In my previous post, I looked at images of the basse-danse in medieval manuscripts created during the Burgundian era. This post looks at some of the many images of circle dances illustrating secular manuscripts of the Low Countries during the same period. Circle dances have existed since the dawn of civilization; men and women, boys and girls join in a communal dance, be it a religious dance, a ritual, a folk dance or a social dance. The circle dance belongs to all nations and all ages. In Burgundian times, illuminations of people dancing in a circular formation illustrated chronicles, histories, romances, travel and moralistic literature.

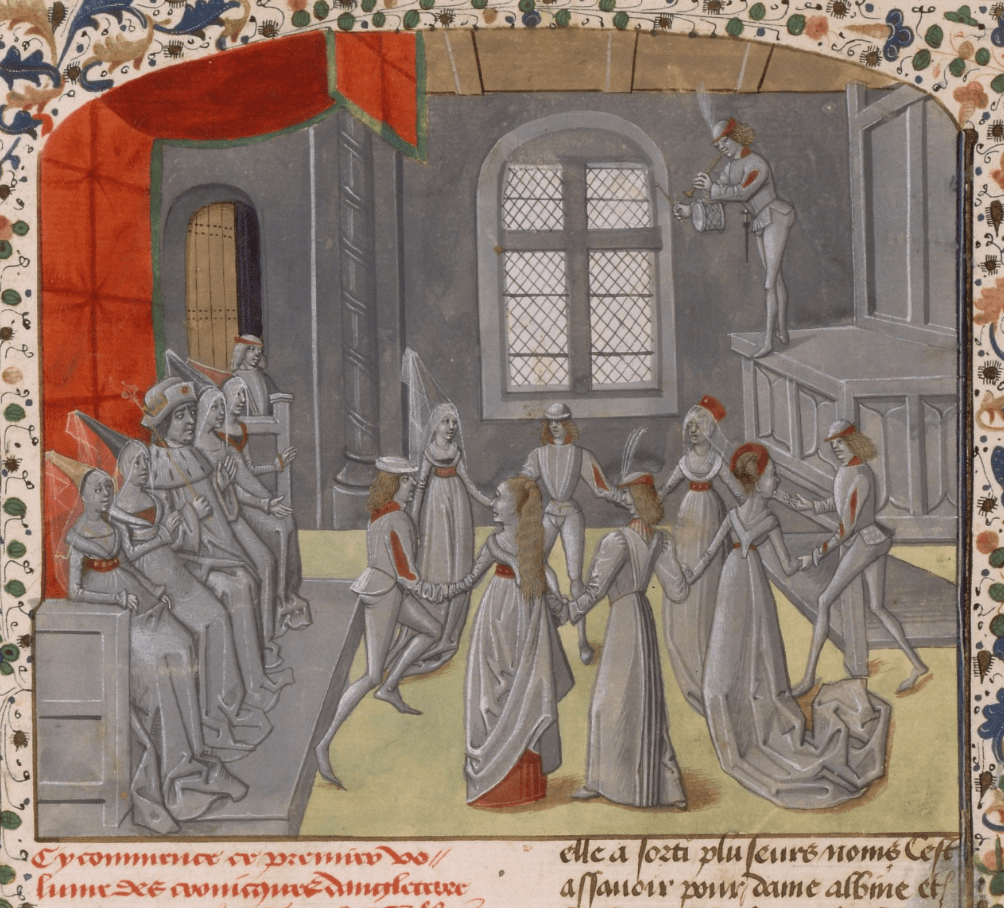

Let us start by revisiting the Chronicles compiled by the French chronicler, Jean de Wavrin. In Chronique d’Angleterre, de Wavrin recounts the legendary tale of King Diodicias and his thirty-three daughters. This vast manuscript, made in Bruges, contains only one illustration and that sole illumination is a remarkable grisaille of a circle dance at the court of King Diodicias. The artist of this exclusive illumination remains anonymous, but the style is reminiscent to that of the famous Flemish illuminator, Loyset Liédet.

