In the central panel of the triptych The Temptation of Saint Anthony, stands the ruins of a tower; the top tier shows the hand of God handing the Tablets of Law to Moses and immediately below are the most extraordinary dance figures in all of Bosch’s paintings. Bosch has painted, as if in low relief, four totally original figures; one stretches outwards with all his might, two others bend or stoop and yet another twists and rotates beholding the idolatrous image resting on the mound. Their broad, sweeping movements seem neither to have a pattern nor a structure, as if improvised intuitively in the exhilaration of the moment. These bizarre dancers move in a moresca-like style. Bosch has knowingly chosen a Moorish dance to illustrate a seminal biblical episode from Exodus.

Moresca dancers, jesters and musicians were entertainers dancing in the villages and at court. Even though the moresca performance often represented a mock combat, there was no hidden message. The moresca-like dancers that Bosch painted in The Temptation of Saint Anthony, like so many other images that he painted, represented more than meets the eye. Dance, in the age of Bosch, was considered lewd and lascivious; a corruption of the Christian soul. Consequently, when Bosch painted dance images he had a definite, moralistic purpose.

On the ruins of the tower, Bosch illustrates various scenes, including the consequential Old Testament moment in the book of Exodus, when Moses on his return from Mount Sinai sees the people of Israel dancing around a golden pagan idol. Bosch aligns this moment directly with a candlelit image of Christ on the cross. Christ, pointing to the crucifix, stands in the shadowy background; a marked difference to the brightly lit dancers and other figures on the remnants of the tower. Bosch contrasts the true image of God against the idolatrous children of Israel dancing around false gods; he juxtaposes a pivotal moment in the Old Testament against an equally crucial moment in the New Testament. This depraved dance in Exodus warns against the violation of the first and second commandment; dance becomes a metaphor for heretics, pagans and therefore for idolatry. Bosch then advances the thought even further featuring, not just any dancer, but exhibiting oriental moresca dancers as archetypes of barbaric, heathen worshipers.

Moresca-like dances were not unknown in the Low Countries. As early as 1470, members of a local actors’ association performed a frenzied dance in moresca-style around a golden calf, in the Dutch city, Bergen op Zoom. The moresca was deemed idolatrous, but remained popular, due to its overwhelming exuberance and captivating exoticism. The dance was spectacular, amusing and dancers astonished their audience with their stunning pantomime and acrobatic feats. The dancers wore curious costumes, wrapped bells around their knees and ankles and had shawls and flying ribbons attached to their costumes. Bosch must have been acquainted with the moresca dance, either having seen engravings of the dance or perhaps even, the statues made by Erasmus Grasser. Just as likely, Bosch may have seen the moresca at a town fair or at local festivities. The energy, spirit and vigor of the moresca must have appealed to the artist. His idolatrous dancers, similar to the entertainers, move dynamically, wear free-flowing robes and have ribbons soaring in varying directions. Bosch, however, gave the moresca his own specific connotation.

Hieronymus Bosch -The Temptation of Saint Anthony – Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon – c. 1501 – detail of centre panel (click to expand)

How Bosch transformed the vivacious moresca into a powerful message becomes more obvious if we compare a well-known engraving with the dancers of the Saint Anthony triptych. Comparing Israhel van Meckenem’s dancers to those by Hieronymus Bosch we find both similarities and differences. Similar to both are the exaggerated movements, full of deep, spacious lunges combined with active torso deviations. The dance, in both cases, is robust and vigorous. Bosch’s men are bare legged quite dissimilar to the theatrically costumed men encircling the young woman. The Bosch dancer with outstretched arms and fluttering bands, wears what look like a skirt comprised of ribbons. All the men have some type of head-gear. Their movements appear similar but their expression and motivation are worlds apart. Where van Meckenem’s engraving shows a group of entertainers dancing around the lady in, what appears to be, a rehearsed choreographic setting, Bosch’s figures dance passionately, instinctively, without music, totally engrossed in unwavering adulation. Their dramatic dance is born of internal conviction, driven by religious determination.

The central panel of the Prado triptych, The Adoration of the Magi, also called The Epiphany shows the three Magi bringing gifts to the Virgin Mary and Child. The three sages, who traditionally hail from the East, were once worshipers of other gods. They now come in adoration to the one true God. Caspar and Melchior are kneeling in reverence, in close vicinity to Christ. Only Balthazar, the Moor, remains standing. He stands at the outer edge of the panel. This tall, majestic man, beautifully dressed in utterly handsome eastern robes, tentatively keeps his distance. In the background, between him and the other Magi stands an enigmatic figure about whose identity and significance art experts still deliberate to this very day.

