The whirling dervishes are mesmerizing. Tourists visiting Turkey flock to Konya, home of the Mevlevi, to experience the centuries old mystical whirling ritual. This ritual, now often seen as a popular tourist attraction, was originally and still is a religious celebration bound in spiritual symbolism. The dervishes, clad in white robes, best described as a long, wide pleated frock, start to whirl after an initial solemn introductory ceremony. The whirling itself symbolizes the celestial motions. With the left foot planted on the floor, the dervish swivels, crossing the right foot over the left, turning anti-clockwise; symbolizing the earth turning on its axis. With each revolution, the dervish displaces slightly to the right, moving in a circular fashion through the hall, symbolizing the earth’s rotation around the sun. The positioning of the arms is also symbolic. As the dervish starts to whirl, he raises his right palm upward, receiving the Divine Grace, whilst his left palm faces downwards to convey the received Grace towards the earth. Often the head inclines softly towards the right arm, and some dervishes even close their eyes. As the ritual proceeds, the dervish, chanting ‘Allah’ with on each revolution, frequently slides into a trance. The Sheikh, a wise, mostly an elder man, announces the end of each whirling session.

The French-Flemish artist, Jean-Baptiste Vanmour (1671-1737), accompanied the French Ambassador Charles de Ferriol to Constantinople in 1699. There, Ferriol commissioned Vanmour to paint a hundred paintings of the local people illustrating their work, dress, and customs. Ferriol left Constantinople in 1711 and on returning to France commissioned a series of a hundred engravings after the Vanmour paintings, as illustrations for an album entitled Recueil de cent estampes representant differentes nations du Levant, published in 1714. This widely acclaimed book, published in at least five languages, was reprinted a number of times with both black/white and coloured engravings. Vanmour’s paintings and the subsequent engravings became the archetype of Turkish culture; an inspiration for artists who readily copied and reproduced them.

Among the hundred paintings, is one of a dervish, a Mevlevi; his white robes contrast strongly against the dark, understated background. This whirling dervish, his arms placed in typical symbolic fashion, is serenely introspective as he would be during a Mevlevi ritual. Vanmour, and the artists employed in his workshop, carefully rendered every detail, from the placement of the feet to the specific positioning of the fingers of the right hand. The engraving (below left), from Recueil de cent estampes, is very similar to the original painting, though, the designer has added an appealing background of pilasters, a facade which is slightly flawed, windows and even a glimpse of a forest. The immense popularity of Recueil ensured Vanmour’s fame; his influence spread afar. The engraving, below right, is the work of the famous French born master engraver, Bernard Picart, who lived and worked in Amsterdam. This reproduction and the many others based on Vanmour’s images illustrate the celebrated study of world religions named, Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde, published between 1723 and 1743. Picart engravings show images of people from all corners of the world, but, he himself, never travelled outside of Europe.

Interesting is that Picart’s image, though very similar to the Vanmour image, has a few subtle differences. Apart from the obvious, that the image is mirrored and that the architectural design is marginally different, the most important distinction is the facial expression and sensitivity of the dervish. Picart’s dervish is inward-looking, even meditative, yet, I feel, fails, in comparison, to achieve the intense inner contemplation of Vanmour’s painting.

b) Bernard Picart – Dervish – Cérémonie et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde – 1723-1743 (click on image to enlarge)

The Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, houses a large collection of work by Jean-Baptiste Vanmour, including the ‘Whirling Dervishes’ painted between 1720 and 1737. Within the walls of the tekke, the Mevlevi loge, guests* watch the dervishes performing the Sema ceremony; a group of musicians is standing on the balcony. Contrary to the white attire, so well-known from the tourist brochures, these Mevlevi wear robes of autumn greens, red, beige and ochre. Vanmour, it appears, has painted the beginning of the ceremony; some dervishes are still walking slowly towards the Sheikh, to pay their respect, before they start whirling. Other dervishes are whirling, but as yet have not reached a state of inner meditation.

One of the best known images of whirling dervishes is an early 18th century image originally designed by Jean-Baptiste Vanmour for Ferriol’s famous volumes Recueil de cent estampes representant differentes nations du Levant. Shortly after, a very similar image, this time attributed to Bernard Picart, who was not in the habit of citing his sources, illustrated Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde. His pupil Jacob Folkema (1692-1767) is named as the engraver. This familiar engraving would be reproduced time and again throughout the century as well as an inspiration for other engraving and drawings by foreign artists illustrating travelogues, fashion or other books.

Inside the beautiful, though modestly decorated loge, Vanmour presents a large group of dervishes, quietly immersed in mediation. Despite their uniformity, the long gowns, the bare feet, the long cylinder shaped hats (sikke), their faces and expression remain markedly individual. On the right, three dervishes, with their arms extended outward and upwards, are in a state of deep concentration. The front dervish, his head inclined, and his palms turned towards his chest, is utterly absorbed in internal thought. The two dervishes, with their backs to the onlooker, one prone and the other kneeling down, may be in prayer of perhaps overcome by the continual turning. The dervishes are accompanied by a small group of chanters/musicians, seated on a high balcony, while behind the railing guests* are watching the ceremony. The entire sphere is one of inner contemplation; the dervishes achieving the highest form of spirituality during this repetitive ritual.