In a simple court setting, the daughters of Diodicias and their suitors, dance in a circular formation. Diodicias, himself, flanked by more of his daughters is seated on a long wooden bench. Playing a tabor and flute, the musician stands alarmingly close to the end of the ridge, but despite his perilous position he has a jolly expression, keenly observing his dancers. The dancers, dancing hand in hand, wear stylish aristocratic attire. Taking my clue from the gentleman capering just in front of Diodicias, I would say that the circle is moving to the left. This same sprightly gentleman is vigorously hopping, perhaps galloping to the side. All very puzzling, considering that the remainder of the group is quite composed, except, of course, for the gentleman on the right who is possibly being reprimanded for arriving late. And, I wonder if those three ladies, handling a long and presumably heavy train, could even manage to move quickly; their movement range is surely limited to elegant striding and subtle shifts of weight. To my mind, the artist has chosen to include this vibrant fellow to enliven the scene of an otherwise easygoing dance. Regardless, Diodicias and his seated daughters are amusing themselves.

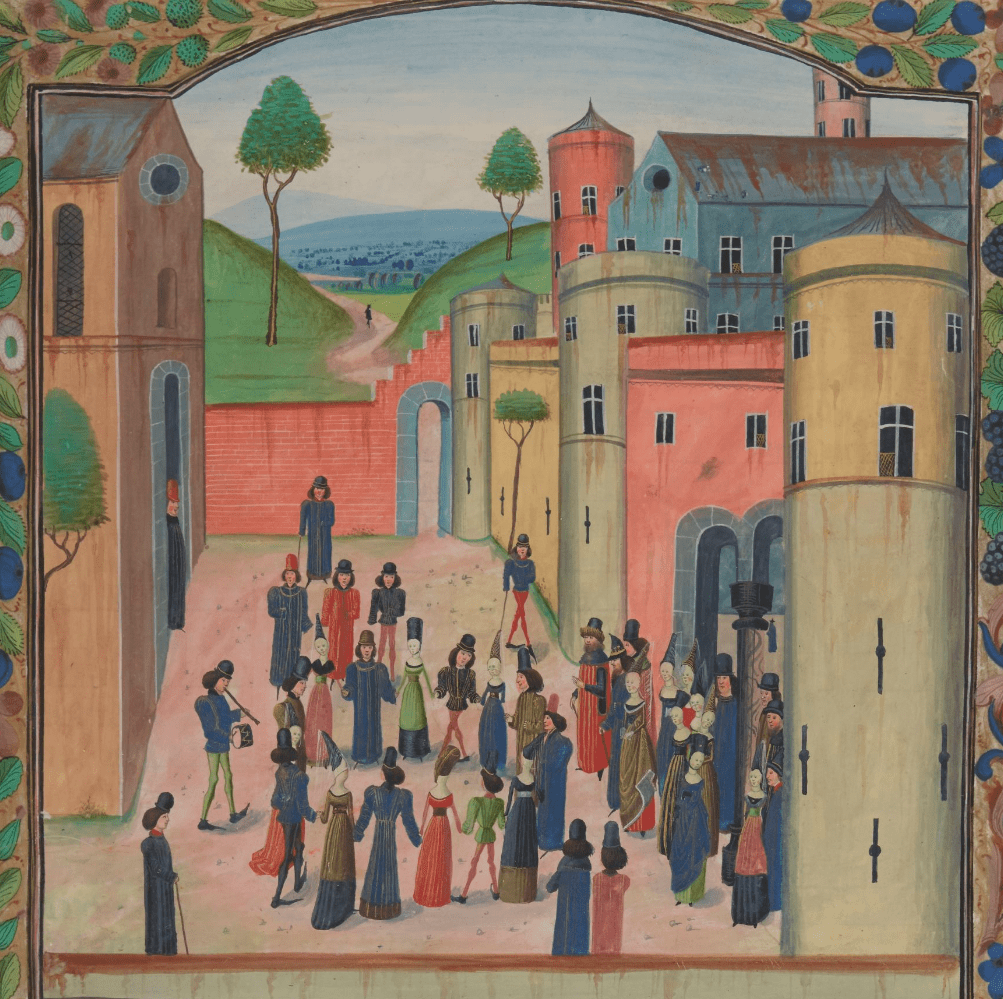

This multi-coloured illumination of a round dance decorates yet another version of Wavrin’s Chronicles (BnF français 76). The scene takes place outdoors, at Windsor Castle, then domicile of King Edward III (1312-1377). In a fairy-tale like setting of the castle and the surrounding grounds, the anonymous Flemish artist, arranges a large group, of mostly young men and women, in a circular formation. This chain, however, is not entirely closed; on the right, the man in brown extends both hands forward as if addressing the group. The dancers and all the observers are long, skinny match-like figures and occupy approximately the lower third of the drawing; the remainder of the space being claimed by the architecture and a far vista of the countryside. Their dance, presumably a branle, is accompanied by a single musician playing, as in the top illustration, a tabor and flute. All, including the observers, are fashionably dressed. The women are elegant in their long gowns, complemented by various forms of high headdresses and some of the men, as was fashionable at the time, also wear long robes. Others wear simple tunics and hose and all wear the long pointed poulaines as footwear. The dance is restricted to stepping movements in different directions, a low kick of the leg and possibly a gentle hop, though, taking the ladies’ trains into consideration, turning would be improbable. A branle, the name derives from the French ‘branler’ meaning ‘to sway’, travels from side to side either by means a simple stepping step or as the gentleman donning a bowler hat demonstrates, via a crossover step.

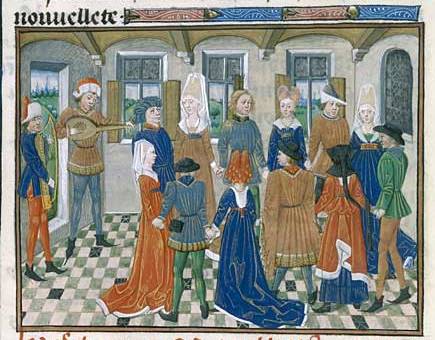

