19th century Paris. Orientalism is booming. The paintings of Eugène Delacriox and Jean-Léon Gérôme introduce Paris to the mysterious and fascinating world of the exotic dancer. This unconventional woman, playfully navigating her veils, in turn concealing then revealing her body, captures the imagination of society and the arts. Interest in Salome is rekindled. In 1864, Stéphane Mallarmé, the prominent Symbolist poet, writes the dramatic poem Hérodiade. Gustave Moreau, the Symbolist artist exhibits two astonishing paintings of Salome in the 1876 Paris Salon. More than a half million people flocked to see Salome dancing before Herod and The Apparition. The following year Gustave Flaubert published a short story about Salome entitled ‘Heriodias’ and not long after, the protagonist Des Esseintes in Karel Joris Huysman’s novel Against the Grain, expresses his categorical obsession with Moreau’s Salome paintings. Salome becomes the embodiment of the Orient. In this realm of Orientalism the Irish author Oscar Wilde writes, in French, a play groping into the psyche of Salome (1891). Nineteenth century art and literature had converted Salome from a young, perhaps naive, dancer to a provocative Oriental beauty. Oscar Wilde thenceforth transforms her into a femme-fatale; a woman of flesh and blood. And Wilde by means of a simple stage direction, nearly two thousand years after Herod’s perverse banquet, bestows on Salome, the dance of the seven veils.

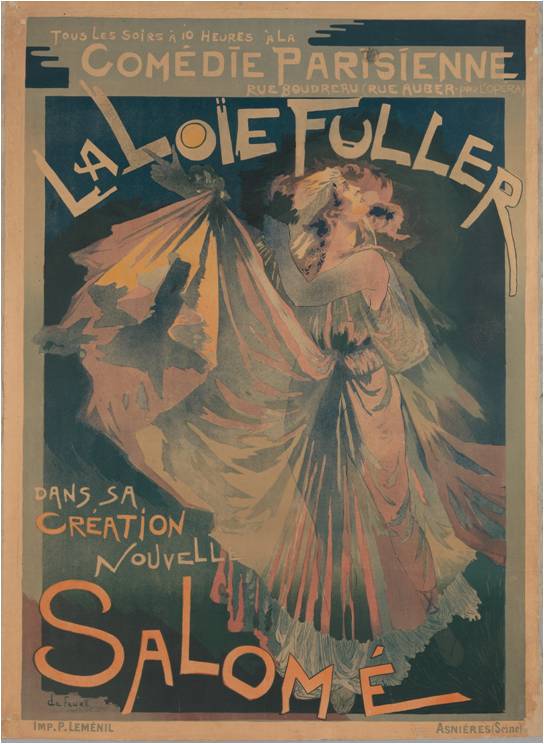

Oscar Wilde’s Salomé was first published in Paris, 1893. A year later it was published in England; Aubrey Beardsley (1872-1898) created the illustrations. The play premiered in Paris, 1896 and that was immediately the one and only performance. It would take months before Salomé saw the Parisian stage again. Later performances followed in Germany and the United States. Salomé was banned on the legitimate English stage until 1931.

By the turn of the century the notoriously seductive temptress had become a rage. Salome-mania turned up everywhere; in fashion, in dance, in art, in music and a little later in the cinema. Richard Strauss’s operatic adaption of the play, premiered in 1905 with a dance of seven veils lasting some seven minutes, even overshadowed Wilde’s stage production. Artists of both sides of the Atlantic were mesmerized. You only need to Google ‘Salome dancing’ to find many paintings, ranging from Salome dancing with a tambourine to the most erotically villainous woman moving sensually in Herod’s presence.

If I were to be asked to this give a title to the above painting, it would be as Salomé, the triumphal. How ecstatically Salome dances above the hallowed head of Jokanaan (Wilde’s name for John the Baptist). Her body, except for her bare breast, neck and head, is covered with undefined green veils, trimmed with a thin red border. Is this the green of jealousy? Wilde’s Salome craved for Jokanaan, and was prepared to go to any limit to achieve her goal.

The artist Harmen Meurs, inspired by the Fauvism, contrasts the colours forcefully. The head and torso, touched by light, stand out against the green curvilinear veils that float over the canvas. Salome’s head, poised upwards in venomous exultation continues the circular pathway in this, to my mind, overpowering painting.

