28th of January 1393. Charles VI and five courtiers prepared themselves to perform a bizarre dance, at a feast held in honour of the wedding for one of the queen’s ladies-in-waiting. They appeared, in a then popular disguise, as wild men dressed from head to foot in garments, according to the chronicler Jean Froissart, ‘made of linen cloth covered with pitch, and thereon flax like hair’ (1). The costumes, that rendered them unrecognizable, were sewn fast to their bodies. The six men, Froissart informs us, looked like ‘wodehouses full of hair from the top of the head to the sole of the foot’(1). Five men were fastened together and the sixth, the king, unconstrained led the way.

These grotesque characters, according to the contemporary chroniclers, rushed into the hall performing queer gestures, displaying disgraceful positions, and making obscene gestures while howling like wolves. The spectators, Froissart tells us, enjoyed the masquerade marveling at the antics and capers of the men dressed like wodehouses. The dance ended tragically. The costumes, as you will remember from the previous post, were highly flammable. Someone, most often named, the Duke of Orléans, approached the dancers, igniting the costumes with a spark from his torch. Charles VI was rescued by the Duchess de Berry, the nobleman Nantouillet saved himself by jumping a tub of water and the four other dancers perished.

That ill-fated festivity was reported by three chroniclers, The Monk of St.-Denis (Michael Pintoin), the Valois Chronicler and Jean Froissart. There are seven known illuminations of Le Bal des Ardents, all, except one, illustrate the commotion and bewilderment of the spectators and dancers soon after the ‘wild man’ are set ablaze. This tragic event, about which Froissart wrote in Book IV of his famous Chronicles, made a great impact on both readers and artists. It is one of the few historical events that is illuminated in every illustrated Froissart Chronicles. All the illuminations discussed in this, and in my previous post stem from the Froissart Chronicles.

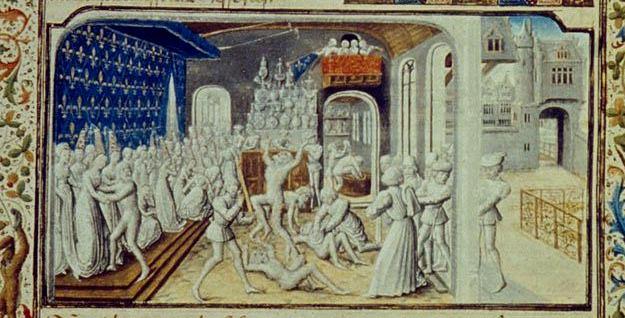

This lesser known illumination, from the Breslau Froissart, was created in the workshop of the famous Flemish illuminator, Loyset Liédet (1420 – after 1479). It may be the work of the Flemish illuminator Lieven van Lathem (1430 – 1493) or Philippe de Mazerolles, French by birth but active in Bruges.

The scene takes place immediately after the men are set ablaze. Looking straight at us, totally aghast, is the man possibly responsible for this horrific accident. It appears as if he is reaching out to the reader, stunned by the consequences of his reckless action. Behind him, a powerful scene showing four dancers in peril, is effectively exposed. One man, in desperation, stretches his arms and torso dramatically upwards. The agony and distress cannot be more explicit. On both sides spectators stand gazing at the unfolding tragedy and only one of the many onlookers offer any assistance. The audience, a large group of court ladies, all react stunned while the queen, knowing that the king might be in the hazardous group, has fainted. A few ladies-in-waiting bow over her. In all this consternation, the musicians have not stopped playing. In the alcove just under the musician’s balcony, Nantouillet, the sole survivor besides Charles VI, can be seen jumping into the tub.

The king, contrary to the illuminations in the previous blog, is not protected by the Duchess de Berry’s gown. Rather, he stands upright, disorientated, gaping at the fellow performers. This ‘naked’ king, stripped of his regal robes, seems incapable of assuming his responsibilities. It is obvious that the artist has drawn a mentally unstable king, unrefined and hesitant, making this illustration not only a pictorial representation of an inconceivable tragedy but also a satirical criticism of the king himself. This idea is further emphasized by displaying the king as a wild-man, which, with a little imagination, brings a simian to mind. In the Middle-Ages simians were considered devilish creatures, representing sinful and lustful behaviour. The monkey analogy is taken a step further; it is no coincidence that the marginalia, surrounding this particular illumination, is decorated with six monkeys playing music, performing handstands and presenting other trivial tricks.

