The court of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy is legendary. Not only were the palatial banquets, the stunning tournaments and the great pageants magnificent, but Philip the Good (1396-1467) was also a great patron of art and culture. Under his patronage the arts, including the art of the illuminated manuscript, thrived. The Duke was a bibliophile; his library housed more than seven hundred volumes. Many of these manuscripts are luxuriously decorated with miniatures and with countless marginalia. Manuscripts were treasured; they were status symbols. Philip the Good commissioned more than sixty books, including historical chronicles, romances, devotional books and other religious writings. Flanders became an important manuscript production centre and Flemish artists flourished.

At the Burgundian Court the fashionable basse danse was enjoyed by the aristocracy and the well-to-do. A unique, late 15th century manuscript, Les Basses Danses de Marguerite d’Autriche, once belonging to Marguerite d’Autriche, daughter of Marie of Burgundy, notates fifty-eight different variations of the basse-danse together with their accompanying musical score. This exceptional manuscript, one of the earliest known dance manuals, indicates the significant status dance held at the Burgundian Court. In this post, I will discuss images of the basse-danse that appeared in diverse manuscripts created in this illustrious environment.

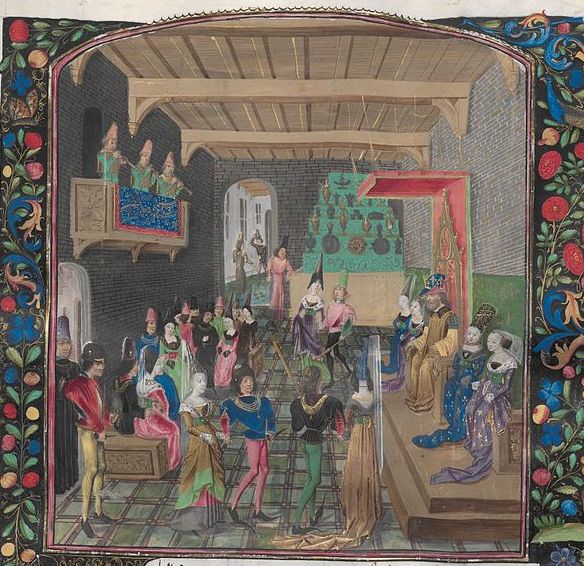

Jean de Wavrin (c.1400-c.1474), a French chronicler compiled a set of chronicles, Recueil des croniques et anchiennes istories de la Grant Bretaigne, encompassing the entire history of England, starting from legendary foundations and working through to his own time. The two illustrations shown above, miniatures from his extensive chronicles, present a legendary event prior to the dawn of Great Britain. The scene represents a feast celebrating the betrothal of the thirty-three daughters of the fabled Syrian king Diodicias. Notable, is that the two independent artists have located this ancient story in a typical Burgundian court setting. Every detail, the architecture, the dress, the musical instruments and the dancing has been placed within a 15th century context. The enthroned King Diodicias, is flanked by some of his devoted daughters, watching even more of his dutiful daughters and their intended, as they promenade gracefully to the melodious strains of the musicians playing on the upper balcony. Apparently these ancient ladies and gentlemen were fully conversant with the medieval basse-danse. This elegant, stately dance, as the name implies, is a low dance. No surprises there; just imagine trying to jump in poulaines, those long extended shoes, that the men are wearing. And it goes without saying that the ladies high headdress (conical hennin), heavy dresses and long trains would make fast and lively movements nigh impossible. The late-medieval basse-danse had a processional form where couples progressed gracious and unhurried around the dance-floor. This court dance, apart from the révérence, was composed of four steps, namely, pas simple, pas double, the reprise and the branle. These steps, according to the particular variant performed, differed in quantity and order.

(Loyset Liédet, was a prominent Flemish illuminator, who worked exclusively for Philip the Good and after his death for his son, Charles the Bold.)