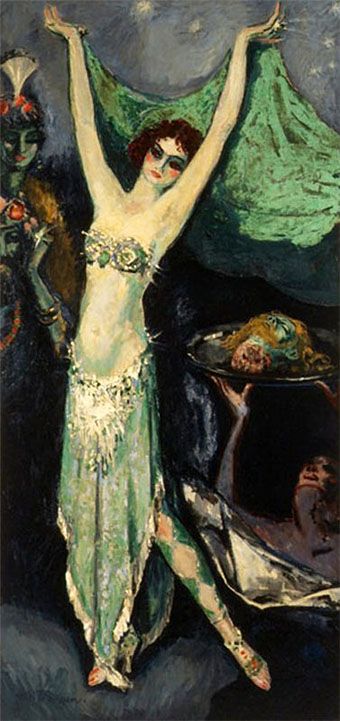

Kees van Dongen, a Dutch painter, working in Paris exhibited his sensational work with the Fauvres. He was obsessed by women, drawing his inspiration from the Parisian nightclubs, dancers, acrobats and nudes. Later he diverted his attention to painting portraits of Parisian society. The painting of Salome, shown above, in contrast to Herman Meurs’s intense personal interpretation, is, in actual fact, a portrait of the celebrated opera singer Geneviève Vix, in the role of Salome. The narrative is clear; Salome is victorious, the head of Jokanaan, lying on a platter, is raised gruesomely by the executioner.

Van Dongen’s figure has all the attributes one would expect of a fin du siècle Salome; nudity, veils, a brassiere embellished with jewels and a skirt laden with ornaments. She is long, slender and undeniably sensual as she raises her arms to highlight her breasts and to expose the fine contours of her tummy. And, from under her skirt emerges, quite deviously, a leg decorated with precious gems. Van Dongen, as Meurs, predominately uses greens; one shade of green for the skirt, another for the veil, a greenish tint for the woman standing just behind Salome (would this be Herodius?) and a vile green for the severed head of her would-be lover. The portrait of Geneviève Vix, as Salome, looks very similar to two of the most famous, of the many, Salome dancers, the Canadian Maud Allan and Dutch, Mata Hari.

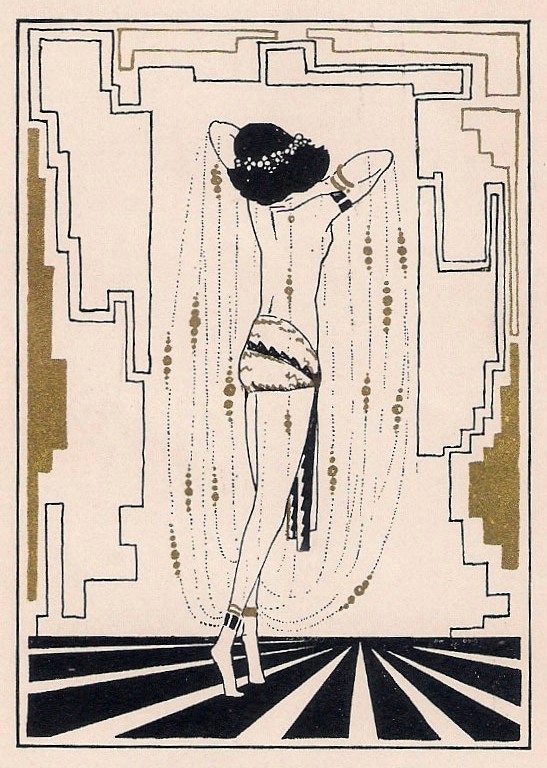

The controversial English illustrator Aubrey Beardsley designed a series of full page illustrations and a cover design for the 1893 English edition of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé. Each and every one of his illustrations is daring, a combination of the erotic, the grotesque and the decadent. Inspired by Japanese Art and the Art Nouveau, the illustrations are drawn in well-defined lines with stark, dramatic black and white shapes. Although Oscar Wilde’s Salomé was translated into Dutch as early as 1893, the publisher deemed it prudent not to use Beardsley’s ostensibly offensive illustrations. A 1920 publication of Salomé contains an illustration by Frits van Alphen that undeniably alluded to Beardsley’s unique style. The illustration, less blatant and not overtly erotic, displays the back view of a tall, slender female, barely clothed, enclosed in a diaphanous veil that is caressing her uplifted head. Just as Beardsley, this gracefully suggestive Salome is set in an empty white space with complimentary black planes. This solitary figure is surrounded by black pen lines, of varying lengths, that form a non-symmetrical frame. And to this, van Alphen adds a touch of his own; gold tinted geometric shapes and lines.