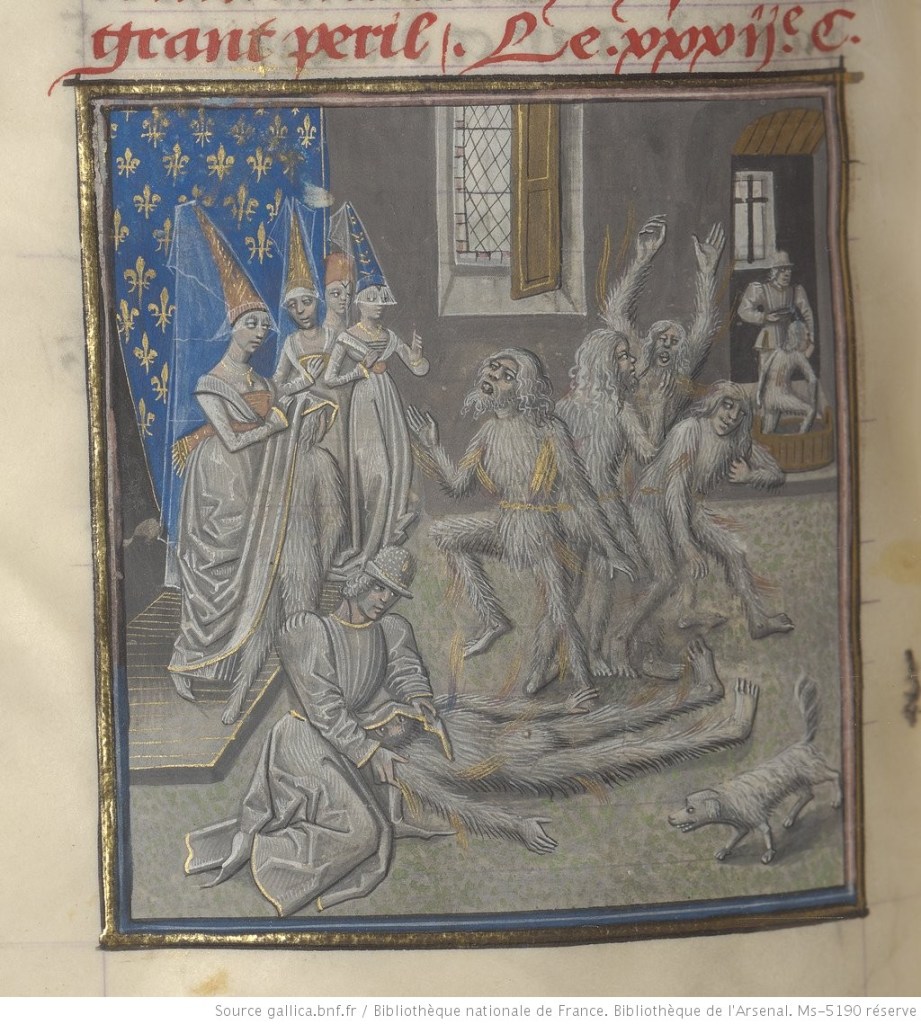

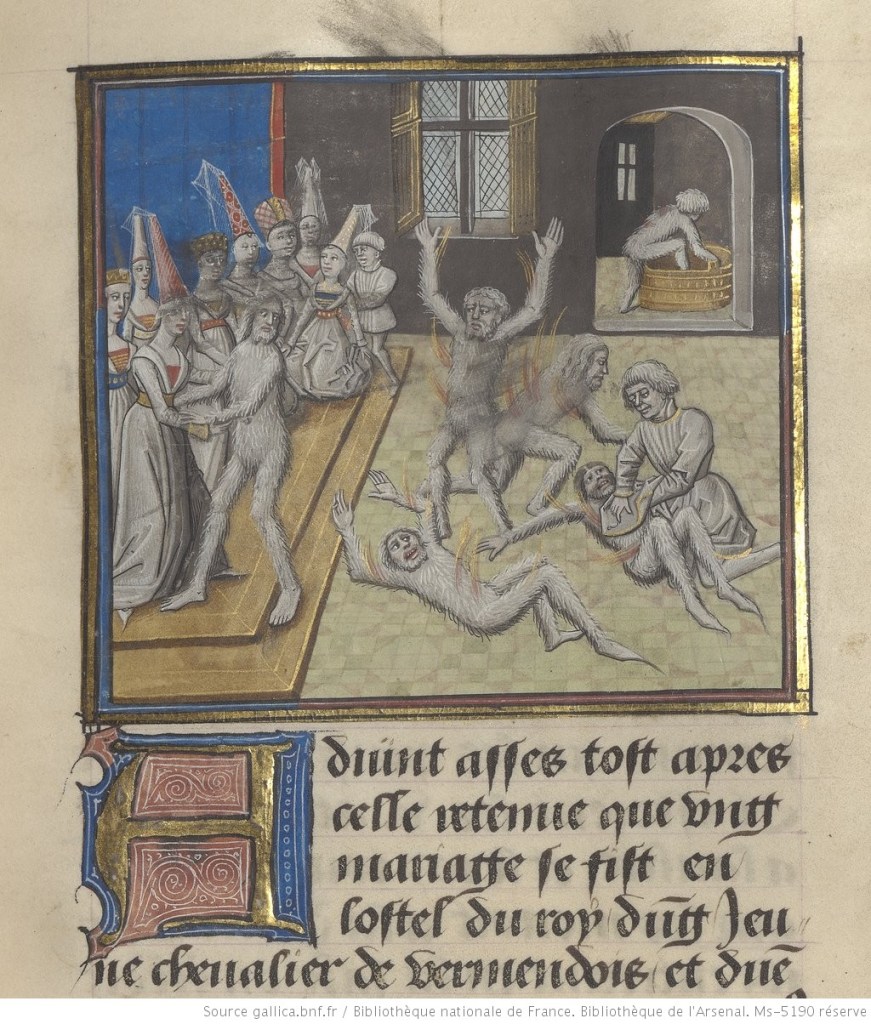

Book IV, Ms-5190, of the Froissarts Chroniques, held at Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal is a large manuscript containing few illuminations; one half page coloured illumination and eight smaller ones. All the more exceptional that two of these illuminations are devoted to illustrating Le Bal des Ardents. Both are small illuminations, just a third of a column and follow each other on consecutive pages. Both illuminations illustrate the same subject, at the same moment in time. Yet the differences outweigh the similarities. The setting, the windows, the alcove, the floor, the walls, the platform and the decorations are all different. More confusing is that folio 164v shows seven dancers and in the other illumination, there are only six. And even more noteworthy is that the king is shown hiding under the duchess’s skirt in the first illumination, while folio 165r shows the king standing upright. The dancers, seen on folio 164v, are connected by a clearly visible gold chain, yet in the second illumination there is no chain to be seen. It is baffling that two different interpretations of the same narrative should appear in one manuscript, let alone that they are placed practically next to each other.

The content of the above illuminations needs no explanation. All the familiar personages and elements are present; the king, the duchess, the flames and the tub. The guests, the musicians and ornamental background have been omitted. The artist or artists have chosen to only paint the main figures giving the reader a gripping close-up view. Except for a blue wall there is very little use of colour. In their simplicity, these grisaille illuminations, having rid themselves of decorative excesses show each personage from nearby, ensuring that the fully defined facial expressions can be seen in great detail. In comparison to the previous illuminations, where faces have been obscure, these dancers are recognizable individuals, whose body language and distressing expression make these illuminations, dramatically painful.

