Amsterdam, in the 17th century, was the hub of international trade. Grand tall-ships, from the Dutch East India Company, docked regularly at the harbour, laden with exotic merchandise, silks, spices, porcelain, textiles and other precious commodities. Amsterdam was a bustling city where merchants, legates and agents from many distant and mysterious countries were welcome, frequenting all aspects of city life. Amsterdam was a melting pot; different cultures fused with the traditional city life. The streets of Amsterdam were touched by the exotic; the aroma of spices, shops selling white and blue Chinese porcelain, ladies meandering in gowns made of fine silks or merchants wearing a turban. Many aspects of daily life absorbed elements of eastern culture. Art did the same. Rembrandt (1606-1669), as other artists of his time, painted portraits of a western gentleman clad in eastern apparel.

An interesting example of how the exotic influenced Dutch art, is a painting by Rembrandt’s teacher, Pieter Lastman (1583-1633). It tells the Old Testament tale of Jephthah, who vowed to God, that if he defeated the Ammonites he would sacrifice the first person he saw on returning to home. The painting shows the moment of Jephthah’s victorious return to see his only daughter, greeting him with ‘hand drums and dancing’. Jephthah wearing a magnificent turban and in every aspect an oriental ruler, is mounted high on his horse. Paradoxically, his daughter and her companions are fashionably dressed, in typically western fashion. Lastman casually fuses elements from both the East and the West, composing a curious, colourful medley of styles.

Lastman’s portrayal of the youthful dancing daughter is, from my point of view, not exceptionally convincing. She, nor her companion, dance joyfully at her father’s triumphal return. Other artists, Hieronymus Francken III , Pieter Lisaert IV (attributed to) and Peter van Lint, though not all inspired by the East, show Jephthah’s daughter dancing with much greater exuberance.

Jean-Baptiste Vanmour (Van Mour) who worked and lived in Constantinople for thirty-seven years, and his contemporary Bernard Picart, who never travelled outside of Europe, are both known for their extensive array of exotic images.

b) Bernard Picart – Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde – BNF

(click on image to enlarge)

Jean-Baptiste Vanmour (1671-1737), born in the Spanish Netherlands, left for Turkey in 1699 and remained in Constantinople until his demise, painting local people, portraits of court personages and, as an influential painter, having access to court functions and ceremonies, painted life at court during the reign of Sultan Ahmed III. His paintings, many of which are housed in the Rijksmuseum, are priceless in that they give an unforeseen insight into the life, customs and fashion of the early 18th century Ottoman Empire. His large oeuvre features a harem dance, a wedding dance, festive dances, religious dances and an image of a Greek folk dance, a khorra, which, so the Rijksmuseum information tells us, was performed in the countryside outside Constantinople by Greek men and women. Each dancer, dressed in opulent attire complemented with splendid headwear, stands imposingly tall, displaying their elegance. Vanmour has taken care to meticulously outline the footwork; the dancers have bent their right leg at calf height in combination with a flexed ankle. On a green patch in the background, a second row of five dancers, only men if I am not mistaken, dance with similar exactitude. They, unlike the front line, wear typical Greek national dress, the fustanella, a knee-length skirt worn on ceremonial occasions. Here, too, Vanmour has paid attention to detail. All the dancers have raised their right foot, in anticipation of the next step, whilst holding each other’s hands as if they are dancing the Chamiko (also written Tsamiko), the Greek national dance.

(click on image to enlarge)

Vanmour’s contemporary, Bernard Picart, a French engraver who lived and worked in Amsterdam, together with Dutch bookseller and publisher Jean-Frédéric Bernard collaborated on Cérémonies et coutumes religieuses de tous les peuples du monde. Published between 1723 and 1743, these originally seven volumes, a study of all the religions of the world, were illustrated with 266 plates by Bernard Picart.

