly dancing conjures up visions of films, nightclubs and tourist shows, where dancers, barely clad, roll their hips, making sensuous undulations of the upper body whilst meandering suggestively around a spacious stage. Testas portrayed a very different dancer. Suggestive, most certainly, but this dancer, even though she is an entertainer, performs a more traditional dance. She moves within a limited space. Her dance is quite stationary; she can make a few small steps to all directions and turn around her axis. This dancer, accompanied by a number of musicians, has discarded her shoes. Her décolleté plunges down between her breasts, but her legs are enclosed by a floor-length decorative shirt. The emphasis of her dancing, so unlike the contemporary French can-can where dancers show their legs blatantly and throw them high into the air, is entirely on the pelvis and torso. With eyes cast down, this bejewelled dancer, propels her pelvis, twists and turns her hips and torso, moves her arms fluidly whilst accompanying herself with the clatter of castanets. As she dances the chimes hanging from her belt ring, accompanying the jingling sound of her necklace, her scarf and even her hair; all of which are draped with coins or other metallic pieces.

Western artists like Testas and the other well-known Dutch Orientalist, Marius Bauer, about whom I wrote extensively in the last post, must have been fascinated by the oriental dancer. How different to the European female dancer, a product of the Victorian era, dressed in a stylish gown accentuating a well-defined waist line concocted by tight-fitting corsets. These immaculately dressed ladies danced the waltz, the most fashionable dance at the time, keeping perfect time and restraining any undue movement of both hips and torso. The oriental dancer, in contrast, had no constraining corset, wore loose garments enabling her to dance freely. The oriental dancer is not restricted; she could improvise and move her body in ways that was beyond any dancer, including the charming ballerina, in 19th century Europe. Marius Bauer, known for his realistic rendering, embodies, in the images shown below, the charismatic allure and seductiveness of the beguiling oriental dancer.

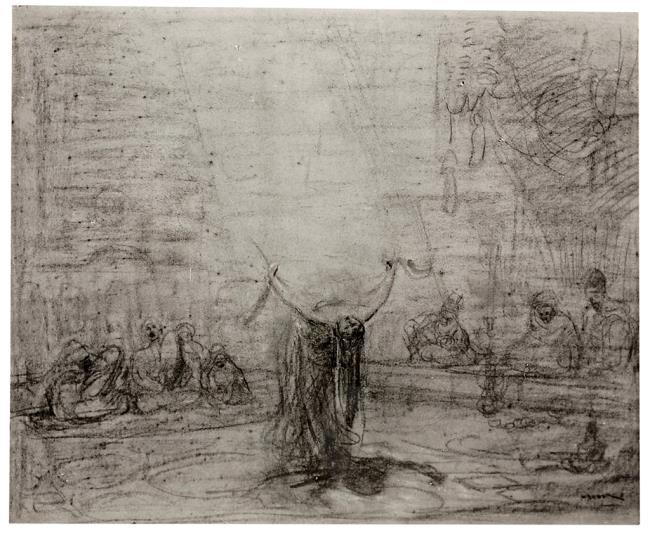

Left : Dancer – 1885-1918 – RKD

Right : Dancer – Pulchri Studio The Hague – reproduction 2017

(click on image to expand)

I suspect that the left image is set in a tent; the space appears to be circular. Bauer has sketched some hanging objects that vaguely resemble the three hanging lamps in Testas’ image. A group of musicians is seated on a carpet and on the opposite side of the dancer; three spectators are squatting on a low bench. The right image shows the spectators lounging on a similar bench. Could these images be of the same dancer? Has Bauer drawn the dancer from two different angles? In both cases we see the dancer from the back, once in the centre of a semi-circle surrounded by musicians and onlookers, and secondly, as the most pronounced figure towering over the three reposing men. Bauer has portrayed the women in very similar dress, shows them sweeping their scarves irresistibly, and pleasing their audience with tantalizing undulations of the pelvis and torso. No doubt, this dance requires nifty footwork, but this is hidden from the onlooker. All the attention is drawn elsewhere; the dancer in the left image thrusts her pelvis significantly forward moving into a ravishing back bend and the dancer on the right, rotates and swivels continually enticing her admirers. All these uninhibited dance movements, unquestionably, made a great impression on the Western artist; I can visualize Bauer sketching quickly, capturing, as he well could, the absolute essence of the performance.

