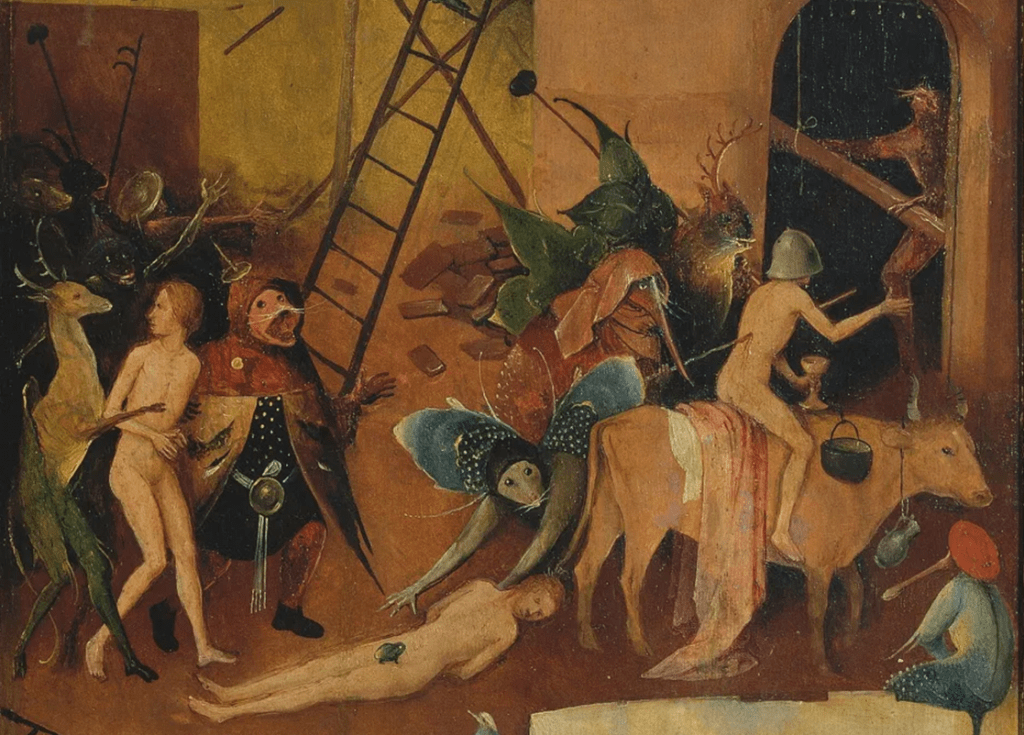

On the right panel of The Haywain and the Bruges version of The Last Judgment a strange figure, a naked soul, rides on a bovine. Perhaps, if his helmet is any indication, this soul might once have been a soldier. A lance pierces diagonally through the torso of the rider. The excruciating pain seems not to disturb him. He continues on his path relentlessly. The rear end of the bovine is covered with cloths; possibly sheets with which to bury the dead. In both paintings the figure holds a chalice, symbolizing sacrilege, and carries a cauldron. The black cauldron suggests that the figure has, in the past, ignited a fire with fatal consequences. The figure in the Last Judgment carries a long javelin draped with a white shroud-like cloth. A rooster is perched on his helmet. He pulls a wooden cart laden with a man-size cauldron. Two sinners are trapped, being boiled, in the large black pot. Behind the Haywain rider, lays a naked body whose private parts are covered by a toad. An uncanny fantasy creature with butterfly wings hurries to approach the sinner. Notwithstanding all the barbarity, the riders continue striding slowly, steadfastly through hell, surrounded by ghastly monsters, atrocious animals, hybrids, dead souls and sinners.

Bosch uses this image, the personification of Death, twice; the first time in The Last Judgment in 1486 and again in his later triptych, The Haywain painted in the early 16th century. Images of Death, especially those on horseback, were certainly not uncommon in the Middle-Ages and early Renaissance. Death was repeatedly depicted as a skeleton mounted fiercely on a horseback. Albert Dürer’s magnificent work, The Four Horsemen of The Apocalypse (1498) shows four terrifying horsemen as precursors of damnation.

One can only speculate why Bosch chose to place his rider on a bovine. Perhaps he was familiar with the illustrations of Death in Franceso Petrarca’s Triumph of Death where Death’s chariot is drawn by oxen or he may have been inspired by a popular allegorical poem, La Danse aux Aveugles, written by Pierre Michault, in 1465. The poem relates the dream of the leading personage, named L’ Acteur, who is guided by Understanding to three ballrooms and is shown the three dances that all mankind must dance in their lifetime. There Blind Love, Blind Fortune and Blind Death, ‘teach man their dance‘ until ‘in the giddy dance, his feet Lead him watchful Death to meet’. This highly moralistic poem forewarns the reader of the perils and temperaments encountered when susceptible to love, when flirting with fortune and when death approaches.

Love, Fortune, Death, blind guides by turns, Teach man their dance, with artful skill; First, from Love's treacherous wiles he learns To thread the maze, where'er he will. Then Fortune comes, whose tuneless measure Bids him whirl and wind at pleasure, Till, in the giddy dance, his feet Lead him watchful Death to meet. Thus follow all of mortal breath, The dance of Fortune, Love, and Death.

