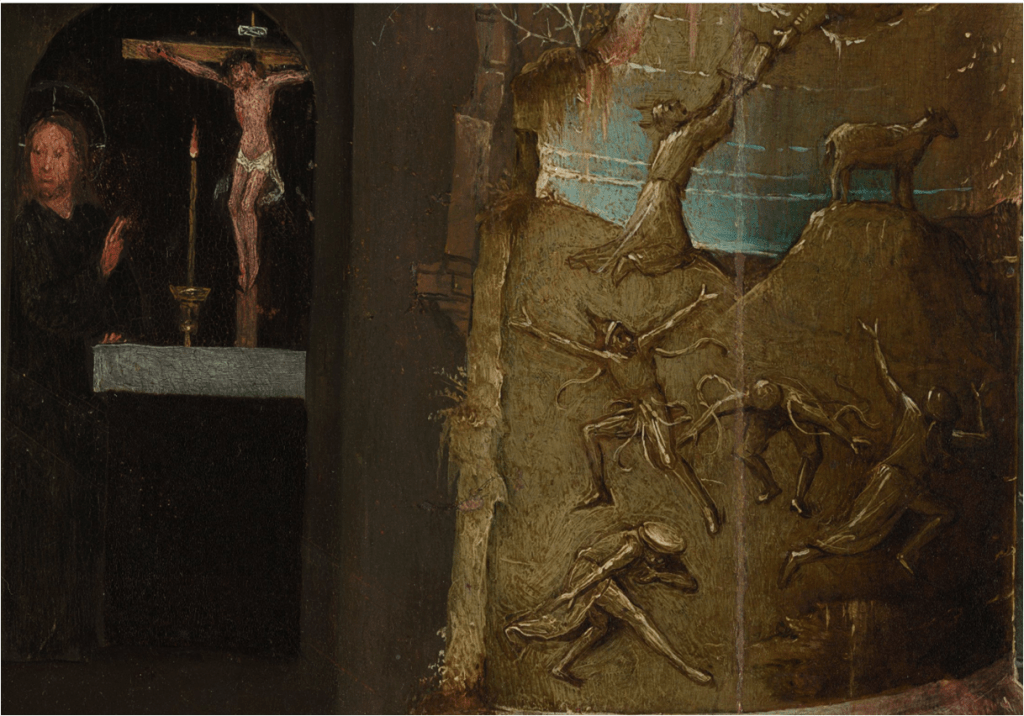

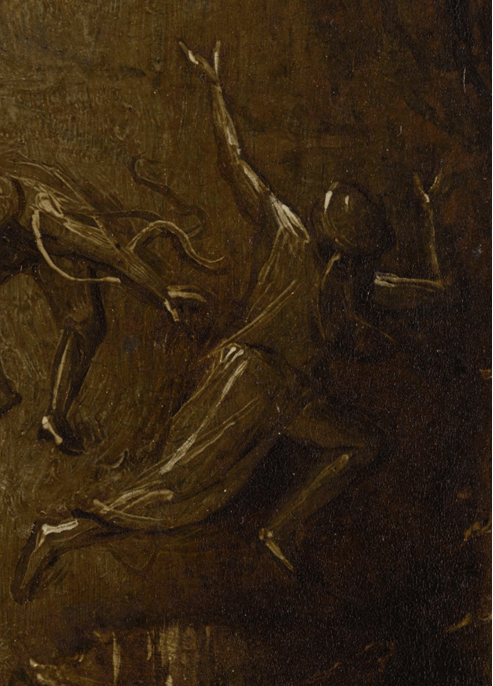

In the central panel of The Temptation of Saint Anthony, a triptych by Hieronymus Bosch stands the ruins of a tall tower. This tower is divided into four tiers; the top tier shows the hand of God handing the tablets, the Ten Commandments, to Moses and immediately there under are the most stunning dance figures in all of Bosch’s paintings. Four exotic dancers fling themselves into amazing movements with zest and dynamism. These moresca dancers whirl, stretch, bend their torsos and rotate their shoulders in a frenzy at the foot of an adjoining mound. Exhilarated they perform their idolatrous dance around the heathen god, the golden calf, with inexhaustible abandon.

