In one of the oldest streets in Amsterdam, stands an historic building embellished with a gable stone illustrating the Dance around the Golden Calf. This narrow street, once part of an elite neighbourhood where various mayors and the composer Jan Pieterzoon Sweelinck resided, is nowadays situated in the centre of the red light district. The gable stone, which has recently undergone meticulous restoration, shows the well-known scene from Exodus 32 where Moses returns to the Israelite camp to hear the people singing and to see them revelling and dancing around an idolatrous statue. The artist has depicted the narrative in a straightforward fashion. The golden calf, balancing on top of a pedestal, stands in the centre of the frame as musicians play for the idolaters. Moses enraged is about to demolish the Tablets of Law.

This direct presentation of the bible narrative is also found in various manuscripts. Take a look at my previous blog, Book of Exodus, for more examples. The oldest Netherlandish manuscript, that I could find, containing an image of this biblical moment, is the so-called Stavelot Bible, made in the Southern Netherlands around 1093-1097. A full-length miniature, the opening page to the Book of Genesis, presents thirty-three eventful scenes from the Old and New Testament. In the space between two roundels, a musician and dancer, representing the people of Israel, are merrymaking next to the golden calf. Moses watches the merriment from behind the calf. Directly above, captured in a roundel, Moses is seen breaking the tablets. The figures, though little more than a simple outline, are highly decorative due to the vibrant use of gilding in combination with red, blue and green hews. Especially significant is that the artist has placed the Old Testament story of Moses directly next to an image of the Crucifixion; Moses and Jesus were both mediators between God and man.

Before moving onto panel painting, I would like to draw your attention to a unique representation of the Dance around the Golden Calf in the late Gothic church of Saint Ursula in Warmenhuizen, a town not far from the famous cheese producing town of Alkmaar. The North Nederland’s artist, Jacob van Oostsanen (1470-1533), is attributed as master of the magnificent vault paintings in the choir, showing four scenes from the Old Testament, including the golden calf and the Last Judgment. Israelites, men, women and children dance stylishly around the golden calf and Moses is shown at that most decisive moment, just before he smashes the tablets. Similar to the gable stone, the tents of the Israelites form the background landscape. And to complete the narrative van Oostsanen has added two figures at the top of the mountain, next to the rib; God can be seen handing Tablets of Law to Moses.

And then there is the dancing; these dancers possess a spirited flair for movement as if they are actually, approaching each other. The three men, who partially surround Moses, thrust their hips suggestively forward, bend through their knees and use their arms ornately. They are poised, handsome and extremely well-dressed; van Oostsanen has even drawn fancy buckles or pompoms on the front dancer’s sandals. Their clothing is gracefully draped; the sleeves and accessories are reminiscent of aristocratic dress. Especially delightful are the two dancing children, nude, except for their not all too prudent, chiffon-like covering. They are lively, vibrant and looking at the upper boy, rather cheeky. Moses too, even after forty days and nights on the mountain, is immaculately dressed; the decorative embroidery on his sleeves is intricate. Unquestionably graceful, or perhaps downright alluring, is the very aristocratic lady standing near the musicians. Her free-flying scarves and floating skirt reveal that she is moving her hips to and fro, as she shamelessly displays all her feminine charms. The dancing idolaters are openly inviting lasciviousness (luxuria), one of the seven deadly sins. Van Oostsanen’s painting is a clear message for every member of the congregation; near the dance around the golden calf, hovers an unnerving painting of the Last Judgment.

Lucas van Leyden (1494-1533), a contemporary of van Oostsanen takes a slightly different approach. He, in his Triptych with the Dance around the Golden Calf (c.1530), emphasizes the feasting Israelites. He places the actual idolatrous dancing into the background. Moses can still be seen; a tiny figure on top of the mountain and one of the two smaller figures walking down the mountain ridge. Van Leyden thrusts his viewer instantly into an exorbitant banquet with fashionably clothed figures feasting, indulging and drinking excessively. Erotic symbolism such as swords, vessels, stick and tankards complete the picture. Van Leyden has highlighted the woman in blue wearing a large oriental hat. She reaches out to the man holding the empty tankard. Their behaviour, like the behaviour of the other characters, discloses that van Leyden has painted a secular world; one where all present is guilty of ‘luxuria’.

