Some of the most radiant arts works of the 15th century are to be found in illuminated manuscripts. These exquisite books were treasured and have been meticulously conserved. They, contrary to many medieval and renaissance art works, have retained their original brilliance. Whether devotional or secular, these manuscripts commissioned by wealthy patrons, are artistic gems.

A Book of Hours is a devotional book for laymen. Each manuscript was tailored to meet the requirements and wishes of the client. Thousands were commissioned ranging from the most precious, with illuminations on each page to less costly, simpler versions with just a few decorations. Although no two manuscripts are alike, the structure follows a fairly set pattern, each containing, among other sections, a calendar, prayers to various saints, an Office of the Dead and always The Hours of the Virgin which is divided in eight canonical hours. Dance images appear every so often in these manuscripts; occasionally in the calendar, sometimes in the suffrage section (prayers to the saints), but most often, in The Hours of the Virgin, accompanying the canonical hour prime (first hour) and terce (third hour). The most common illumination to accompany prime is the Nativity scene and terce is customarily introduced by an illumination of the annunciation to the shepherds. Now and again dancing peasants and shepherds surface in these illuminations.

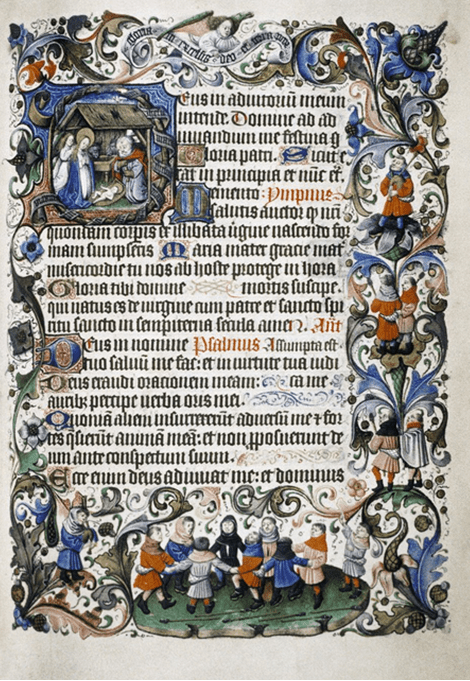

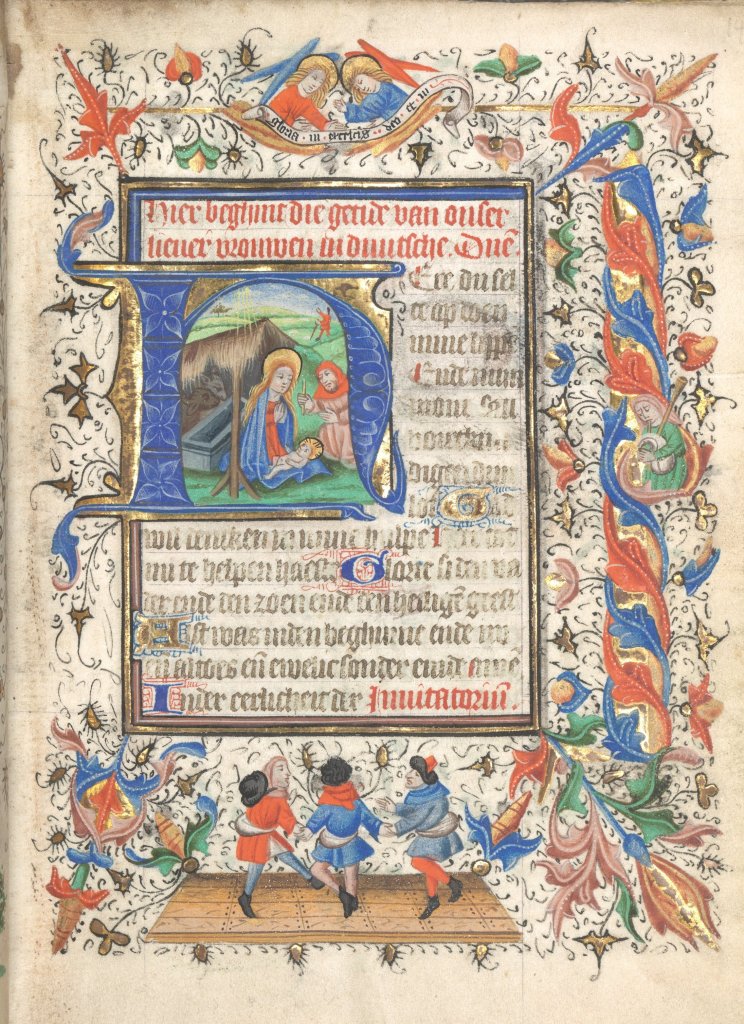

The two illustrations above show a small miniature of the Nativity scene with the Virgin Mary, Joseph and baby Jesus resting in the manger. The borders are skillfully decorated with plants, vines, flowers as well as peasants, musicians, and angels. In both cases there is a group of peasant dancers at the bottom of the page, the so-called bas-de-page. In the 14th century book of hours, dancers were usually portrayed as tumblers, as lovely ladies in graceful poises, as line endings or as hybrids. The illuminations were so rich in fantasy that realistic images became highly improbable. But, as you can see in the above folios, change was on the horizon.