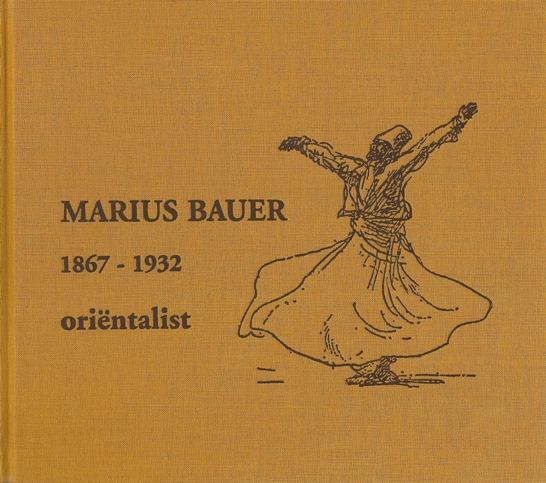

Fast forward to the second half of the 19th century. The Dutch painter, Marius Bauer (1867-1932) was fascinated by the east. He first travelled to Constantinople in 1888 and from that moment on, the main body of his work was inspired by the Orient. He was an avid traveller, travelling amongst many other countries to Morocco, Algeria, Egypt, Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and the Dutch East Indies, sketching palaces, kasbahs, emirs, markets, dancers, dervishes and everyday scenes. Back in the Netherlands these sketches and the photographs he purchased on his journeys, became the starting point for his paintings, etchings, and lithographs.

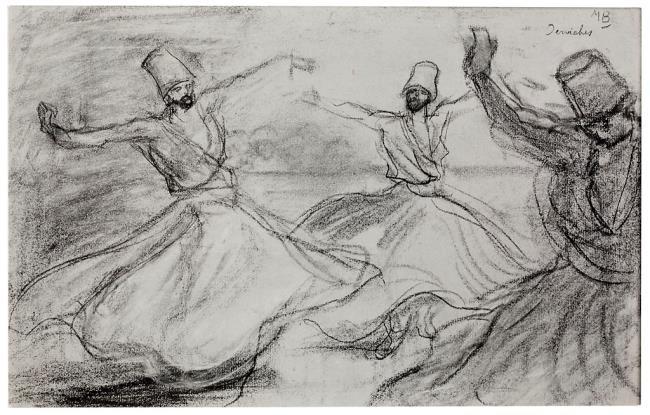

This sketch, with the name dervishes, handwritten in pencil, just under the monogram MB, is so realistic that you can practically see the dervishes actually turning. Each dervish is unique. The continual turning has transported the man, on the right, to a state of ecstasy. The other two dervishes are turning incessantly. Though a mere sketch, Bauer, through a clever play of dark and lighter pencil lines, intensified with strokes of chalk, suggest that the robes are genuinely spinning. In the background, little more than a shadow, guests* are watching the ceremony.

b) Marius Bauer – Dancing Dervish – private collection – watercolour on paper – Dolf van Omme

(click on image to enlarge)

The above impressionistic images are both entitled Dancing Dervishes; perhaps titles given by Bauer, but just as likely titles chosen by art dealers. These titles are, however, an understandable choice because both works are primarily about dancing and less about the ritualistic aspect of the Mevlevi Sema ceremony. The dancing, the turning, and Bauer’s uncanny ability to show movement captures the imagination. As in the earlier sketch, the voluminous whirling skirt immediately draws attention; the figures truly appear to dance in a circular motion. The figures at the back, more prominent in the yellow tinted painting, appear calmer; only their whirling skirts reveal that they are also rotating.

b) Dervish as book cover

(click on image to enlarge)

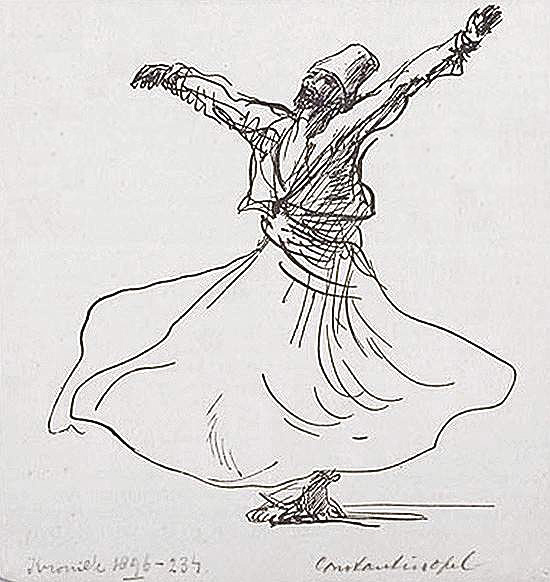

In 1896 a magazine, called The Chronicle (De Kroniek), published Bauer’s account of his recent trip to Constantinople. Bauer added his own illustrations. One illustration, that of a whirling dervish, has become so associated with Bauer that it often appears on a book cover, or as a flyer or as an image on a billboard announcing an upcoming exhibition. No wonder. This simple line drawing, emphasizing the wide sweeping skirt, the ecstatic arm gestures and the dervish’s rotary movement, all express the exoticness of the eastern world. Bauer never lost his fascination for the strange, the foreign or the exotic. His dance images are so convincing that it feels as if the dancers are genuinely moving. Marius Bauer, the orientalist, evoked the romanticism of a distant world.

* I use the word guests and not audience, because, even though the whirling dervishes have become a tourist attraction, the entire ceremony, to this very day, is not a dance performance but a contemplative religious ceremony.