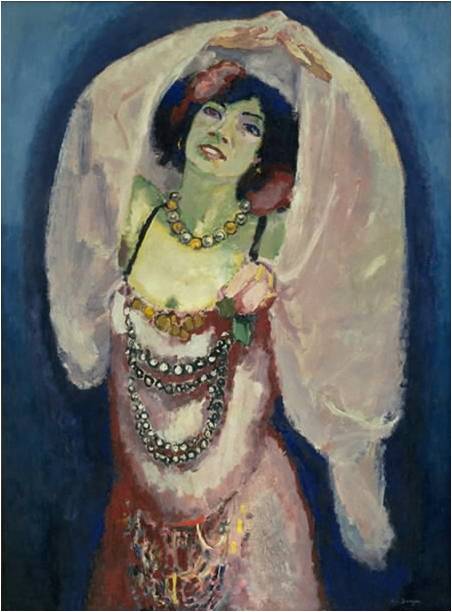

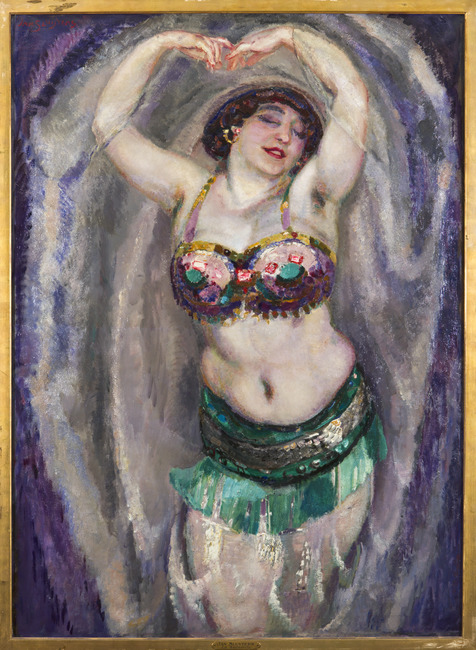

The new generation of painters approached the exotic dancer in a very different manner. Where Testas and Bauer gave a fairly realistic rendering of the dancer, the movements and the social surroundings, early 20th artists, Kees van Dongen and Jan Sluijters, painted the dancer as a performer, but were equally fascinated by the woman behind the dancer.

Right: Jan Sluijters – La Sulamite – c.1914 (model Greet van Cooten ) – RKD – private collection

(click on image to expand)

Anita la Bohémienne was a belly dancer working in Paris. The exiting gypsy dancer was, not only van Dongen’s muse, posing for numerous paintings, but also his one-time mistress. This half-portrait of Anita, beautifully adorned with jewels and flowers, highlights the dancer’s appeal and attractiveness. Even though we only see the upper part of Anita, you are aware of her arousing hip motions that she craftily combines with playful movements of her scarf.

Jan Sluijters painting La Sulamite is sensuality embodied. This scantily dressed woman, with only a diaphanous cloth to cover her legs, displaying her bare belly and wearing a glittering brassiere decorated with multicoloured stones, is entirely immersed in her inner world. She is an alluring woman, an exotic dancer who becomes more provocative with every roll of her hips, every shift of her torso. Is she seducing her lover, or is she so involved in her own physicality that she closes her eyes in ecstasy? Could Sluijters have been moved by The Song of Songs, the passionate love story in the Hebrew Bible, which inspired Emmanuel Chabrier to compose La Sulamite (1885) or was he enraptured by his model, Greet van Cooten, who happened to be his second wife?

