Salome, the name alone, conjures up images of an alluring young woman whose beguiling dance incited the beheading of John the Baptist. The narrative of Herod’s banquet appears in the New Testament, in the books of Mark and Matthew. Salome is not named in either book; the dancing girl is identified as ‘the daughter of Herodius’. The name Salome was first to be read in the writings of Jewish historian Flavius Josephus (377 – c. 100 CE), who, incidentally, made no mention of her dancing. Neither Mark nor Matthew describes how the young girl danced; Mark simply writes that Herodius’s daughter ‘came in, and danced, and pleased Herod and his guests’. Matthew’s narrative contains no more information and yet this dancing girl, about whom we know so little, has inspired artists for over a millennium. The young girl, whom from here on I shall call Salome, has been a topic of constant study and speculation, making her a prominent motif in art. Artists have portrayed her dancing, presenting the head of John the Baptist to Herod, and though not mentioned in the biblical text, dancing with the decapitated head. In this post, I will limit myself to Salome the dancer, looking, for the most part, at the artists of The Low Countries though allowing myself leeway to occasionally take a glimpse elsewhere.

The first known image of Salome actually dancing can be found in the Evangéliaire de Chartres, an illuminated manuscript from the second half of the 9th century. Then, as time passed, images of Salome became more acrobatic. She is pictured, standing on her hands, performing back bends and accomplishing other gymnastic feats, on church doors, tympanums, column capitals, on stained glass windows and in illuminated manuscripts. The medieval church perceived jugglers and tumblers as a hazard and condemned their contorted, distorted movements. The acrobatic Salome was not considered an innocuous dancer. Rather, the fourth century Church Father, St. Chrysostom sums Salome’s amoral dance up, when he writes: For where there is dance, there also is the Devil. For God has not given us feet to use in a shameful way but in order that we may walk in decency, not that we should dance like camels…’. It goes without saying that both church and society, considered the twisted, distorted Salome as wicked, malicious and the personification of depravity.

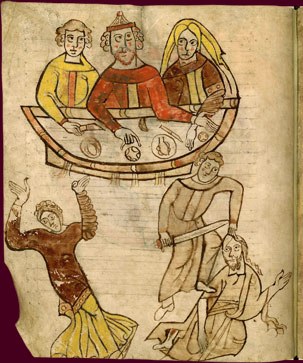

The acrobatic Salome, though widespread throughout Europe, is rarely seen in the art of The Low Countries. Possibly the closest example is a manuscript made in the Amiens area in 1323, purchased for the collection of King William I in 1819, and now housed at the Royal Library in The Hague. The right column of this bas-de-page illumination shows Salome in an extraordinary acrobatic feat. The opposite image shows Herod, Heriodius and a guest, visibly thrilled with Salome, who presents the head of John the Baptist on a platter.

Renaissance Italy revealed a different Salome; always beautiful, sometimes unworldly and at other times provocative, bewitching or downright dangerous. This is the Salome that the artists of The Low Countries, from the 16th century onward, depicted. According to Karel van Mander (1548-1606), artist and writer of Schilder-boeck, the Flemish artist Pieter Coecke van Aelst (1502-1550) travelled to Rome. Although there is no written evidence of this journey, his drawing, a design for the right panel of a triptych, Scenes from the Life of John the Baptist, is definitely influenced by Italian art and architecture. His Salome is a beautiful young woman, as graceful and determined as her Italian counterpart. Van Aelst presents a pagan court. There, the infamous Salome dances irresistibly as she plays her castanets. The audaciously sprawled musician is undoubtedly delighted.

The Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, houses a series of fascinating glass roundels describing the life of John the Baptist. Even though no original drawings have survived, it is believed that these roundels were designed after Pieter Coecke van Aelst. One of the roundels,The Dance of Salome, illustrates the seductive Salome, dancing for Herod and Herodius. Her dancing is so overwhelming that Herod averts his head, but, even then, he cannot resist this enticing creature. Where the Salome in van Aelst’s drawing could perhaps still be seen as a titillating dancing girl, this Salome is the embodiment of sensuality; her twisted torso, her determined focus, her inviting arms and her protruding hips leave no doubt as to her intentions.