The Book of Hours, known as Douce 93, with illuminations attributed to the Master of Gijsbrecht van Brederode, was commissioned by Dutch nobleman Reinoud II van Brederode (1415-1473) for his wife Yolande de Lalaing. Page after page is filled with full-page miniatures, decorated initials and extensive border decorations. The group of shepherds, shown above, overjoyed on having just heard the angel’s glorious message, have burst into dance. The Master of Gijsbrecht van Brederode has portrayed them in contemporary dress, sturdy boots and some have purses attached to their sides. It is obvious that these shepherds, their staffs lying on the ground, are dancing an improvised circle dance. Accompanying them is a musician playing the bagpipes, the instrument most commonly associated with shepherds. These shepherds, though still resembling figures from a story book illustration, have a somewhat credible appearance. I am not saying that the dancers are actually true to life figures, but they are definitely more realistic than their counterparts in earlier illuminated manuscripts.

As the 15th century unfolded art in the Low Countries exchanged medieval fantasy and reasoning for a more naturalistic approach. Realism, and painstaking attention to realistic detail, just consider the works Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden, would become distinctive features of early Netherlandish art.

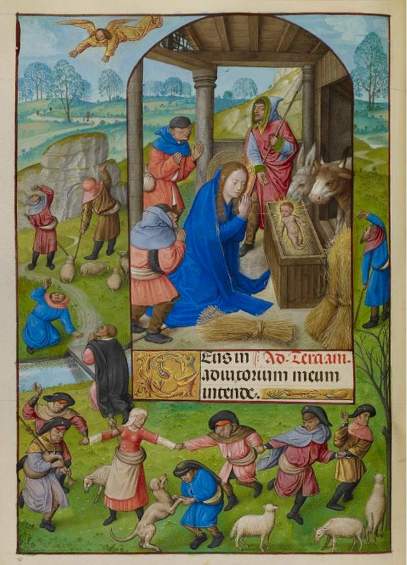

The Nativity scenes shown above, that stem from two of the most luxurious manuscripts of the early Renaissance, are full page folios, consisting of a large miniature surrounded by a biblical-story border on three sides. Common to both illuminations, is the beautifully accomplished background with trees emerging in the hilly landscape or, as in the Book of Hours of James IV of Scotland, a castle and a city drawn in fastidious detail. The background is naturalistic, if you can disregard the angels, just as the borders surrounding the miniature of the Nativity scene, which are decorated with peasants working, dogs, sheep and shepherds playing the bagpipes and dancing. The Spinola Hours, illuminated by various artists including the Master of James IV of Scotland, was probably created for Margaret of Austria and The Book of Hours of James IV of Scotland, was originally an extravagant marriage gift from the Scottish King James IV to his teenage bride Margaret Tudor, the eldest sister of Henry VIII. The Master of James IV of Scotland, generally attributed as illuminator of The Book of Hours of James IV of Scotland, is tentatively identified with the Flemish artist, Gerard Horenbout. He was court painter to Margaret of Austria before moving to the court of the Tudor king, Henry VIII.

The artist, of this playful group, must have watched dancers and dancing with keen interest; he has drawn recognizable physical movements. The shepherd’s moves are commonplace and entirely appropriate for this impromptu dance, stepping, stamping and hopping in a spontaneous line dance. The musician, playing his bagpipes, joins in with the dancing, while another shepherd challenges his dog to a frolicking duet. Furthermore, another sign of growing realism, the artist has given each individual dancer a unique expression; even the dog has character.