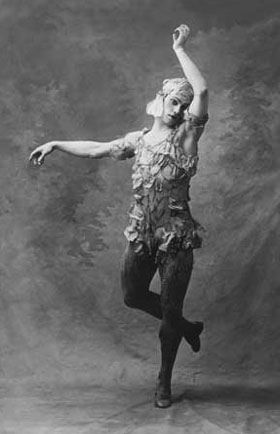

Van Leyden has banished the biblical story to the background. The dance plays a less prominent role. Not only are the dancing figures small, they are not detailed, have an anonymous character and are painted in pastel and subdued colours. Where the colour red is predominant in the front group, the receding group has to be satisfied with earthly shades of brown and muffled greens. Van Leyden depicts two types of dancing. To the right of the trees, a group of indistinct figures occupy themselves in a circular dance, and just off-centre, near a somewhat small golden calf raised on an oversized pedestal, couples run, dash and scamper or otherwise dance enthusiastically. The musicians are nearby, perched on a hillock. I especially like the vaguely drawn couple just behind the idol, who appear to delight in a type of stepping and hopping action. And at the right, a contemplative figure has taken on a position which, curiously enough resembles, the great Russian dancer Vaslav Nijinsky in ‘Le Spectre de la Rose’.

Lucas van Leyden’s composition, where the biblical story is moved to the back and the secular world is placed in the foreground is a distinctive feature of Netherlandish art. Artists outside the Low Countries tend to favour a more literal presentation of the biblical tale; Moses, the golden calf and the ecstatic dance firmly placed in the foreground. The works of François Perrier, Nicolas Poussin, Claude Lorrain and Giuseppe Gambarini are but a few examples. A number of Dutch artists, including Karel van Mander, followed van Leyden’s model. Van Mander places the emphasis is on the feasting company on either side of the painting. These Israelites are splendidly dressed. They, even though they have just crossed the Red Sea, have managed to save their magnificent hats, shining diadems, decorative pitchers and baroque glassware. Similar to van Leyden, the women are predominant; at the far right an impudent lady, apparently amused by her suitor’s advances, looks towards us with an ambiguous gleefulness. In the vista between the trees, way back in the landscape, far behind the feasting party, Israelites are gathering around the golden idol. Are they dancing or has van Mander painted a large group of people encircling the idol? Except for five people dashing, to join in with the festivities, all the dancers are indistinguishable. Van Mander gives us no indication as to how these Israelites dance. All we see is a large crowd interlacing and spiralling; van Mander has only given the suggestion of dance and totally avoided painting actual dancing. His version of The Dance around the Golden Calf is not primarily a biblical painting. Rather, in a country, that, during his lifetime was undergoing religious reform and seeing a growth in the Protestant population, van Mander offers a mirror inviting self reflection.

If van Mander invited self-reflection, the following painting by Anthonie Palamedesz (Delft 1601-1673) is without doubt social criticism. Palamedesz, a prolific artist specialized in elegant companies and portraits. A biblical narrative, as shown below, is unique in his oeuvre. All the elements of the Exodus story are present, including not one, but two dance sections. The first, the dance around the calf, immediately catches your eye. These Israelities, now dressed in shabby clothes, pray, kneel and raise their arms in adoration whilst cavorting around the idol. And between the trees, groups of people are frolicking, hopping and skipping around crunched figures. But the subject matter is not the dancing; rather the issue is to scrutinize the over indulgent individuals resting languidly in front of the trees. Like van Leyden and van Mander, Palamedesz has situated a pompously clad woman, nurturing a child, in the foreground. Her discouraging glance is focused straight at us. Behind her stands an old shrew, displaying erotic symbols, complete with a distinct feather in her cap. Feathers, decorative as they are, are also indication of absence of chastity. And then there is the drinking, the gluttony and the squandering. In Palamedsz’s hands, the dance is merely a prop to expose the excesses of a forlorn society.