In the 16th and early 17th centuries, most artists in The Low Countries chose, or were commissioned, to paint Salome complacently presenting the head of John the Baptist to Herod. Therefore, images of Salome the dancer are only found as part of a series of prints or engravings celebrating the Life of John the Baptist. In one of these series, designed by Maarten van Heemskerck (1498-1574), Salome is shown as a striking, self-assured woman. Her entrance is stunning. This is not a young, manipulated girl. This woman demands attention. She looks self-assured in the direction of Herod, who, together with some of the other men, reciprocates her overpowering gaze. Van Heemskerck’s Salome is compelling, is dramatic, her fashionable dress prominently accentuating her breasts and highlighting her blatant sexuality. Contrary to most images, Herodius is not seated at Herod’s table; she and her daughter can be seen whispering behind-the-scenes.

Most images of Herod’s banquet show a handful of guests sitting upright at a table. Occasionally, especially in Renaissance Italian images, the feast could be presented as a grand celebration with a large number of men and women. The above image ‘after Jan van der Straet’, showing numerous guests, is a unique example. I know of no other image, by an artist born in The Low Countries, where Herod’s banquet takes place along an extended table with men, lounging on oriental rugs in cinematic Roman style, ogling the enticing Salome as she makes her entrance. It is not clear how this Salome dances, but she has lifted her skirt, much to the pleasure of the reclining men and the enthralled dwarf. The reposing Herod, reminiscent of a well-dressed Bacchus, is speaking with Salome. This conversation is depicted as a type of flashback, having taken place before Salome’s dance. A familiar practice, often used in prints, was to show different moments of the narrative simultaneously; at the right, Herodius is speaking to her daughter on the back balcony, and to the left, John the Baptist is beheaded under the vault. Simultaneously, the main scene depicts Herod’s banquet. This engraving by Cornelis Galle after the Flemish artist Jan van der Straet (1523-1605) is, as so often seen in The Low Countries, part of a series about the life of John the Baptist. Jan van der Straet, also known by his Italian name Joannes Stradanus, was a prolific and versatile artist who worked at the Medici court in Florence.

Prints, like this one, were produced in large quantities. They were lightweight, relatively cheap and easily transported. And travel they did, even as far as Peru. It is interesting to compare Jan van der Straet’s engraving with The Dance of Salome by Quechua painter Diego Quispe Tito (1611-1681), who worked in Peru his entire life. Inspired by Flemish models, he created a series of paintings depicting The Life of John the Baptist for the San Sebastian Church in Cusco in Peru. The similarities between van der Straet’s engraving and Quispe Tito’s painting are unmistakable; the long table, the reclining Herod, the dwarf, the musicians and, of course, Salome, who looks shamelessly at her audience as she suggestively lifts her elaborately decorated skirt.

The Flemish painter, draftsman and etcher Pieter van der Borcht (1530-1608), produced a series of etchings for the biblical album, Emblemata Sacra, including, The Death of John the Baptist, shown above. As in van der Straet’s engraving, this etching shows scenes before, during and after the death of John the Baptist. Herod’s banquet, though not the main subject of the etching, shows the guests dining and enjoying the sound of the trumpeters, who are playing at the foot of the stairs. This youthful Salome is probably skipping or hopping; her skirt flutters freely around her legs. Effortlessly, Salome swings her arms and torso in a joyful, spirited dance. She is charming, a carefree dancer, perhaps even an innocent maiden who, unconsciously relinquished to the contemptible manipulation of her mother.

In Gouda, an historical city, famed for its cheese and candles, stands the Church of Saint John with seventy-two stained-glass windows. Many of the windows hail from the 16th century. The top tier of window 19, shows Salome, a fashionably dressed young woman, accompanied by a lyrist, dancing before Herod and his guests. She is a tall young woman, confidently placing her hands firmly behind her hips. She is obviously quite beautiful, turning not only the head of the musician, but commanding Herod’s attention as he opens his arms widely to acknowledge her. This scene, part of a seven-meter-high window, telling the story of John the Baptist, is the work of the Haarlem-born glazier, Willem Thybaut. Although stained-glass windows showing Salome dancing are not uncommon in Europe, this window is unique in The Netherlands.

After the Renaissance, artists from all countries were inclined to paint Salome as a beautiful young woman presenting the severed head of John the Baptist to Herod. The artists of The Low Countries followed suit, but also continued to paint Salome as a dancer. From the 16th century onward, a few artists from Flanders and the Northern Netherlands placed the young voluptuous dancer in the spotlight; the following post will look at images of the dancing Salome from the late Renaissance to the 18th century.