The moresca was a popular dance form in many European countries from the 15th to the 17th century. It was never a social dance, but a danced pantomime performed at fairs or at court. There is much uncertainty about the origins, although most experts agree that it originated in Southern Spain and travelled from there to Northern Europe. The dance often represented a mock combat; possibly a theatrical re-enactment of the conflicts between the Moors and Spanish during the Reconquista. The performance was highly energetic. Dancers were known to wear bells around knees and ankles, clash sticks, wave handkerchiefs and disguise themselves, at times, even blackening their faces. The moresca was mostly danced by six or eight men together with a jester, a fair lady or a man dressed in women’s clothing. Just for the record, there is another dance form with a very similar name: morris dancing. The moresca and morris dancing most probably have the same roots, have many of the same elements, but they have evolved as two very different dance forms. The moresca has long lost its popularity while morris dancing, especially in the British Isles, is thriving to this very day.

Bosch’s moresca dancers are fascinating. No other Netherlandish painter, of his time, ever painted such unorthodox dancers. In Italy, Renaissance artists, created magnificent art works where courtly ladies, angels and heavenly souls danced in the most pleasing formations. In Sandro Botticelli’s The Mystical Nativity, painted at approximately the same time as Bosch’s Temptation of Saint Anthony, celestial angels grace the heavens. Likewise, in the work of Andrea Mantegna, Giulio Romano, Benozzo Gozzoli among others, the dancers, very often women, gently draped in Grecian-like chiffon’s or fashionable court dress, are delicate, lofty beings displaying perfect elegance. Bosch’s rowdy, thoroughly grounded moresca dancers are the direct opposite.

Where did Bosch find the inspiration and the knowledge to portray the moresca dancers with such a degree of accuracy? He appears to understand the physical sensation and the dynamics of the movements. No documentation has survived to suggest that Bosch ever had any contact with the moresca , so the question remains how Bosch became acquainted with the moresca way of dancing? This is not a question that I can answer, or that can be answered. All the more intriguing to look at 15th century moresca dance and dance images, known in the Low Countries, and to speculate if these may have inspired Hieronymus Bosch.

The earliest known illustration of the moresca can be found in the National Library of the Netherlands; the History Bible, created in Utrecht in 1443. In the margin surrounding a miniature of David defeating Goliath and a historiated initial of David playing the harp, a group moresca entertainers, comprising of two male dancers, a jester, a female dancer, a monkey suspended on a pole and a musician, perform. These dancers show none of the highly stylized movements that Bosch will eventually use, but they definitely look exotic and the two men wear bells on their ankles and knees, and similar to the Bosch figures, have long scarves flying around him.

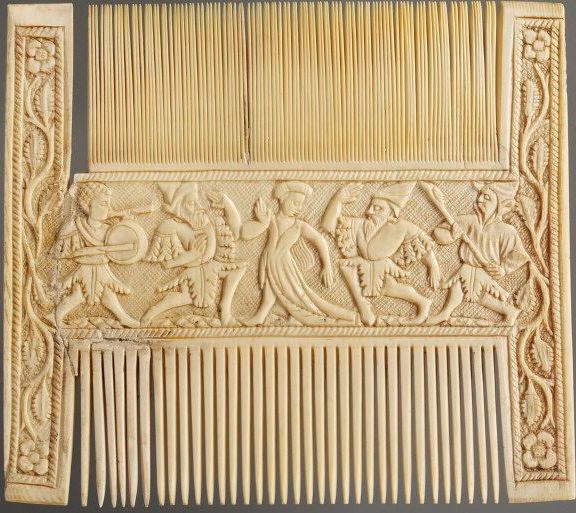

A comb, of carved elephant ivory, made in the Southern Netherlands between 1440-1470 is decorated with a group of five moresca performers. These are exotic figures dancing in an unfamiliar fashion. The movements of the two men, on either side of the lady, are exaggerated; their deep knee bends, thrust forward torso and bold hand positions make them appear quite striking. The British Museum has an ivory mirror case with a group of lively moresca dancers in their collection. These figures, similar to the ones on the comb, are exotic in appearance. They perform unrefined movements and have scarves or garlands emerging from their attire.

Barthélemy d’Eyck, an early Nederlandish painter and illustrator of illuminated manuscripts, worked in France and probably in Burgundy. Perhaps he was related to Jan van Eyck, but this is not documented. Around 1440-1450 he illustrated a Book of Hours, now at the Morgan Library & Museum, containing various moresca-like figures. One folio is especially interesting. In each corner of a folio showing a large miniature Virgin Mary and Christ Child, there are musicians and dancers wearing elaborate hats and costumes complete with scarves falling over the shoulder to waist level. These colourful figures, though less powerful than the Bosch figures, rotate, twist and bow in a novel somewhat oriental way.