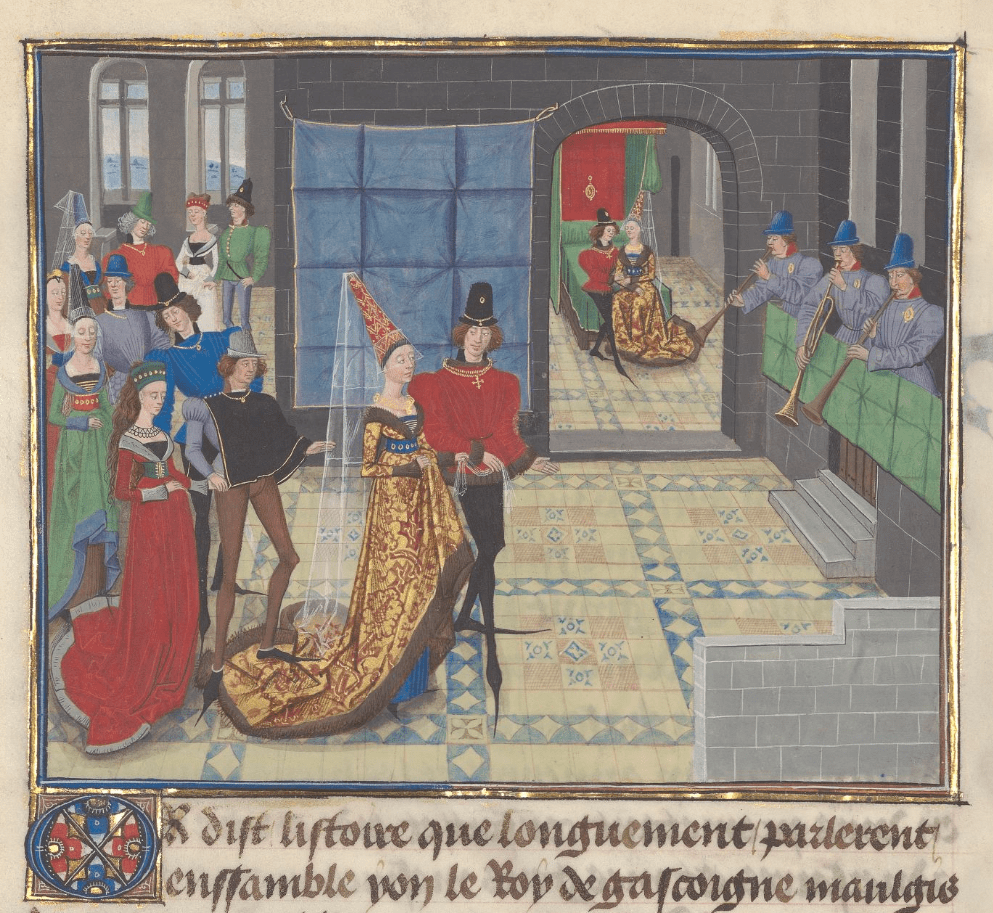

Images of the basse-danse occasionally appear in chronicles, in romances and in other popular literature. In the manuscript Roman de Renaud Montauban, a tale about a fictional 12th century knight, there is an interesting miniature by Loyset Liédet, which depicts the marriage of the hero, Renaud, and his bride, Clarisse. The bride and groom together with their guests perform a serene processional dance. The dancers glide or walk in close formation, making it necessary to take small controlled steps. Their bodies are poised, and, except for an occasional hand gesture or slight tilt, their torsos are calm and carried with regal elegance. The man behind Renaud, however, is not very observant; this clumsy fellow is standing on the bride’s train. Liédet is known for his characteristic style; all of his figures are long and slender, rather formal and mannered. Liédet is also known for the continuing narrative within his illuminations; in this case Liédet draws us through the archway into the newlyweds’ bedroom.