Jan Steen (Leiden 1626-1679) one of the greatest story tellers of Dutch art, continues the van Leyden tradition. His Golden Calf includes an idol, lots of dancing Israelites, Aaron and a large group is misguided people guilty of the mortal sins; lust, gluttony and perhaps even greed and pride. Moses makes no appearance in this painting but the women in blue silk, whose beguiling glance cannot be misinterpreted, is eye-catching. The dance scene, placed in the background, plays but a minor role; the golden calf plus dancers are barely larger than the lavishly sunlit woman suggestively handling an open copper vessel. Notwithstanding their size, Jan Steen’s barefoot dancers with their heads tilted upwards, their animated leg movements, their twisted torsos are absolutely convincing. These rapturous Israelites are worshipping the idol with unrelenting conviction; Jan Steen has captured, as no other, the frenzy of an ecstatic bacchanal.

The Dance around the Golden Calf whether portrayed as biblical narrative or as social criticism remained a popular subject for many centuries. To give an idea of the numerous artists that addressed the subject, I have selected five artworks. These and the many others, not mentioned, are compelling and well worth our attention.

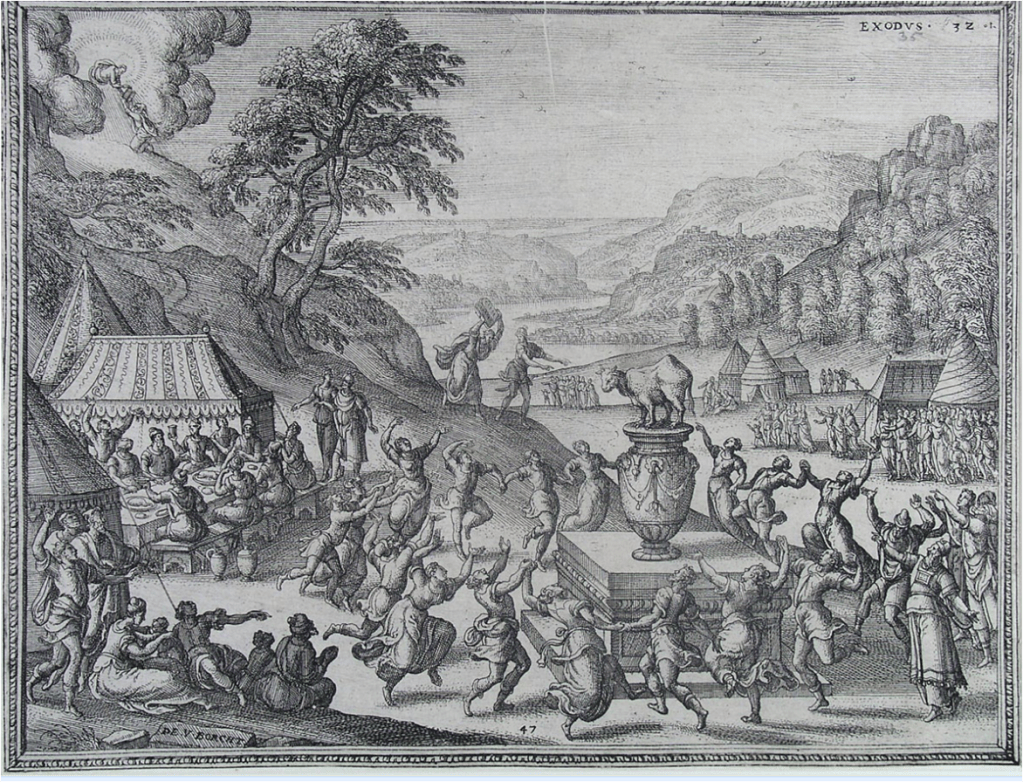

- Worship of the Golden Calf – engraver Pieter van der Borcht – 1582-85 – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

- Israelites dancing around the Golden Calf – design c.1566 – after Maerten van Heemskerck – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

- The Golden Calf – Pieter Pourbus – 1550’s- National Gallery of Ireland

- Worship of the Golden Calf – Frans Francken II – Museum Rockoxhuis, Antwerp

- The Adoration of the Golden Calf – attributed to Jacob Willemsz. de Wet – formerly collection Gavnö Castle, Denmark