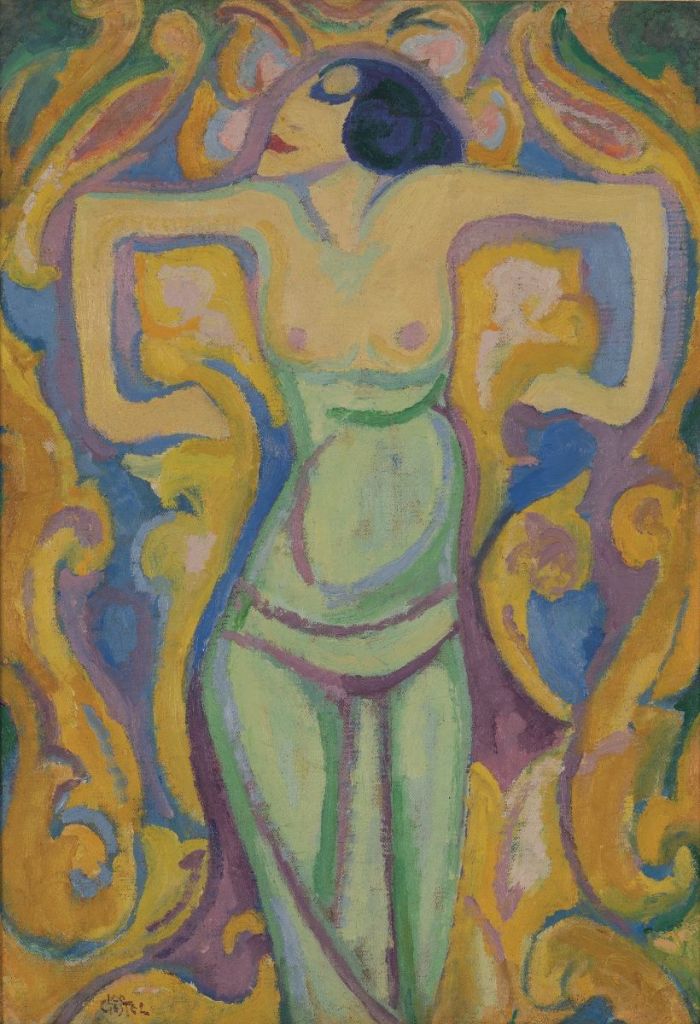

Danse Orientale c. 1912 – private collection, Singer Laren, The Netherlands

The prolific modern artist Leo Gestel (1881-1941) explored various styles including cubism, futurism, and fauvism. Among his dance images is this powerfully distinctive painting of an oriental dancer. Within a curvilinear background of orange, purples and radiant pink hues, a topless dancer emerges. The figure, just as the background, is painted in vivid colours; only the blueish-black hair and the dark mark suggesting the eyes differ from the artificial colour scheme. There is nothing commonplace about this painting. The dancer’s arms are anatomically impossible, and her shoulders practically merge into her inquisitive head. And yet, within this expressive unnaturalness, Gestel with his rough lines, irregular shapes and blobs of colour has captured the essential characteristics of an oriental dancer; sensuality, charisma, and temperament.

Kees Maks, who worked intermittently in Paris and in Amsterdam, loved theatrical entertainment. The fashionable nightlife, the circus, the dance halls, revues, cafés, and dancers all feature in his figurative art. Characteristic of his work is a strong contrast between light and dark, a rough brush stroke, and the varied textures.

(click on image to expand)

Maks’ love of the theatrical is immediately noticeable in his portrayal of an Arabian dancer. This dancer rivals Mata Hari, Maud Allen, and the many sensational Salomé interpreters with her translucent pantaloons, decorated brassiere and memorable smile, obviously aimed at some member of her audience. This is a trained dancer; she dances barefoot, stands high on the ball of the foot, simultaneously executing a technical ballet movement. In each hand she holds a castanet, accompanying the rhythm of the two musicians sitting on the bench behind her. Lounging on the bench is a yearning admirer. This displeases the woman sitting upright next to him; she directs her blasé glance straight towards the onlooker. Judging from the reflection in the mirror, this scene takes place in a café or night club, where the audience is, most likely, sitting, drinking and watching the show. There is nothing folkloric about this dancer. Contrary to the traditional dancer, where leg and footwork are of secondary importance, this professional performer flaunts her legs, lifting one leg flirtatiously to waist height.

Kees Maks revisited the Arabian Dancer, painting a smaller but very similar painting as his entry for a Salomé competition, promoting the 1953 motion picture Salomé, starring Rita Hayworth. In a previous post about Salomé, I discussed the entries by Jan Sluijters and Matthieu Wiegman.

(click on image to expand)

Similar as the two paintings are, there are, besides a disparity in size, a few important differences. The setting, a café with a mirrored wall, is familiar. The yearning man, comfortably leaning on the couch, is still present, but the glum woman, originally sitting next to him, has made way for a musical successor playing a drum. All the figures, including the woman playing a string instrument, have an oriental appearance. But more essentially, Kees Maks has altered the dancer; she now dances on ornamented slippers, her pantaloons are less transparent, and most strikingly, he has switched the position of the dancer’s legs and exchanged the castanets for a long flimsy scarf. Maks has morphed The Arabian Dancer into an eye-catching, seductive Salomé.