Facta et dicta memorabilia, is the abbreviated title of a set of nine books written by the Roman author Valerius Maximus during the reign of the emperor Tiberius, discussing vice, virtue, vanity, merit, superstition and a variety other subjects. This moralistic manuscript, translated from the Latin by Simon de Hesdin, was immensely popular during the late Middle-Ages, even serving as a guide book for the elite and a textbook for scholastic studies. The illustration on the right features in a manuscript that once belonged to Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy. Maximus scrutinizes life in Rome, using legends and anecdotes as analogy. He does not mention dancing as such, but does refer to theatre, banquets, bath houses, and other forms of luxury; various Burgundian illuminators chose dance and dancers to illustrate that luxurious way of life. All the figures in the above illustrations belong to the upper classes; both the men and women are impeccably dressed, dancing in a stately setting. And yet, there is more than meets the eye. These chain dances, of noble men and women, are not merely an illustration of the elite enjoying themselves; the illumination has a didactic purpose. You may recall that the emperor Tiberius not only banished dancers from his court, but, also banished them out of Rome and that statesman, philosopher Cicero, orated ‘if a Man be a Dancer, he is doubtless either a Drunkard or a madman’. No virtuous woman would consider dancing and those who dared to dance were associated with harlotry. Basically, in Tiberian Rome, it was considered disgraceful for a free citizen to dance, except in connection with religion. The circular dances shown above, are not merely decorative, but, underline the moral lessons promoted by the highly valued writings of Valerius Maximus.

Images of nobles dancing at court, dancing in enchanted gardens, dancing within enclosed walls illustrate some of the finest medieval literature. Almost every edition of Le Roman de la Rose, the celebrated secular manuscript of the late Middle-Ages, contains an image of dancers dancing a carole. There is much uncertainty as to how a carole was actually danced; a line dance, a circular dance or even a combination of both. What we do know is that there was no single way of dancing a carole and usually the dancers accompanied themselves with their singing. Needless to say, the choreographic possibilities of any medieval dance are determined by a number of elements, but most importantly dress and space. The voluminous, cumbersome robes, as worn by the ladies in the above two miniatures, indicate that the movements of these dances are neither complex nor hurried. Both take place within a restricted space, making the circle formation the most obvious choice. A musician is nowhere to be seen, suggesting, that even though the dancer’s mouths are closed, they may be humming or murmuring, or that the artist has simply taken for granted that there is a musician standing somewhere in the neighbourhood.