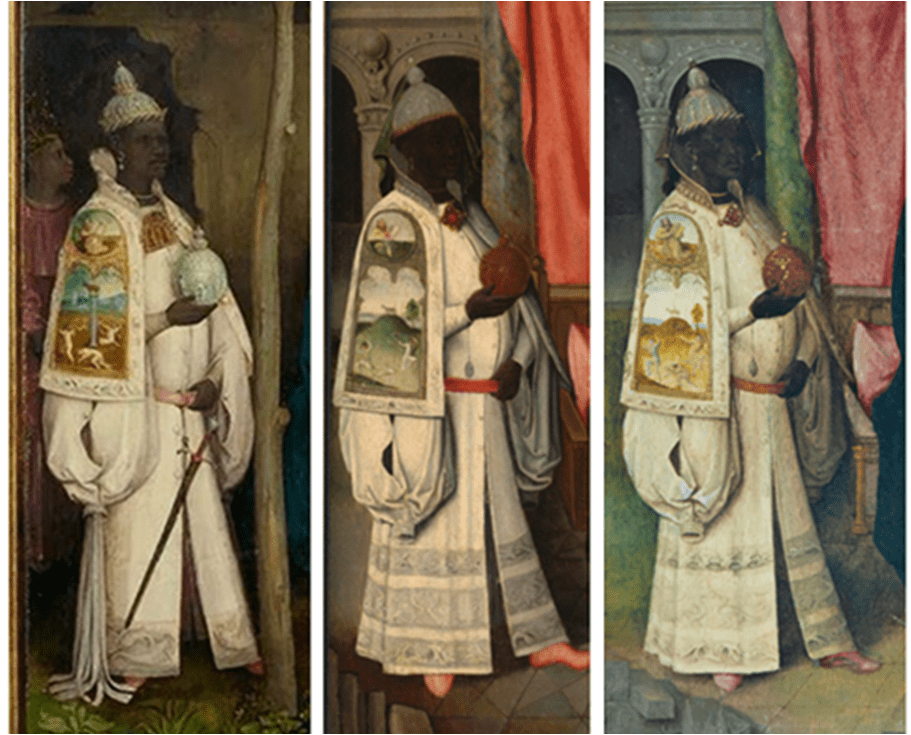

The works of Hieronymus Bosch were in great demand and many copies were made either by artists in his own workshop or by his followers. The Adoration of the Magi was frequently copied; sometimes as a triptych and sometimes, only the central panel. The copied paintings closely resembled the original, retaining the predominant figures of the Virgin Mary and Child and naturally the three Magi. The setting and positioning of the figures were changed or rearranged from painting to painting, especially in regard to the landscape, the architecture, the extra figures and the animals. The noble Moor, however, remained constant. All copies show the dignified Moor standing, the furthest away from the Virgin and Child, near the left edge of the central panel, splendidly attired in off-white apparel with voluminous sleeves. In at least three known copies, possibly inspired from a lost Bosch original, we are reminded of Balthazar’s once idolatrous past. In each case Balthazar, bearing the gift of myrrh, has the Dance around the Golden Calf copiously embroidered on his sleeve.

Balthazar’s sleeve displays the same Old Testament scene as painted on the ruins in The Temptation of Saint Anthony; the Dance around the Golden Calf. In a wild, barbarous frenzy, three nude men run, jump and leap with relentless gusto; one man falls or dives to the ground in overpowering earnest. Why does the Moor, coming in adoration of the newborn Christ Child, have a decoration on his sleeve that illustrates a false Jewish idol? These dancers, just as in the Saint Anthony triptych, move in a characteristic moresca style with ribbons fluttering freely. A strange combination; moresca dancers that are encircling a false god, embroidered on the sleeve of a Magus, who himself was once idolatrous. That Bosch and his followers have juxtaposed three idolatrous moresca dancers against the three exotic Magi may be more than a coincidence. It is possible that Bosch, is reminding the onlooker of the previous idolatrous existence of these powerful men from the East; and he may be questioning their conviction.

- Hieronymus Bosch – The Adoration of the Magi – detail – Museo del Prado, Madrid

- Follower Hieronymus Bosch – detail of sleeve – Erasmushouse Museum, Brussels ( Anderlecht)

- Circle of Hieronymus Bosch – detail of sleeve – private collection – Christie’s

- Follower of Hieronymus Bosch – detail of sleeve – Noord Brabantsmuseum – Moonentriptych

- Click on each image for an enlarged view

Every Bosch painting is a journey of exploration. Besides the moresca, Bosch painted peasant dancers, curious dancers, hybrid dancers and the dance of death. Bosch, a devout man believed that secular music, as popular dance, led to perdition. Musicians and dancers were condemned; souls that needed to be punished. Dance, for Bosch, was a tool to express admonishment in the hope of enlightening those who strayed away from the moral path.