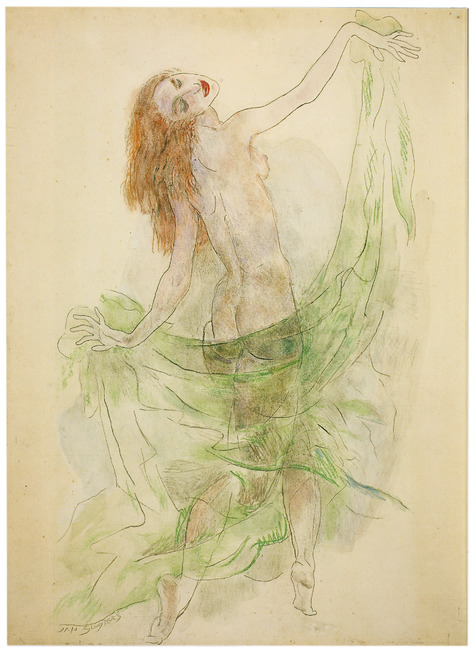

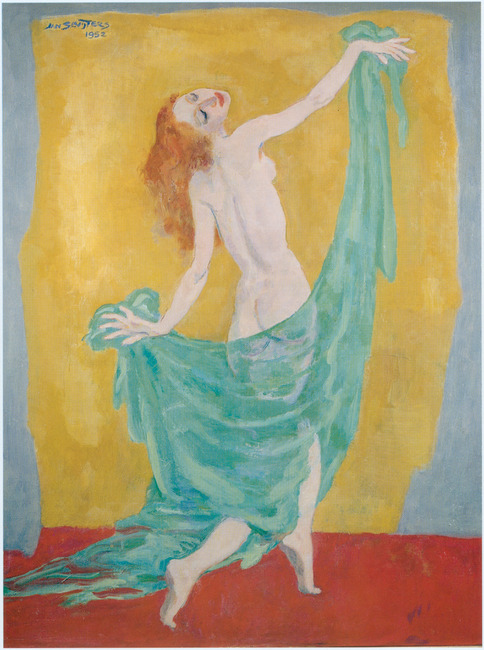

Dance and dancers have always fascinated the Dutch painter Jan Sluijters (1881-1957). Early in his career Sluijters painted a number of Spanish dancers, later he turned to social dancing and in the 1920s, his interest in dance was revived by the German expressionist dancer Gertrud Leistikov, who had settled in the Netherlands. Sluijters painted Leistikov many times. The painting shown on the right, was the artist’s entry for a contest held to promote the 1953 film Salomé, with Rita Hayworth in the title role. Sluijters’s Salome is a gracious, delicately proportioned young woman. The turquoise diaphanous veil floats over her legs just showing the gentle rounding of her derrière. This Salome is a captivating dancer displaying none of the decadent traits of the infamous Salome. This painting may have a predecessor. There is some doubt as to the original date of the Salome drawing on the left. The RKD (Netherlands Institute for Art History) suggest that this drawing could be dated as early as 1920, and if so, Gertrud Leistikov would most likely have been the artist’s inspiration.