The following two miniatures of Death mounted on an ox, were painted around the same time as Bosch’s rider in The Last Judgment. Similar to the Bosch figures, the rider, a near skeleton, carries a long javelin. In both cases a long flowing white shroud is arranged over the ox’s horns. In contrast to Bosch these riders are not pierced by a lance and carry neither a chalice nor a cauldron. The sphere of the miniature is equivocal, but less fantastic, less frightening than Bosch’s awful portrayal of hell. These scenes are set in a palatial ballroom. Death takes the most prominent position in the room. Near him musicians are playing and a woman holds up a banner. It bears the name Atropos. Together with her sisters Clotho and Lachesis, Atropos formed the three goddesses of fate and destiny. Atropos, the eldest of the Fates, cuts the thread of life. The people, representing Mankind, are dancing to Death’s melody. In the left miniature the people, regardless of proximity of Death, are enjoying a circle dance whilst in the right miniature court dancers are partaking, unperturbed, in a line dance. The people appear blind to the presence of Death and, it seems, are oblivious of the threat that the Atropos banner implies. This contrasts distinctly from the Bosch paintings where Death travels in the most horrifying hell and the sinners are all too aware of his imposing presence.

We have no way of knowing if Bosch was familiar with the above illustrations, but there is a possibility that Bosch was acquainted with a translated version of Michault’s poem, printed in Gouda in 1482, a town not more than seventy kilometers from his home town ‘s-Hertogenbosch. This incunabulum, a book printed before January 1501, contains woodcuts of the three blindfolded guides. Mankind dances before the blindfolded Cupid as he stands on his dais, the crowned Queen of Fortune seated on her throne, and in the final room, the blindfolded Death.

Blind Death, in this woodcut, is undeniably similar to the figures Bosch painted. Death, in this case, blindfolded, is sitting on an ox. He, as the Bosch figure, carries a javelin in his hand. The ox has a long cloth draped over his back. On either side of Death, musicians are playing and directly behind Death, though not easily distinguishable, figures are frightened and being tormented.

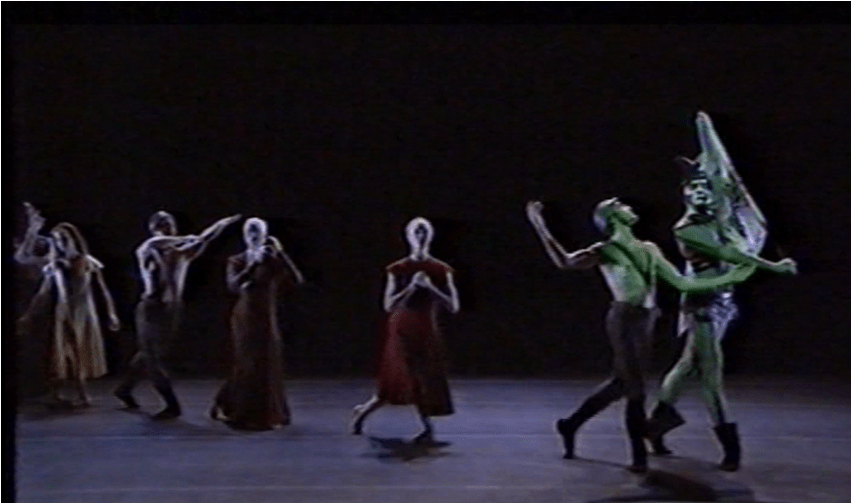

The dancers on the woodcut, despite the jovial musicians, seem to walk as if in a trance. They are dancing the Danse Macabre. In the late Middle-Ages and Renaissance, a time of plagues and great hardship, images of the Danse Macabre were commonplace on church walls, in manuscripts, woodcuts and paintings throughout Europe. Death, as these images show, approaches and harvests those who must die; young and old, rich and poor, from all walks of life. This theme has inspired musicians, painters, sculptures, writers and choreographers over the centuries. Kurt Jooss (1901-1979), the great expressionistic choreographer created a compelling dance of death in 1932. The Green Table, a tableau in eight scenes, shows death approaching and collecting the victims of a pointless war.

A very different version of the Dance Macabre was created by the Dutch choreographer Rudi van Dantzig (1933-2012) for the Amsterdam based company, the Dutch National Ballet. Van Dantzig was an idealist. His work was defined by a strong communal commitment, marked social criticism, awareness of environmental issues and a daring approach to controversial subjects. His Monument for a Dead Boy (1965), addressed homosexuality and in the 1971 production of Painted Birds, a theatrical choreography, he focused on pollution and mental deprivation in contemporary society.

In Vier Letzte Lieder, to Richard Strauss’s song cycle, van Dantzig, a highly passionate choreographer, explores intense human relationships. Through a series of touching and emotional pas de deux, the choreography follows four couples in their individual paths to accept the inevitability of death. The van Dantzig figure of death is compassionate, not unlike a benign angel. Death, a role created by Clint Farha, approaches each couple, in turn, escorting them serenely to the spiritual world.

Rudi van Dantzig could be described as a moralist; his ballets are infused with his far-reaching idealism. The statements he made and issues he addressed in his ballets were pertinent in his day, and with hindsight even more pertinent today. Van Dantzig, often in collaboration with choreographer Toer van Schayk, forced his audience to listen, to look and to respond. His ballets were not merely entertainment; they were harsh wake-up calls. So too are the works of Hieronymus Bosch. Who would not be frightened after seeing the terrors on his Hell panels? Who would not become pious to avoid his horrendous premonitions? The work of both men is preeminent. The painter Hieronymus Bosch, however, has a great advantage over the choreographer Rudi van Dantzig. Paintings, even after five hundred years, retain their impact. Choreography, however impressive, fades as time passes by.