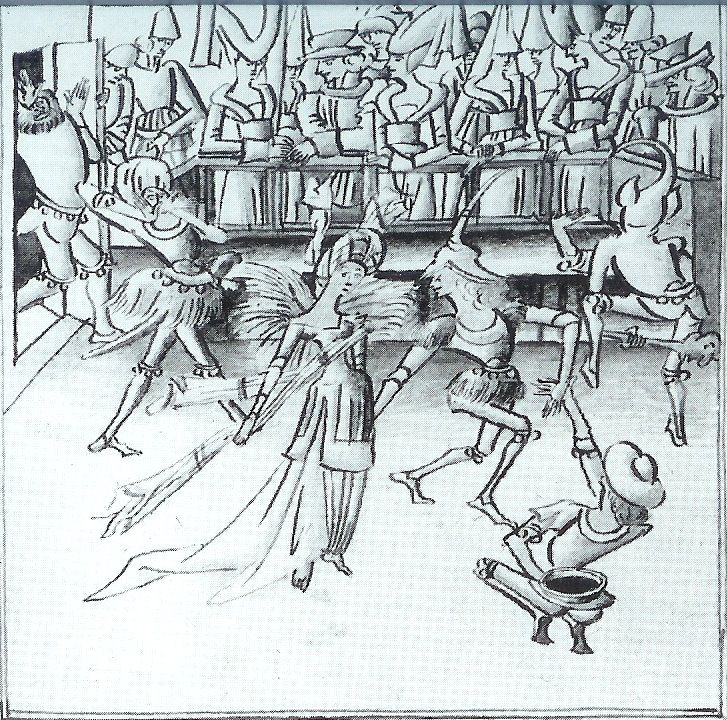

Closer to home is an illustration of a moresca performance being watched by spectators at court. The illuminator, the Master of Wavrin, worked in the vicinity of Lille. His specific style is easily recognizable; swift lines and strokes, sketched outlines, just enough detail and sparse use of colour; practically, if I may use a contemporary term, a strip book illustration.

The power and dynamics of the Master of Walvrin’s dancers give the 15th & the 16th century viewer an indication of how riveting a moresca performance could be. Take for example the front man, holding a bowl behind his back, who squats deeply, barely grabbing the hand of the man in front. That man, focusing intently at the lady, takes large strides rotating his torso and head actively. And then there is the dazzling position of the man standing behind the lady, whose legs and body are so twisted that they appear disjointed. Have you noticed that large, bulky figure stepping through the doorway? And, to top that, the jester looks as if he is trying to entertain a few disinterested court ladies. Their attire is typical of the moresca dance; the dancers have a string of bells around their waist and their knees and the beautiful lady woman, dressed in an elegant gown, carries a long scarf. The scene is festive; a moresca performance at court. How different to Bosch’s Saint Anthony where religious and moral overtones are symbolized by the exotic pagan dancers.

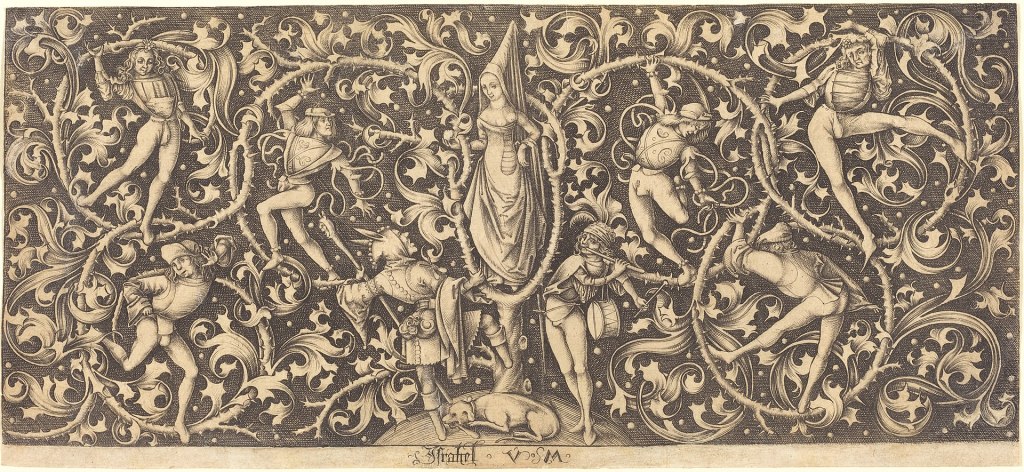

Israhel van Meckenem’s roundel is astonishing. Van Meckenem (c.1440-1503) was a goldsmith and engraver and considered to be the most prolific engraver of the fifteenth century. He was a contemporary of Hieronymus Bosch, of German birth, though his family was probably of Dutch origin. He lived and worked near the Dutch border. It is more than feasible that artists from both sides of the border influenced each other. And besides that, van Meckenem’s engravings were sold at art markets; they were readily available to all buyers.