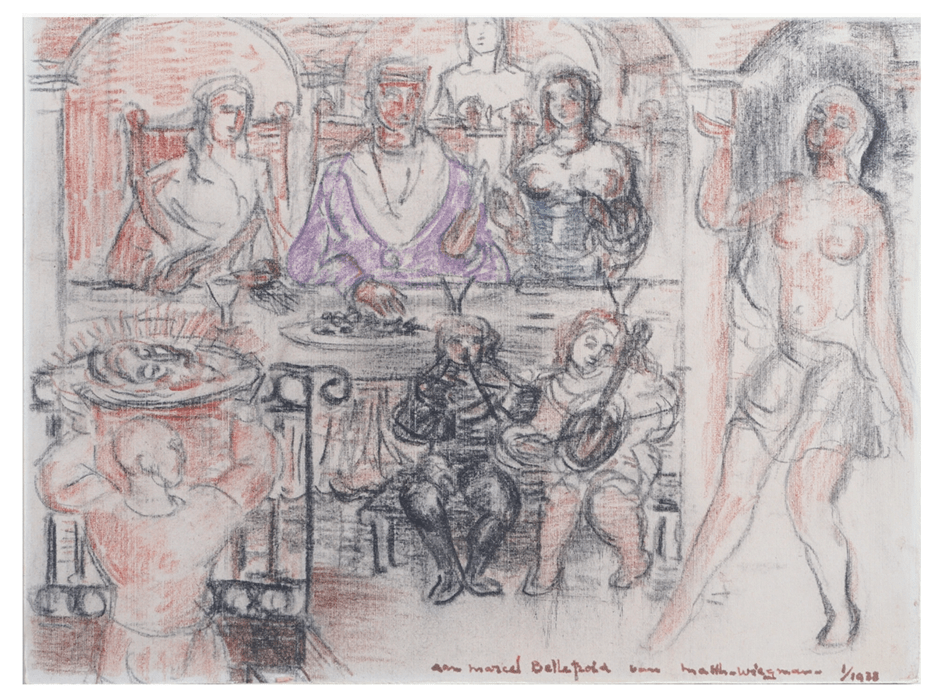

The Bergen School, an art colony situated in the Dutch town of Bergen, is known for its expressionistic style, often combined with cubist elements painted in relatively dark tints. Matthieu Wiegman, member of the Bergen School, created two versions of the Salome story. The first, a small work (21 cm x 28 cm) appeared in 1938. Years later he completed a large panel (240 cm x 300 cm) using approximately the same composition as the 1938 version, but now stylistically and colour-wise typical of the Bergen School.

- Matthieu Wiegman – Dance of Salome – 1952 (240cm x 300cm) – Rodi, Bergen in het nieuws

- Matthieu Wiegman – Dance of Salome – 1938 (21cm x 28cm) – Mutual Art

The first illustration shows a motionless, nude Salome, holding a veil. She is about to perform for Herod. She stands, almost as if pausing near a stage wing, waiting for her cue. Wiegman gives no indication as to her movements. Her static pose and the stiffly flexed hands fail to evoke any sensuality. In the background a stern looking trio, Herod, Herodius and a guest, sit rigidly. The scene is recognizable yet unrealistic. The flat cardboard figures with their immobile faces render the sphere aloof and highly unsympathetic. Only the musicians show a glimmer of animation. All the figures, including the composed Salome, are sharply defined by a thin black outline. Is this supposed to be an entertaining banquet? Apparently Herod must have enjoyed Salome’s performance; the severed head of John the Baptist, lying on a platter, is being carried up the stairs.

The second illustration, a small drawing, has basically the same composition, be it in reverse, as the larger work. The figures, of this earlier composition, however, are less flat, more animated and each personage has an individual expression. Salome, is now a well proportioned woman, beckoning Herod’s attention, as she dances. She makes eyes at Herod, who, despite the attractive bare-breasted woman sitting next to him (is this Herodius?) is clearly appreciative of Salome’s advances. No wonder, when only a see-through scarf covers over her scantily clad body.