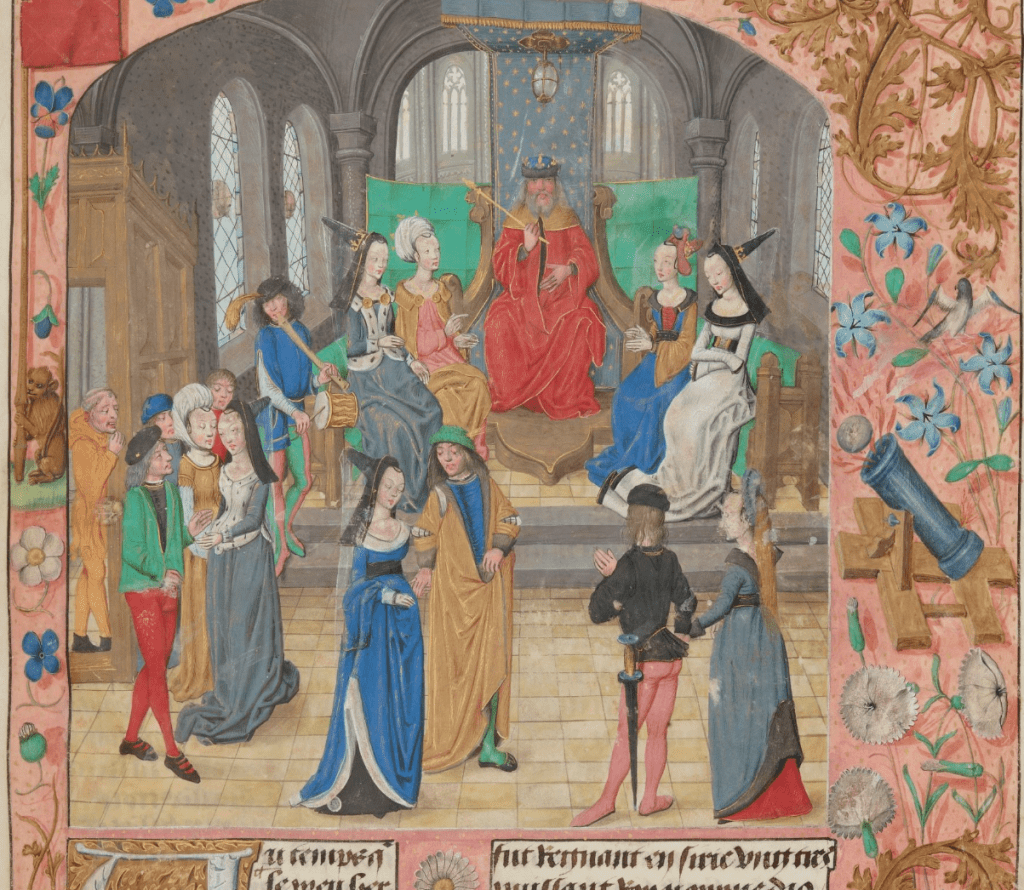

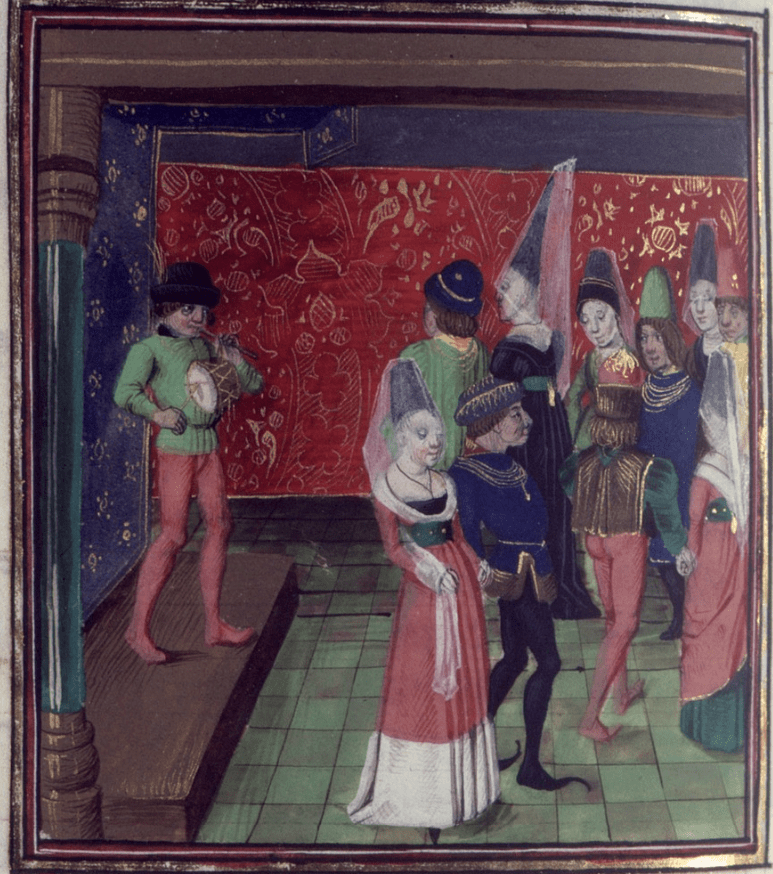

In comparison, the above illumination, of the betrothal celebrations of the daughters of King Diodicias, on the opening page of the romance Guiron le Courtois, is not at all stilted. Each couple is unique and the figures are positioned casually around the dance floor. These couples walk leisurely side by side, turn freely towards each other, have a greater movement possibility yet retain their regal composure. The men, without the unpractical poulaines, are no longer limited in their movement and the ladies, though still wearing heavy gowns, are less inhibited by their headdress than their counterparts in the previous images. The artist, the Master of Edward IV (active 1470-1499) is known to dress his figures in different costumes, to use a variety of headdresses and to accent a lady’s cheek with a touch of rouge. All these factors make the dance scene appear less ceremonious, so much so, that the processional characteristic of the basse-danse is no longer prominent. Identifying a specific dance form depicted in a miniature or painting can be challenging. But, in this example, it is feasible to assume that these elegantly poised couples are performing the basse-danse.

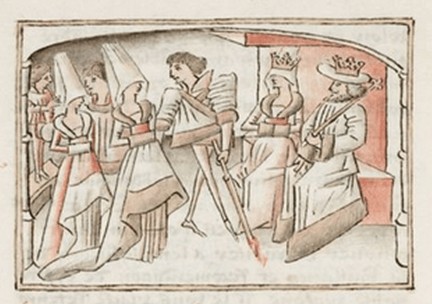

Chivalry romances, tales about knights, dragons, banquets, damsels in distress, courtly love are an ideal recipe for dance images. Cleriadus et Meliadice, a manuscript from the Southern Netherlands, that once belonged to King Edward IV of England (1442-1483) contains a one column miniature showing the principal characters seated, watching dancers perform in a great hall. This, to my mind a fairy-tale book image, shows court dancers dancing a processional dance to the sound of minstrels playing wind instruments. This is without doubt a miniature of a basse-danse; the original text discusses dance at court and specifically names the basse-danse (folio 171v). The romance, Gérard de Nevers, once in the collection of Philip the Good, contains around fifty illustrations created by the Master of Wavrin (not to be confused with Master of the London Wavrin). Working in Lille in the 15th century, the Master of Wavrin, was a most unconventional artist. The illustration of the dancing couples, shown above right, defines his style immediately. The figures are reduced to line drawings and the master pays no attention to detail and uses little to no colour. The dancers have an angular look, have disproportionately thin legs and arms and all the ladies wear a headdress that practically covers their eyes. Yet even though the master draws cartoon-like characters, his near sketches display movement as no other. Take a look at my post, Hieronymus Bosch – Moresca, to see the master’s dynamic depiction of a morris dance.