In van Meckenem’s engraving we see villagers peering through the window, watching a group of moresca dancers. As in other images there is a jester, a musician and a lady surrounded by dancers. Two dancers, like the Bosch figures, integrate long scarves into their choreography. These two dancers are especially impressive; the man on the left, taking an oversized, unrestrained step towards the lady and the man, centre front, lunges forward in an off-balance thrust. Van Meckenem has captured the sheer dynamism of the movement, exaggerating the dancer’s actions to the point of caricature. A second engraving by Van Meckenem, shows moresca dancers and musicians, placed against a filigree background, revolving around a beautifully dressed court lady. The engraving is all the more interesting because this specific design was used as decoration of the main staircase of the University of Salamanca, Spain, in the first quarter of the 16th century. My point being that Van Meckenem’s engravings were extremely was popular, well-known and available in various countries; possibly even in Bosch’s hometown ‘s-Hertogenbosch.

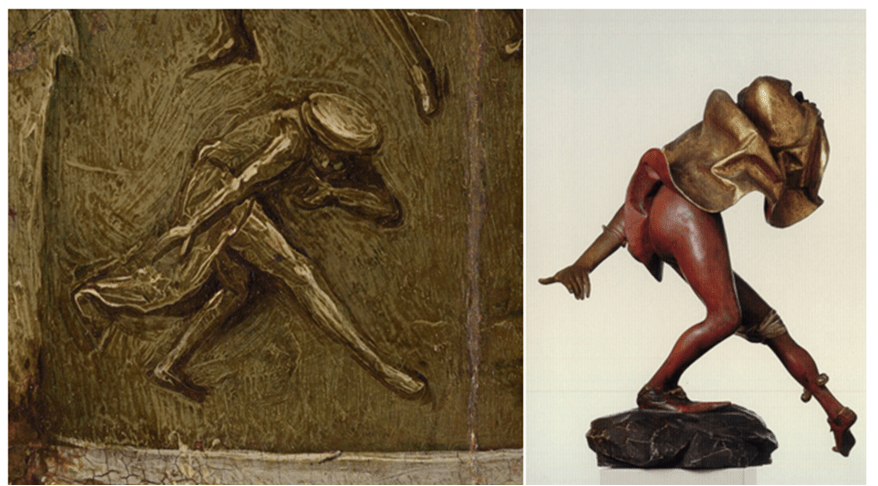

Staircase – University of Salamanca – early 16th century – photo. F. Simón.H

The dancer’s poses, in the filigree engraving, are undoubtedly lifelike. One might assume that Van Meckenem had actually seen the dancers perform. This is quite plausible; these exotic dancers, were in demand, travelling from place to place, dancing at village fairs as well as at court. Another possibility is that Van Meckenem has seen the work of the Erasmus Grasser (1450-1518) a sculptor working in Munich, who created sixteen statues of moresca dancers, of which ten still exist, to decorate the walls of the assembly hall in the Munich Town Hall. Grasser’s statues are animated and realistic. The figures use their entire body actively, twisting, rotating, bending; in fact, using all their physical capabilities creatively. They give an extraordinary insight to the complexities of their dancing and of the carefree sphere that accompanied their performances. Could Hieronymus Bosch have known Erasmus Grasser’s work? The likeness of the following illustrations is undeniable.

In Bosch’s time the moresca, whether through art or performance, was well known in the Low Countries. In fact, in 1470, in the Dutch city Bergen op Zoom, the local actors association performed, my paraphrasing, ‘a dance around the golden calf in an exotic moresca style’. No such information has been documented in ‘s-Hertogenbosch but there is always the possibility that Bosch had the opportunity of seeing the dancers at a local fair or at a religious procession.

There is an issue to be addressed. The moresca was and still is, a high-spirited form of entertainment, and yet in The Temptation of Saint Anthony, Bosch chooses a unique portrayal; the dance is no longer diverting, but laden within a Christian context. Why this alternative approach? Does the moresca feature in his other work? This I will attempt to discuss in the following post.