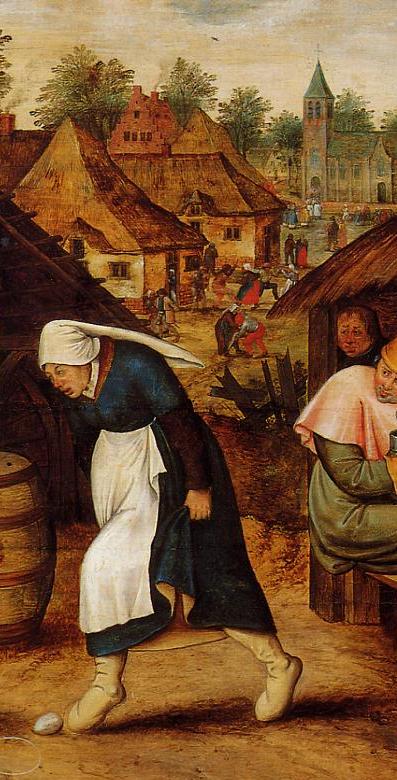

A kissing couple, a monk fondling a tankard, a musician playing a vedel, a woman with a pot on her head, a kermesse and church procession all form the decor for Pieter Brueghel the Younger’s portrayal of an egg dancer. The Egg Dancer, from around 1620, shows, contrary to many other images of an egg dance, an old, stooped peasant woman, attempting to nudge an egg into the bowl. Where all the previous egg dancers were young, swift, athletic or energetic men jumping or hopping around on one leg, their hands placed firmly on the waist, this old woman in flabby footwear, hitches up her long cumbersome skirt and looks thoroughly exhausted as she earnestly continues her dance. Hopping and jumping are out of the question, but, just how is she to get the egg into the bowl? Since both feet are on the ground I can only imagine a type of shuffling step where she moves the front foot forward, displacing the egg, followed by the back foot quickly trailing in. A difficult feat; all the more since the plodding peasant is not even looking at the egg, but at a spot just past the bowl.

Half a century earlier, 1558, the Flemish engraver Frans Huys, published an engraving of an egg dancer. This work, in the Rijksmuseum, called Peasant woman dancing the Egg Dance, was designed by the Flemish artist Cornelis Massijs and is remarkably similar to the 1620 painting; it is safe to assume that Pieter Brueghel II was familiar with Massijs’s composition. As in Brueghel’s work our attention is drawn to a somewhat older dancing peasant woman positioned firmly in the centre of the image. This peasant has removed her clogs, dances in stockings, looking, even though she leans forward, determined to get the egg into the bowl. Compared to the Brueghel dancer, she is less earthbound, more active and, perhaps, prepared to attempt a few hopping steps.

The original engraving may not have a kissing couple, but has a dog dressed in a fool’s cap sitting on a barrel, a woman, with a pitcher in hand, looking tenderly at the man sitting next to her, and a long rod, with hanging loop, extending from the roof of the tavern. And why has the woman next to the open a pot on her head? Is she about to perform a balancing act? This is a tavern of folly, a place of ill-repute. The main difference, between the two egg dances, however, lies not in the foreground. Both artists, by way of the narrow opening between the tavern and shaded picnic table, draw the viewer into an intriguing vista. Cornelis Massijs confronts the viewer with a harsh message. Massijs construes the feast loving peasant, much in the manner of Hieronymus Bosch, as the symbol of frivolity, foolishness and impiety. The barren tree and the burning houses offer a glimpse of the suffering the peasant’s levity will provoke.

The Egg Dance by Pieter Brueghel II is far less harrowing. Looking past the dancing woman, a village scene appears where some villagers are walking in a procession, some are praying, and others are enjoying themselves in a variety of earthly ways. Besides the intoxicated man being led home by his wife and a man unashamedly groping under a woman’s skirts, various couples are dancing. The dancers, though very small in this painting, are typical of the dancers seen in many of Pieter Breughel’s II paintings. They are accompanied by a musician playing the bagpipes; an instrument known for its lustful implications. This painting, though not without symbolism, depicts the religious and the worldly existence of peasant life on a sunny festive day.

The traditional egg dance remained a popular pastime in the Low Countries during the 16th and 17th centuries. In 17th century art, the egg dance is regularly to be found in a tavern setting. Scenes from everyday life, genre art, were endearingly painted by both Dutch and Flanders artists. Haarlem, at the time a major art centre, was home to various genre painters. The prolific Haarlem born painter, Jan Miense Molenaer (c. 1610-1668), who incidentally painted numerous dance scenes, was famous for his genre art. He painted various paintings of egg dances; all situated in dark, run-down taverns where card players sit around wooden tables, couples caress and habitués drink and make merry.

(click on each image to expand)

In the above paintings, the traditional egg dance, where one dancer displayed his dexterity, changed, to become a couple dance. Revellers of all ages hazard a go at carefully placing the fragile egg back into the bowl. They hop, skip or caper in unison; the fiddle and the bagpipe, both instruments associated with the peasant folk, being the favourite musical accompaniment. The dance is all part of the evening’s fun; more often than not, one of the dancers clings onto a flask of ale or a glass of wine. Looking at the demeanour of the other rollicking guests, just barely, to be seen in the background, we can assume that the dancers, too, are more than a little tipsy. The old couple (centre image) have managed to place the egg into the bowl, but, the other couples, appear a little unsteady; I doubt if they will be so successful.