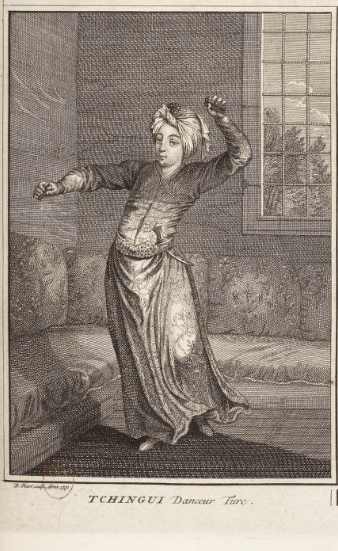

That Picart never travelled outside of Europe raises the question of how he could possibly illustrate these extensive volumes that cover ceremonies and customs from the Americas, to Africa, to the Orient and most other parts of the world. He was certainly never present at most, if any, of the ceremonies and feasts he illustrated. Picart, who incidentally furnished many other book illustrations, including various dance images, did not cite the source of his Cérémonies illustrations. A master engraver and illustrator, Picart was inspired by travelogues, frequently basing his engravings on existing illustrations. The two images of the Turkish dancer, shown above, are a case in point. The dance figure on the oil painting by, or, after Jean-Baptiste Vanmour appears, in reverse, as an engraving in Bernard Picart’s volume. I must stress that, contrary to today, it was neither unusual nor inappropriate for artists to borrow or to ‘recycle’ each other’s work.