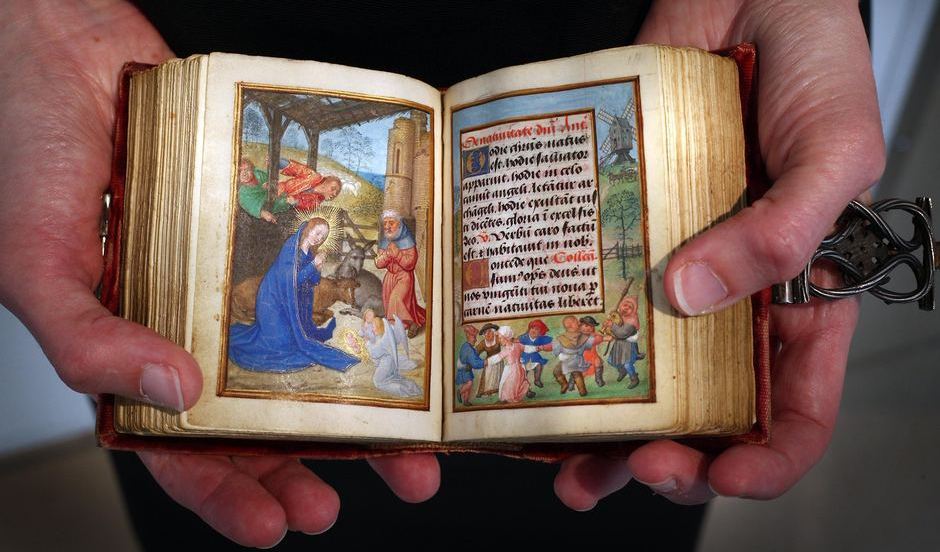

Personal prayer books were often small enough to be carried in one’s pocket. The tiny Imhof Prayerbook, commissioned by the spice merchant, Hans Imhof, is an early work of master illuminator Simon Bening. The dance scene, a group of shepherds dancing to the melody of a very sprightly bagpiper, is opposite a full page miniature of the Nativity scene. Bening’s lively shepherds, are hopping, skipping and moving quickly round in circles. The shepherdess in pink and the man on her right spur the dancers on. And at the top of the page Bening has included a traditional windmill, a customary sight in the Low Countries.

The word ‘magnificent’ barely does justice to the Rothschild Prayerbook, a manuscript illuminated by various artists of the Ghent-Bruges school including Gerard Horenbout and Simon Bening. This early 16th century manuscript, now on display at the National Library of Australia, contains sixty-seven full-page miniatures; each one a renaissance jewel. The borders are decorated with an astonishing variety of flowers, insects, butterflies and other objects; all realistically, not to mention flawlessly drawn. The only dancing figures in this manuscript appear on the folio opposite to the Nativity scene. The artist depicts a group of shepherds, who having just heard the angel’s message, join hands in a straightforward line dance. The women appear calm, perhaps spellbound, in contrast to the men who lunge sideways, stand on one leg and are overtly enthusiastic. The shepherd on the left, in the red tunic, still has his armed raised in astonishment.

I have already pointed out that realism, and a pronounced attention to realistic detail is a distinctive feature of early Netherlandish art. Realism became the norm in the production of manuscripts in the Lowlands. It was not uncommon that panel painters also illuminated manuscripts. The Book of Hours of the Blessed Virgin Mary, fondly called ‘La Flora’ complimenting the lavishly drawn marginalia full of flowers and fruit, is a rich manuscript created by some of the most famous masters of Flemish illumination. Simon Marmion, Gerard Horenbout and the Master of the Dresden Prayer Book all contributed illuminations for this manuscript made in the Valenciennes, Bruges, Ghent area somewhere between 1483 and 1489.

Allow me a moment to take a slight diversion to the ground-breaking miniature of the two shepherds, attributed to Simon Marmion. These two half-length figures are not merely realistic, but practically tangible, drawing the beholder directly into the narrative. This technique, called a dramatic close-up, is a late 15th century Flemish innovation seen both in panel painting (the works of Dieric Bouts and Hugo van der Goes) and in manuscript illuminations.

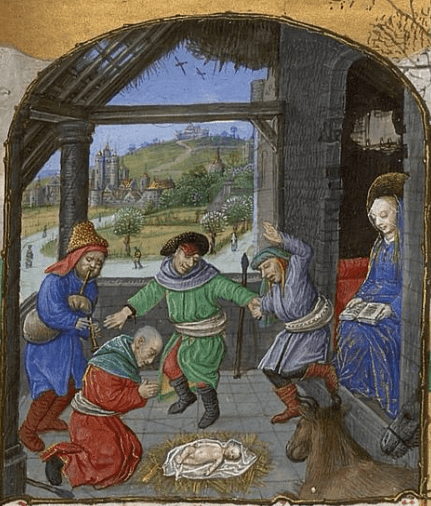

‘La Flora’ has but one dance image. On the page opposite the annunciation to the shepherds (the canonical hour terce) is one of the most unusual dance images to be found in any book of hours. The dancing shepherds are not, as customarily seen, placed at the lower end of the folio (bas-de-page) nor do they have a miniature of their own (this is the subject of the following blog) but these shepherds are actually celebrating in the manger nearby the Christ-child, while the Virgin Mary reads placidly. I have perused through many manuscripts, both from the Low Countries and the rest of Europe and this is the only example of shepherds actually making music and dancing in the same miniature as the Holy Family, which I have come across. The art of the Low Countries was known for its realism; rustic shepherds cavorting in the manger is undoubtedly, a very down to earth situation.