As so often in illuminated manuscripts, it is challenging to identify the artist. A comparison between the illuminations, shown above, might give some insight. On the left I have cropped the Breslau eliminating the townscape and some extra characters waiting under the arches. The similarities become evident. On the left, Charles VI is seen walking away from the fire, holding the Duchess de Berry. He turns to look at his companions, but makes no effort to help. Where in the Breslau the standing dancer reaches upwards, in the Arsenal a comparative figure looks desperate, but in vain, in the direction of the king. The man carrying the torch does not appear in the Arsenal version, but both illuminations show two men lying on the floor and one being helped by an attendant. The queen swoons in both and the nobleman Nantouillet is seen stepping into the tub. The earlier Breslau Froissart, made in 1468-9 was illustrated in Loyset Liédet’s workshop. This manuscript served as a model for the Arsenal. The anonymous artist or artists who painted the illuminations for the Arsenal will probably remain anonymous, but, the illuminations were undoubtedly produced at Liédet’s workshop in Flanders.

Lastly, the seventh and most unusual illumination illustrating Le Bal des Ardents, found in any of the Froissarts’s Chronicles. Were it not for the introductory text under the miniature, that announces that the following account is about a dance performance in Paris, with men resembling hommes sauvages and where a king was in great peril, you could easily mistake this illumination for a very different narrative.

Instead of the customary furry-clad wild men, this illumination has four figures, not the usual six, dressed in mid-thigh length doublets or tunics and tight-fitting hose; some even wear fashionable poulaines. Their costumes are neither tight-fitting nor covered with pitch of flax-like hair. They are, however joined together with white ribbons. Each man is easily recognizable, their faces are uncovered and each wears a unique hat; perhaps, just guessing, the man wearing a crown-like hat is the king. From a dance point of view, these men, more than in any other illumination, are indeed dancing. Taking a clue from the lifted legs and flexed feet, these figures are possibly jumping from one foot to the next. Another figure, near the opening, stands in a lunged position beckoning the other men on. The men resemble a group of dancers warming-up for their performance and not a rowdy group of wild savages, toting clubs, ready to invade the ballroom to astound their noble audience. Surprisingly, these men, contrary to Jean Froissart’s text, actually carry the torches which, as we have seen, are responsible for the impending tragedy. This illumination by William Vrelant is indeed exceptional; the essential Duchess de Berry, just as the queen, the tub, the wild men and the guests are nowhere to be seen leaving a group of enthusiastic figures unwittingly dancing towards disaster.