The left illumination, shown above, is a small column miniature taken from a medieval reproduction of the popular Latin manuscript Facta et dicta memorabilia, a series of books written by Valerius Maximus (Valère Maxime) during the reign of the Roman emperor Tiberius. Valerius Maximus discusses morals, vice, virtue, merit, superstition and various other subjects. The above miniature is the work of the Master of Margaret of York who was active in Bruges between 1470 and 1480. The illumination on the right is a small detail taken from the illustration placed at the top of this post; Jean Wavrin’s Chronique d’Angleterre is attributed to Master Anton of Burgundy.

I have chosen the above two miniatures to specifically look the deportment of the dancers. You may have noticed that the man in the blue doublet is standing in the rather awkward position; his torso is turned to the viewer while his feet moving forward, a position not unlike those seen on Greek vases. In fact, all the men in both illuminations have an uncommon posture. Their knees are slightly bent, their pelvis is tilted, they lean slightly backwards and their movement is mannered. The noble ladies, though less extreme, have a similar deportment. Just out of curiosity, I attempted to dance maintaining this contrived stance. I noticed that leaning backwards and moving forwards is possible, but feels unnatural. This is a cultivated posture and, if actually used in the basse-danse, would need sufficient practice to perfect. One observation is that each step takes the weight straight onto the heel, which, if the extensions of the poulines are indeed as long as the artist’s impression, then this specific posture makes it possible to dance without hindrance.

With only a few extant dance manuals, musical scores and a small collection of miniatures and prints to go by, our tangible knowledge of the Burgundian basse-danse is limited. It is tempting to consider the above illuminations as a primary source of information. Admittedly these illuminations give an appreciation of the basse-danse. We are given some insight as to the deportment, the musical accompaniment, the spatial formation, the placement of arms and hands, the dress, but the fact remains, that artists are, understandably, more interested in composing a favourable artwork than presenting a technically accurate dance representation.