The 15th century tale, about the valiant knight Gérard de Nevers, (above right), who encounters dragons and giants in between performing his knightly duties, attending banquets and observing the etiquette of courtly love was a celebrated manuscript, making fun of the traditional knight literature. Loyset Liédet, the prominent Flemish artist, illuminated a profusely decorated manuscript originally made for Philip the Good and finished under the rule of his son Charles the Bold. Liédet known for long and slender figures shows a fairly formal circle giving absolutely no clues as to how the group dances. The men’s feet are all facing different directions; forwards, sideways or in a position not dissimilar to the balletic second position. The women are no help; they look so disinterested.

Le Champions des Dames, dedicated to Philip the Good, is a long allegorical poem defending the honour and reputation of women, written by Martin le Franc between 1440 and 1442. A number of manuscripts exist, including the Grenoble 1465-75 copy, illuminated by an artist from Lille, known only by his notname, Master of the Champion des Dames, which contains 179 extraordinary miniatures. The Master’s style is unique; his figures are long and slender, painted in watercolours, tinted gently in hues of mauve and blue. Equally striking is the total disregard for realistic proportions and that, at a time, when Flemish realism was prominent. The dancers in the enclosed garden are disproportionately tall in comparison to the surrounding dwellings and structures, not to forget the imposing musician whose hat towers high above the houses. Naturally, dancing in a relatively confined space, as these dancers do, imposes limitations on spatial design and the scope of movement variations. Yet these dancers are not at all static; they step sideways, forwards and backwards. This circle is constantly changing in shape and in direction, making simple patterns that suggest a branle or round dance. And this all happens under the watchful eye nude lady, whose only covering is a diaphanous veil.

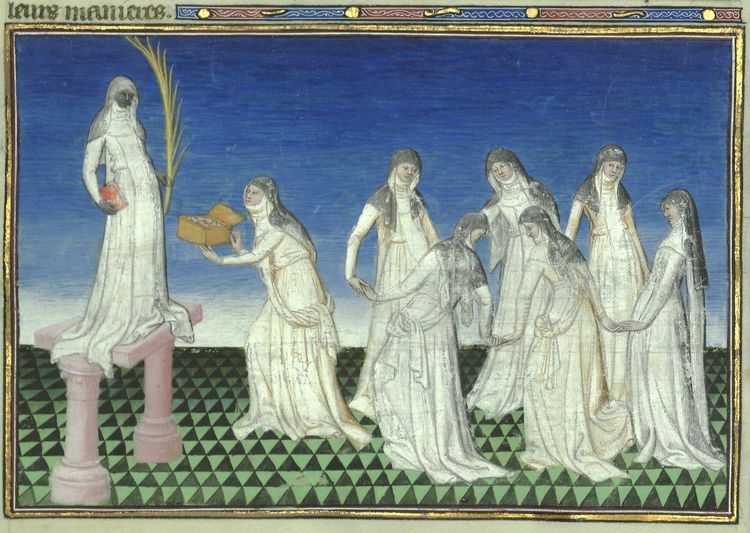

Travel, adventure, mystery and exoticism all merged together in Livre des merveilles du monde, an extraordinary manuscript, recounting the explorations of Marco Polo and other adventurers written, between 1410-12, under the patronage of John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy. Colourful illuminations, produced in the workshops of the Bedford Master and the Flemish illuminator Bouricaut Master, follow each other, page after page. Nearly all the illuminations are bathed in sunlight, displaying dazzling bright blue skies and luscious green vegetation. The left illustration, from the Adventures of Marco Polo, is an exception; this tempered scene displays a group of women performing a serene dance of worship. The illumination, attributed to the Bouricaut Master himself, is remarkably expressive revealing delicate rotations, soft waves and torso movements not seen in any other illumination in this blog. On the right, amid an abundance of colour, a circular dance takes place on a platform surrounded by mythical and mysterious creatures. The colours are enticing, the movements, especially the man in the black hat, are lively and the facial expressions are compelling, so much so, that one becomes curious to hear what the king is saying.

Artists of the Middle-Ages, just as artists in the following centuries, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Hans Bol, Martin van Cleve to name but a few, found inspiration in the ritual, social, and communal characteristics of this everlasting dance form. The circle dance is universal.