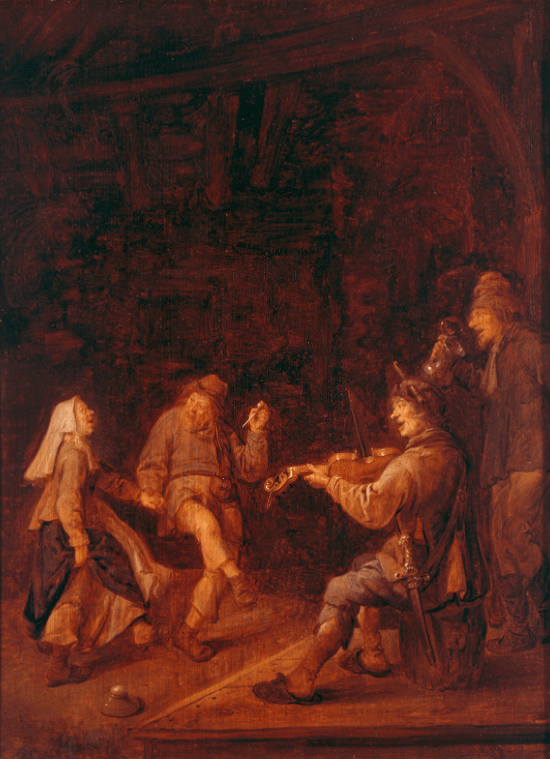

Another artist with the surname Molenaer, Jan Jacobsz. Molenaer, whose relation to Jan Miense Molenaer is not known, also worked in Haarlem. His version of the Egg Dance takes place in a crowded tavern, full of playing, drinking, smoking and cuddling merrymakers. Even though the dim light makes it impossible to distinguish the characters individually, you can still see that these guests are a rowdy bunch of folksy peasants. At the back of the tavern, sitting on a platform, a fiddler entertains the rustic crowd. As if standing in the spotlight, an unusual, even out of place, the couple has taken to the dance-floor. This couple, the egg dancers, wears finely designed clothing. The man’s vest is decorated with tiny pearl-like buttons. His partner, besides her splendid dress, wears delicate earrings and a hat that any peasant woman could only dream about. We can only guess as to the identity of this novel couple. They may be the land owners, town folk or just travellers staying a night at the tavern. But they are not the type of egg dancers, we have come to expect.

Where the peasant egg dancer danced intuitively, improvising steps and movements as he navigated around the egg, the above couple are elegant, carry themselves stylishly and even though they too may improvise on this specific occasion, their dance is totally different to the fellow revellers. The artist has captured the man, who is wearing fashionable black shoes laced with fine ribbons, in an intricate foot position, revealing his dance training. These egg dancers, befitting their social status, retain their grace and decorum, despite the coarse surroundings. Jan Jacobsz. Molenaer juxtaposes the rough world of the peasant with the polite world of the upper class; something rarely seen in egg dance images.

Jan Steen, does nothing of the sort. His version of the egg dance takes place in a tavern where everyone, all the village folk, is having a great time. The tavern is crowded, amorous pairs are walking up the stairs, a well-dressed lady is being lured into the tavern by a shady man, children are playing and dogs are joining in. The bagpiper and the maid, holding an open vessel, blatantly invite the viewer to join in with this boisterous bedlam.

At the foot of the stairs peasants revel in a spontaneous, improvised dance. Previous egg dances have all been executed by one or two dancers. To my knowledge, Jan Steen’s version with four dancers is unique. The egg lies in the centre of the dancer’s circle. Scrutiny reveals a chalk circle drawn around the egg. Jan Steen’s dancers, here and in his other paintings, are exuberant. They toss their bodies cheerfully to and fro, giving the impression that they are really moving. The back women’s face catches the light, and our attention. She is vibrant, fun-loving, dancing without a care in the world. The front woman looks down, perhaps suddenly realizing that her foot terribly close to the egg. But no one seems concerned; the dancers continue merrily on their way. Jan Steen was a brilliant storyteller, a master of characterization and had an extraordinary ability to suggest movement on canvas. His dancers were movers, energetic, spirited and full of fun, but more about this in a future blog.

The egg dance rarely appears in artworks from the Low Countries after the 17th century. It, however, remains a popular folk dance in various countries, especially in Great Britain. Another tradition, during Easter, is to arrange twelve eggs in the form of a Latin cross where a dancer moves between them as though they were posts. Dancers are known to perform this trick blindfolded. A blindfolded version of the egg dance features in Goethe’s novel Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship (1795). And recently, Saatchi Art presented a new interpretation of the Massijs/Brueghel Egg Dance by British artist Corinne Hamer. Traditions may change over time, but in one form or another, the egg dance is here to stay.