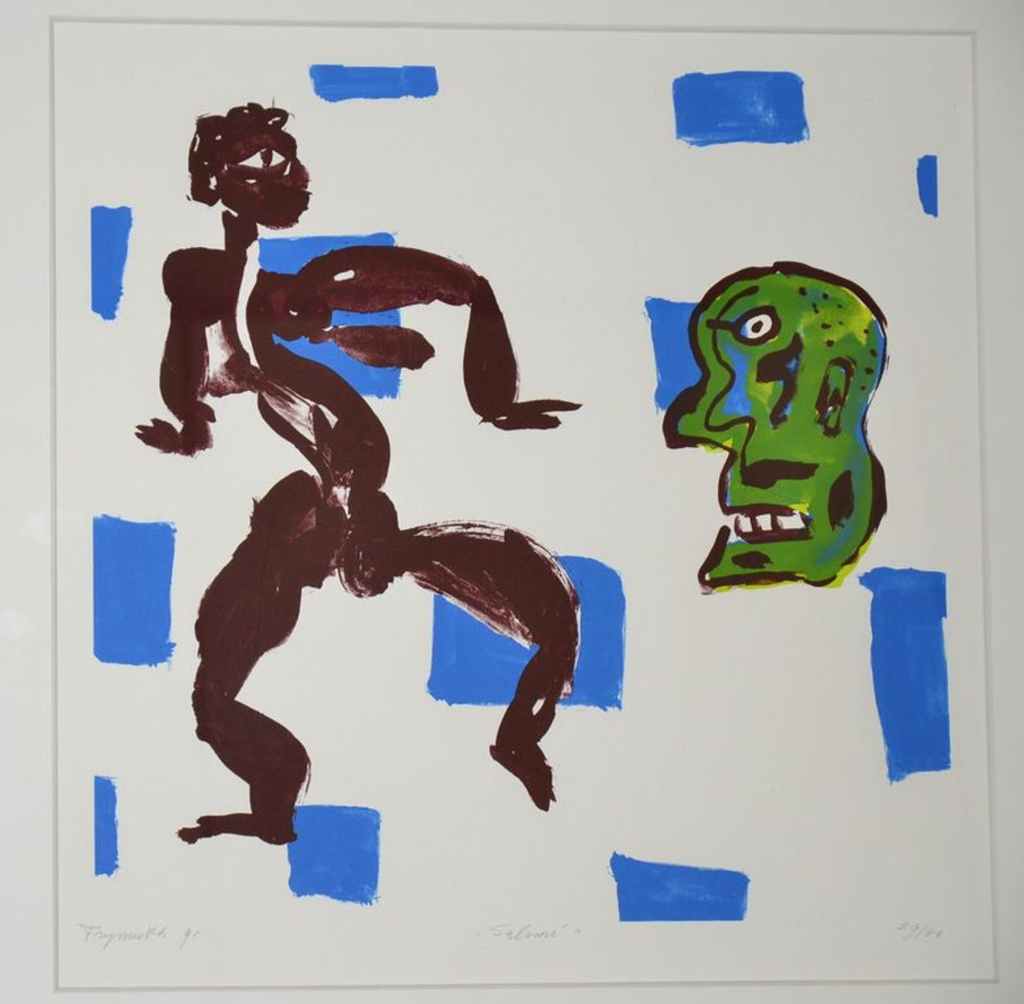

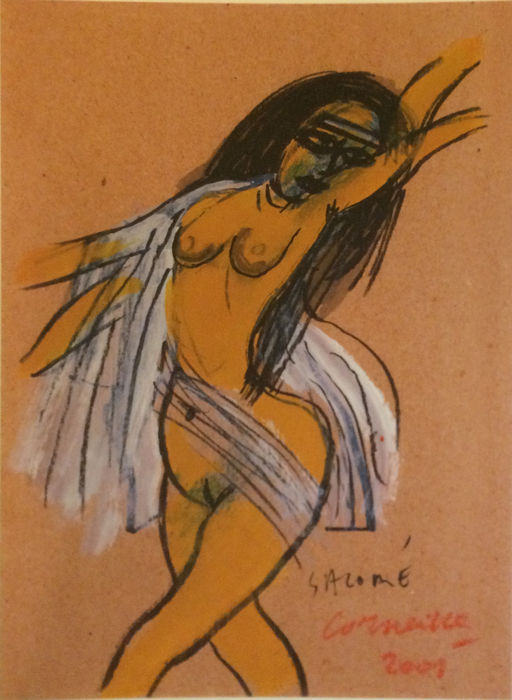

More than a century after Oscar Wilde bombarded Paris with his version of Salomé, this femme-fatale, has not lost her magnetism. Alphons Freymuth’s Salome may not be dancing in the traditional sense of the word, but this androgynous figure is definitely moving. And in these contemporary times, what, you may argue, is the difference between movement and dance? Whatever the answer may be this figure, frightened, sprints as fast as possible away from the apparition of the decapitated head of John the Baptist. Corneille, one of the founders of the Cobra Movement, created an entire Salomé series in 2001. His dancing Salomé is blatantly naked, leaving nothing to the imagination. The veils, often used to give some semblance of modesty, hover haphazardly over her shameless body.

What do we actually know about Salome? * Her name is not even mentioned in the gospels of Mark and Matthew. How old was she? Was she a young girl, an adolescent of a blossoming young woman? And how did she dance? All we are told is that her dancing greatly pleased Herod. Salome, to this very day, is an enigma. Knowing so little about her makes her free-game for any and all artistic interpretations. The enigmatic Salome never fails to inspire.

* See my previous two posts for more background information on Salome.