Le Roman de la Rose is without doubt the most celebrated secular manuscript of the late Middle-Ages retaining an overwhelming popularity over a period of a few hundred years. This allegory of courtly love, tells the tale of a poet who, having fallen asleep, dreams about his quest to win his ideal love, a beloved rose. Today, there are more than three hundred extant copies to be found in libraries worldwide. Many copies are to be found in the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

This medieval poem was written in two stages; the first four thousand lines were written by Guillaume de Lorris around 1230. The second part, an additional seventeen thousand lines, was written forty-five years later, is the work of Jean de Meun. The two sections differ considerably. The first, a poem of chivalry and idealistic love, takes place within an enclosed garden where Amour shoots the poet, now called the Dreamer (or The Lover), with his arrows. The Dreamer, enraptured by the sight of a rose, is approached by various allegorical characters who guide him, favorably and unfavorably, in his quest to reach the unattainable. In the second part Jean de Meun draws on ancient stories, including Pygmalion, discusses the philosophy of love and follows the poet until he attains his goal, the rose. Two versions of the Rose were written in Middle Dutch. One fairly faithful, but shortened, version by an author only known by his first name, Heinric, and another Second Rose, inspired by the original Rose, written around 1290, by an anonymous author.

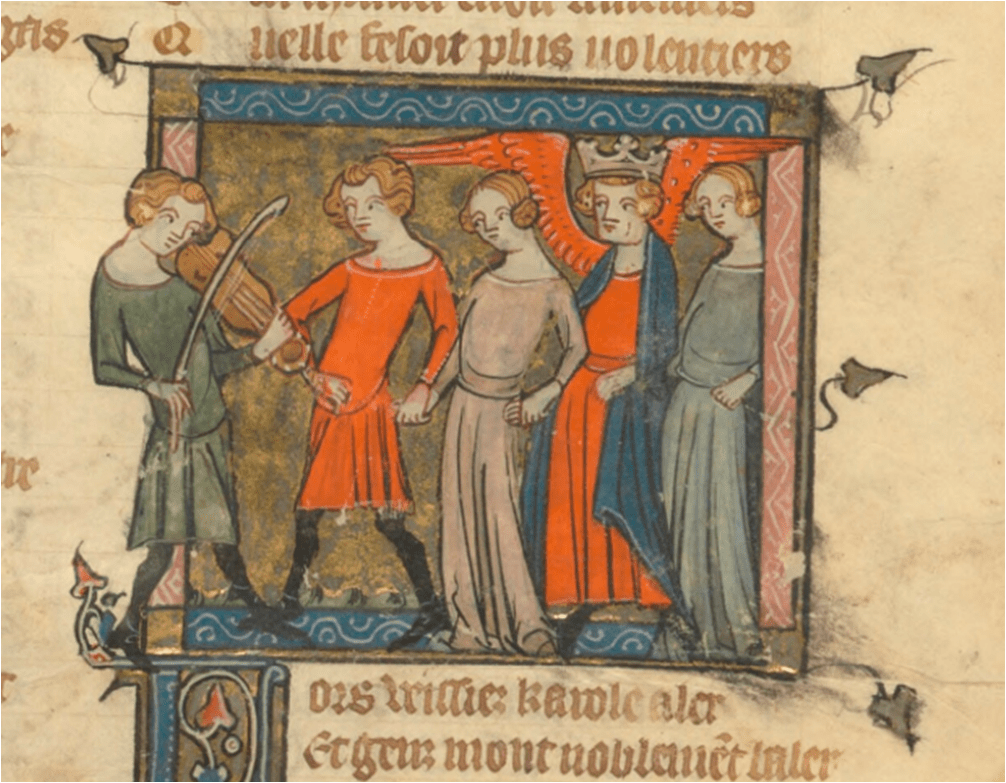

Back to the dance. Inside the enclosed garden the Dreamer sees a group of people, all allegorical figures, dancing a carole. Courtesy invites him to join in with the dancing. (“Come her, and if it lyke you/ to dauncen, daunceth with us now. “/ And I, without tarying, Went into the caroling). ** A miniature of this section appears in many extant manuscripts. Most of the illustrations were drawn by French artists. Only a handful were drawn by artists of the Low Countries. Before I proceed to the work produced by these latter artists I would like to share just a few of the early miniatures created by French artists. In the sideshow below are four of the many miniatures found in 13th & 14th century French manuscripts. Common to all the miniatures shown, is that the figures either hold hands, or are joined by means of a scarf and that the musician is placed on the outer edge of the miniature frame. In some the word carole is placed just above or just below the miniature. The carole, although often thought of as a circular dance, is not infrequently depicted as a line dance. Why? As I explained in my previous post, a carole may have been a circle dance, a line dance or a term for dance in general; thus to draw a line dance would be perfectly acceptable. Also probable is that the artist did not process the skills to draw a circle with realistic perspective and then a line dance would be the ideal solution. Sometimes, to overcome the challenge of perspective, an artist drew one or two figures with their backs turned to the reader, giving the impression of a circular shape.

- Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Arsenal 5226 – fol. 7r – 1400

- BnF fr.9345 fol.4r – c.1400

- Bibliothek der Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, A.B. 142 – France 14th.c

- BnF français 1575 – folio 5v

The Morgan Library and Museum houses an intriguing manuscript possibly made in Tournai (present day Belgium), around 1390. The miniature, named Carol of the God of Love is found halfway down the page and expands over two columns. Set outside against a gold background Amour (easily recognized by his huge wings) dances a line dance with four men and women, including a queen. On either side of the line, two young people hold hands, facing each other, but neither the two maidens, nor the two boys appear to move with any vivacity. This carole is a slow, eloquent dance, accomplished with courtly dignity.

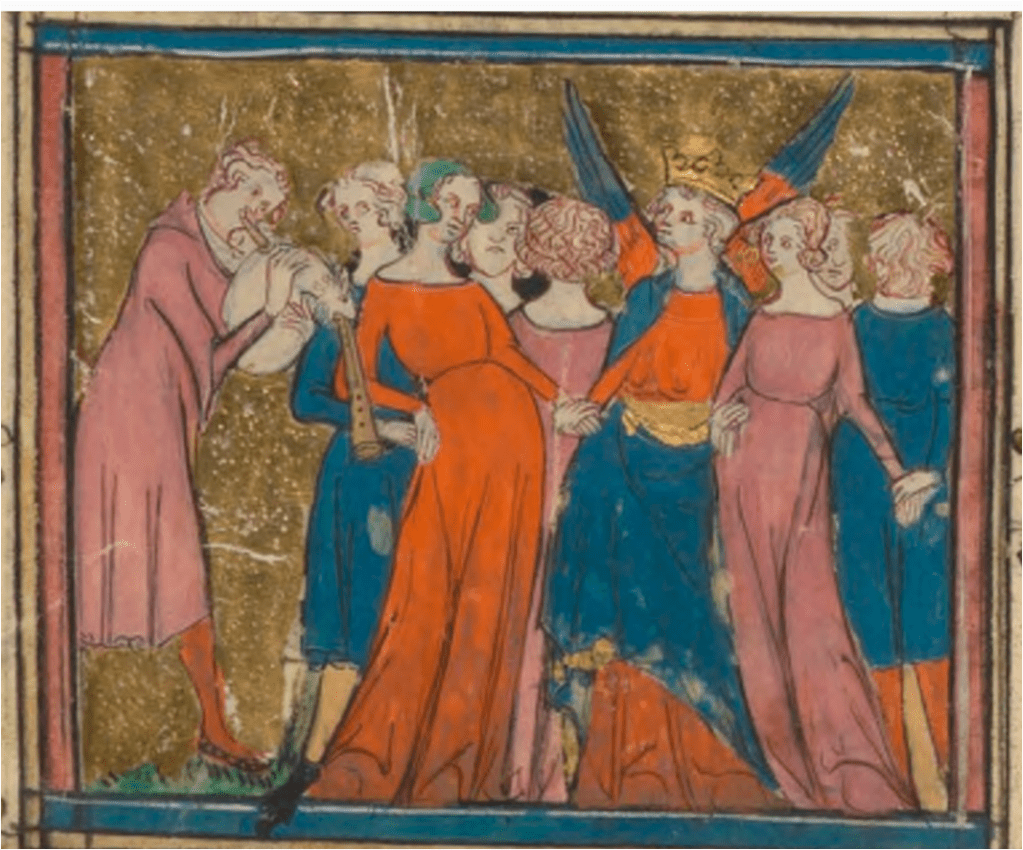

Identifying the origins of a medieval manuscript remains a difficult undertaking. BnF Ms 1567 is a 14th century manuscript, housed at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, produced in France or in Flanders. Despite the uncertainty of its origin a closer look at the miniature is well worth the effort. Amour and his entourage dance a carole (now spelt querole). This, predominately orange and blue, miniature describes a gracious line dance, where the men and women, holding hands, alternate in the sequence. This cortege of slender body types moves calmly forward in a noble fashion. Amour is the only figure to actively lift a leg. As a dance teacher, I am surprised by the posture of the men; excessively arched backs, protruding bottoms and inflated chests. The women, in contrast, all have a fairly natural posture.

In the following, red framed, miniature made in Arras around 1370, the Dreamer, having been led into the garden of Deduiz (Garden of Love) by Idleness, waits, his arms crossed, observing the dancers from a slight distance. This carole has a circular appearance; the artist placing the orange dancer just a little higher than her companions to give some impression of depth and perspective. Judging by the calmness of the dresses that fall downward without even a slight ripple, this carole, is all but an active dance. I suppose when men wear very long pointed shoes, (poulaines) you cannot expect them to perform rapid movements or jumps. Two rustic musicians, one playing the bagpipes and the other a Hirtenschalmei (or shepherd’s shawm) are propped, poised on some non-existing plateau, in the right-hand corner.