a – Turkish dancer

b – Whirling Dervish

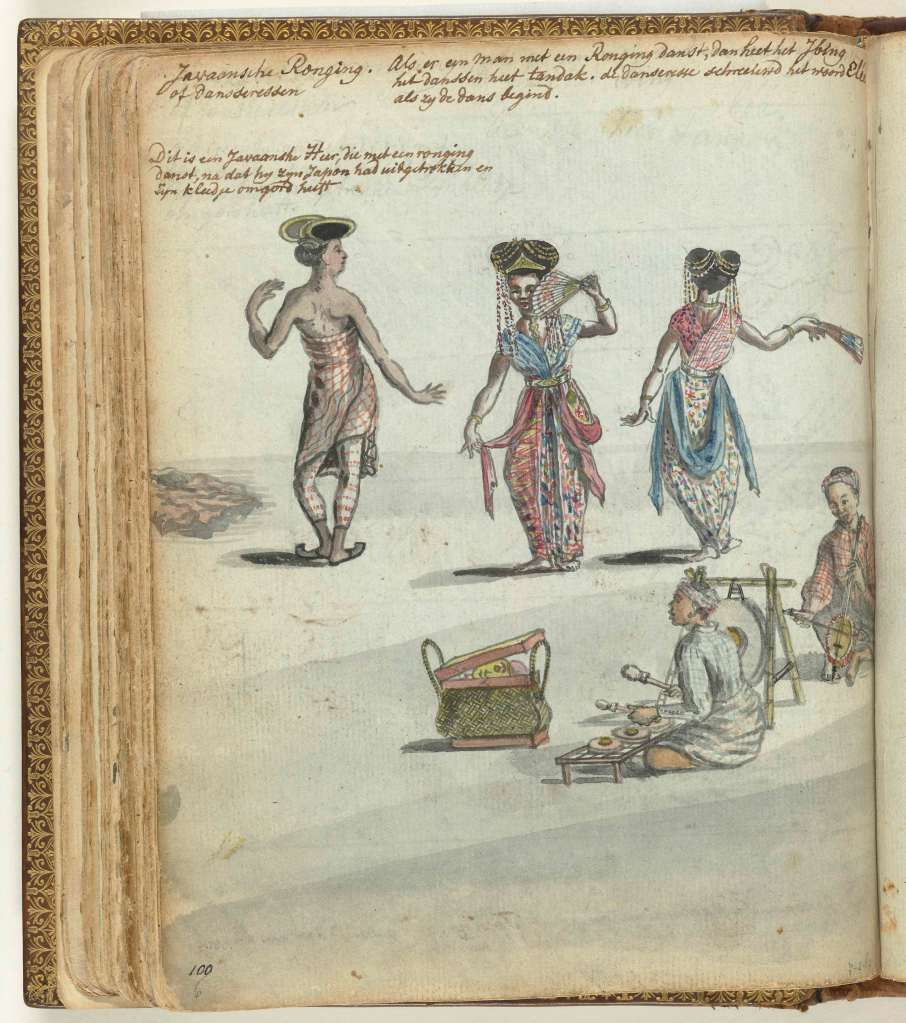

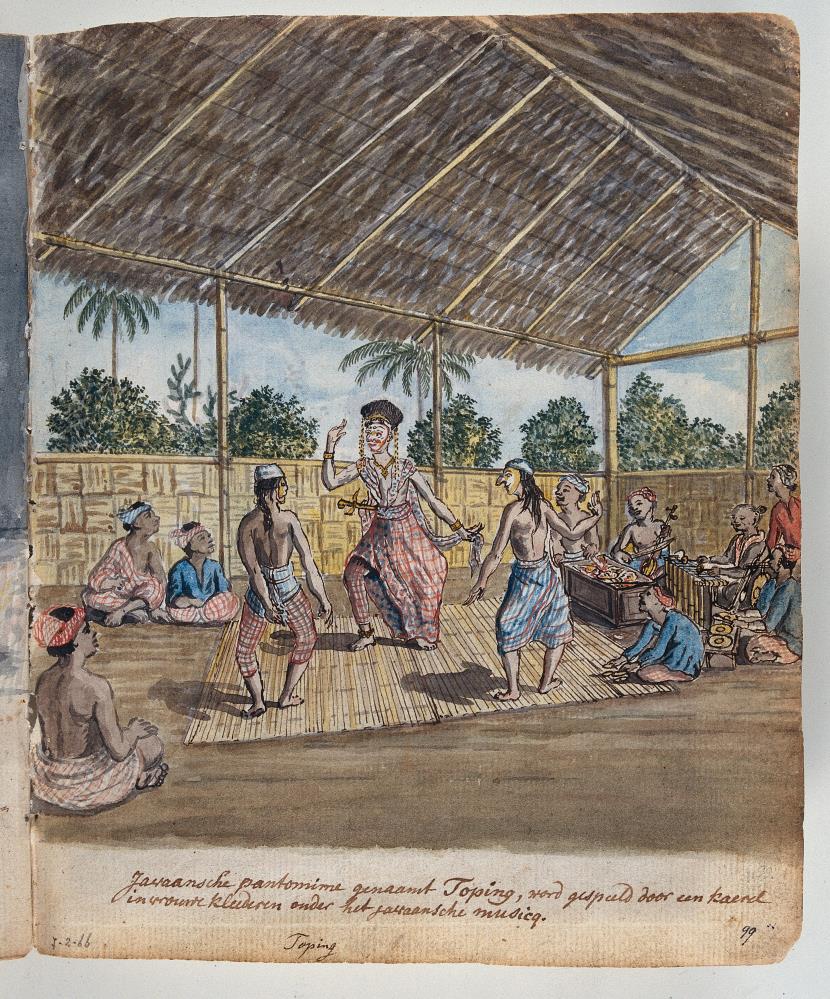

For two centuries, six hundred water-colours and sketches drawn by a Lutheran minister, lay undiscovered, treasured in a private collection. The minister, Jan Brandes (1743-1808) was stationed in Batavia, the headquarters of the Dutch East Indian Company in Asia. Brandes travelled for nine years through Java, Ceylon and South Africa. On returning to Europe he settled in Sweden where his large collection of drawings remained, out of view, until 1985 when the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam acquired the collection. The drawings present a hitherto undocumented picture of, amongst other places, Batavia. Jan Brandes had an amazing eye for detail. Besides images of official scenes, Brandes documented episodes of village life and drew a wonderful collection of exotic birds. Below are just two of his dance images; Brandes, here as he does in many of his drawings, has added some notes offering additional information.