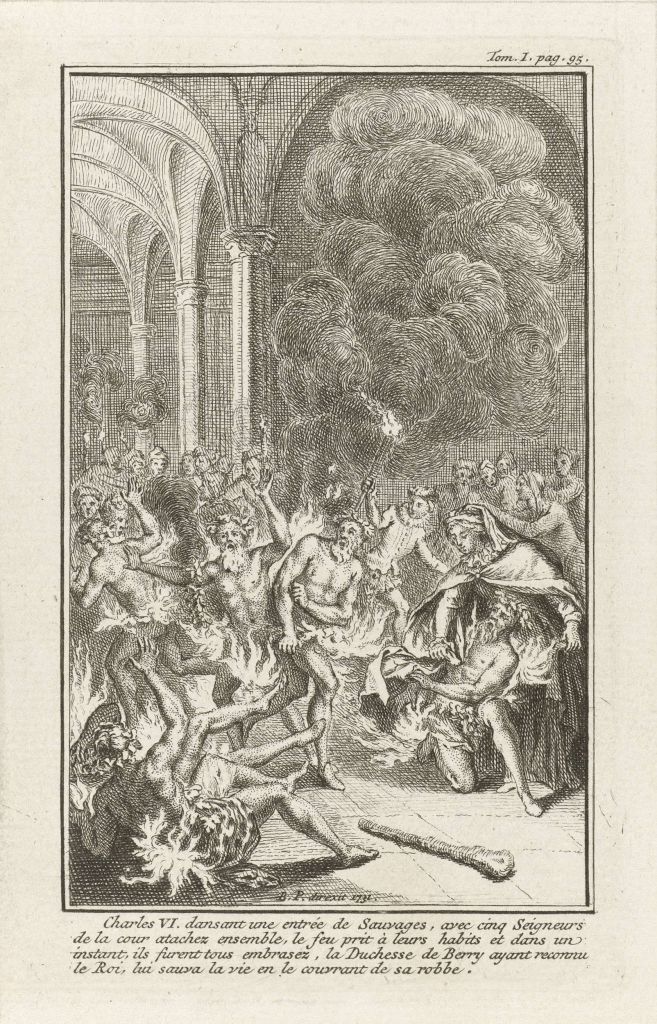

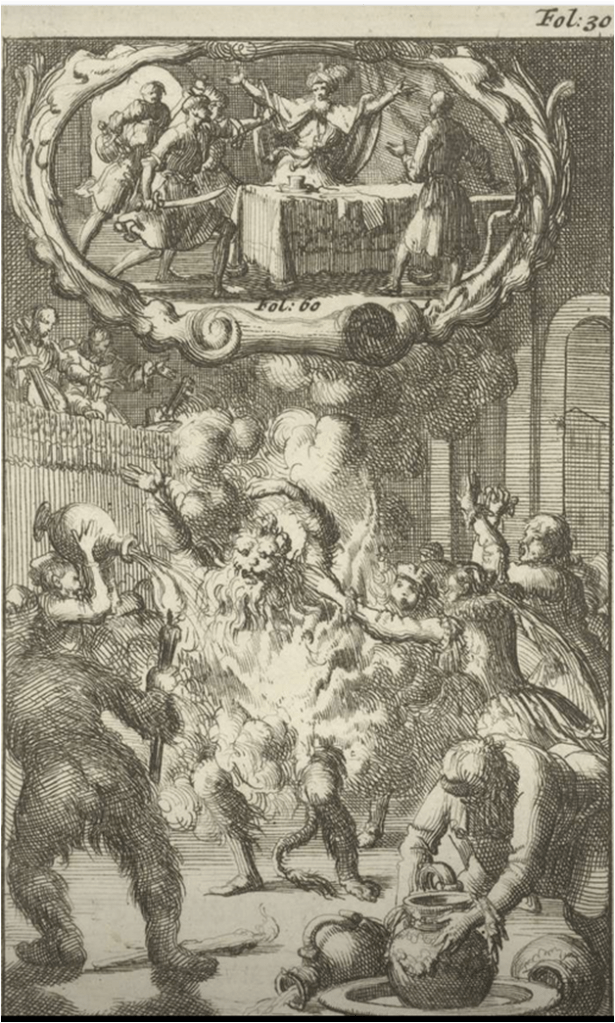

- Bal des Ardents – Bernard Picart (or workshop) – print (book illustration) – 1731 – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

- Jan Luyken – Charles VI, King of France ablaze at a masquerade/ Ablabius, murdered by command of Constantine the Great – print (book illustration) – 1687 – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

- The Remarkable Masquerade of Charles VI – Daniel Nikolaus Chodowiecki – print – 1791 – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Le Bal des Ardents remains fascinating. In the three illustrations, shown above, each artist offers an individual interpretation of the historical narrative. Bernard Picart, a French artist working in the Netherlands, shows the Duchess de Berry comforting the king with her cape, but, contrary to Froissart’s account, the king is victim to the flames. The Dutch artist Jan Luyken has drawn a wild beast, his tail hanging on the floor, completely enclosed in flames. This horrendous scene, not only comments on Charles VI but draws political allusions with the execution of Flavius Ablabius, a high official of the Roman Empire. And finally, I have chosen a print, drawn by the German artist Daniel Chodowiecki, which has both Dutch and French text. It shows a naked man, perhaps the king, enclosed by flames approaching two impeccably dressed 18th century ladies, clustered together in fear. All three illustrations send shivers down my spine.

I cannot resist closing this post with a photograph that I happened to find on the internet; street art inspired by the figures taken from Harley Froissart BL 4380 ( see previous post). Dancers of that ill-fated feast, painted by an urban artist, present themselves on the wall of a Parisian street named after the French journalist, art critic, historian, and novelist Gustave Geffroy. Le Bal des Ardents has never lost its fascination; need I say more?

1 – Lincoln Kirstein – The Book of the Dance 1942 – translation of Jean Froissart’s Chronicles p.115-116