a – Javanese dancers – 1779

b – Javanese pantomine Toping – 1779-85

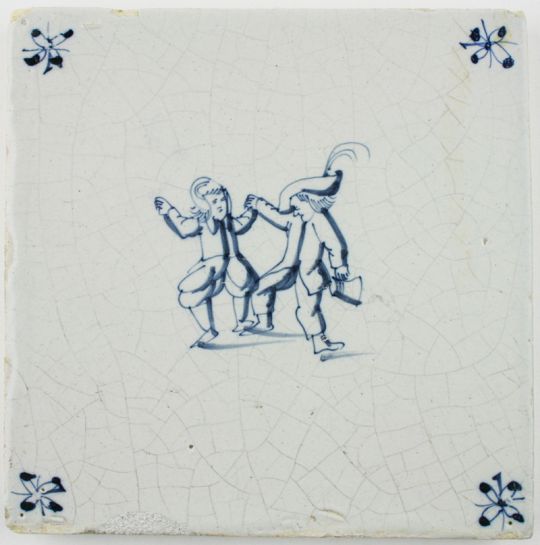

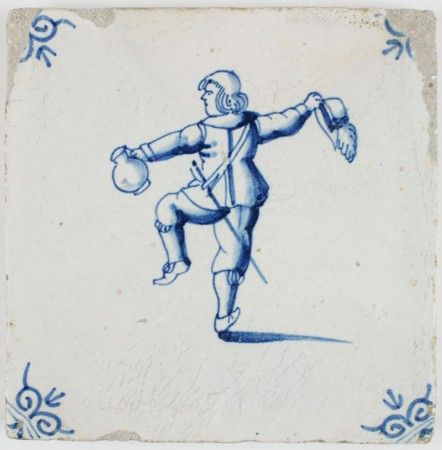

In the 17th century, war in China interrupted the production and exportation of Chinese porcelain. The potters in Delft, filling the void, developed an earthenware imitation of Chinese porcelain. At first Chinese motives and decorations prevailed, but soon the Delft pottery painters designed images of Dutch traditional scenes. Early tiles feature folk scenes; drinking scenes, children playing, feasts and of course peasants dancing.

b) a dancing couple – 17th c.

c) soldier drinking and dancing – c. 1660

(click on image to enlarge)

A Delft Blue violin, decorated by an anonymous artist, presents an image of wealthy, upper class citizens dancing, drinking and conversing in what appears to be a hall or tavern. Two musicians, one playing a violin and the other a double bass, stand on a platform just above the waist of the violin. This violin, which was never intended to be played on, fuses well -mannered figures, presumably from the Dutch Republic in a genteel, little adventurous dance on Delft earthenware inspired by Chinese porcelain.

Equally stunning is the panel ‘The Dancing Lesson‘ by Willem van der Koet originally made for The Galvão Mexia Palace in Lisbon. This large wall decoration, 170 x 400 cm, displays a dancing master teaching a handsomely dressed couple while other aristocrats enjoy the music, dancing and sunshine. All takes place on an extended patio placed in a woodland setting under a bright, though, lightly clouded sky. The dance master, with violin in hand, is teaching the gracious couple a fashionable court dance; perhaps a passepied, a gavotte or a minuet. The dancers are the epitome of refinement. The artist has obviously taken care to accurately illustrate the gentleman’s footwork, the placement of the couple’s hands, to indicate how an elite lady should daintily hold her skirt, and even draws attention to the correct carriage of a tricorn hat.

From the second half of the 17th century, Dutch ceramic masters, known for their technological and artistic know how, received commissions from Portugal, introducing Portugal to the blue and white Delft tiles. The workshops of Jan van Oort and Willem van der Kloet, themselves influenced by the Chinese porcelain makers, created large tile panels, as ‘The Dancing Lesson’ for their rich Portuguese clients.

History has a wonderful way of rejuvenating. A reproduction of Willem van der Kloet’s early 18th century image now decorates the VIP Hall of the Casa de Música, an ultra modern concert hall in Porto designed by the pre-eminent Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas.

The circle is round; the 17th century Chinese porcelain, imitated by Dutch masters, is commissioned by rich Portuguese patrons in the early 18th century. The Dutch master, Willem van der Kloet, designed a panel with an impressive aristocratic dance scene. Centuries later, this same design, but now re-created by Portuguese artists, forms a magnificent focal point in the breathtaking 21st century concert hall designed by the world renowned Dutch architect, Rem Koolhaas.