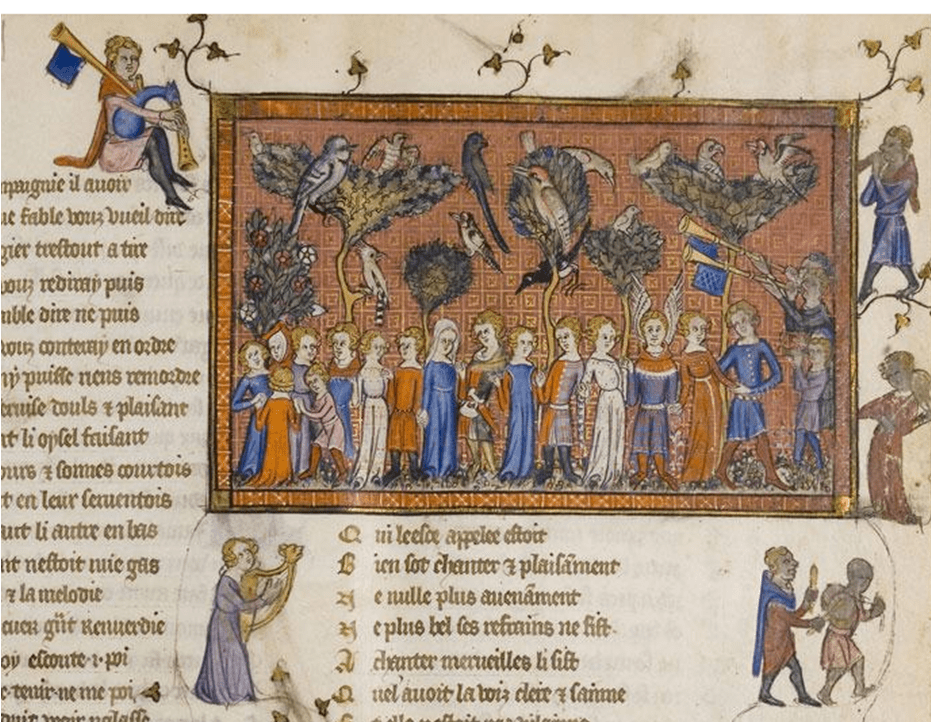

Just north of Paris, in the historical city of Chantilly, the most magnificent Book of Hours, LesTrès Riches Heures du Duc de Berry is housed at the Musée Condé. Three young men, from the Low Countries, the Limbourg Brothers are acclaimed for their extraordinary miniatures. This book of hours presents a wealth of exquisite images, but none of these involve dancers. This museum also holds a manuscript of the Roman de la Rose which does have a remarkable image of the carole episode. We see a long line of dancing men and women alternating, a handsome and very friendly Amour displaying his wings, children skipping in a small circle, six different types of trees , a great variety of continental and exotic birds and musicians blowing their shawms (trumpets) on the outer edge near the frame. Just outside of the miniatures are six more musicians, and with the exception of those playing the nakers (kettle drum) all the musicians look towards and play in the direction of the dancers.

Le Roman de la Rose was completely reworked by Gui de Mori, a poet from Picardy is the 1330’s. The illuminations, of this lavishly decorated manuscript, are attributed to the Flemish illuminator, Pierat dou Thielt, who at the time, may have worked Jehan de Grise’s atelier. No other 14th century illumination presents so many episodes of the poem simultaneously. Not dissimilar to early Italian frescoes, many scenes of the narrative, in this case regardless of chronological order, are placed on different levels within the miniature. On the lowest level, enclosed in a twelve sided garden wall, the Dreamer embraces the rose and Amour aims an arrow at the Dreamer’s eye. In the middle section there is a grove with various animals and the Dreamer gazes into the mirror of water while on the top level seventeen allegorical figures led by the god Amour, boasting his prodigious red wings, dance a long processional chain dance. These allegorical figures, for the most part represented as court ladies, hold hands, or present a hand, inviting the next figure to join in, turn to face each other or move one after the other. The chain, a partially adjoining front and back row, meanders sublimely through the Garden of Love.

At a time when it had become possible to print books, Engelbert II, Count of Nassau and Vianden (present day Netherlands) commissioned a workshop in Bruges to compose an awe-inspiring, opulent manuscript; this is now known as Harley 4425. The text, which the patron chose to be hand written was copied from an incunable (a very early printed book) and decorated by the Master of the Prayer Books around 1500. The manuscript contains four large coloured miniatures, one of which is the carole scene in the Garden of Love. The miniature is surrounded by a full panel border of flowers and insects.

The poem speaks of a carole, the text under the miniature reads carole and yet the dance shown below has none of the characteristics generally attributed to a carole. It is neither a circular nor a line dance. The dancers are not accompanying themselves in song. Rather, they are accompanied by regally clothed musicians. The figures perform a dance not seen in any of the previous images. The dancers, now dancing in pairs, are positioned side by side. One writer suggests that these dancers merely promenade in pairs *(1). Another suggests that the artist was inspired by the fashionable dance of the time, the basse danse *(2). Whichever dance this may be, The Master of the Prayer Books has certainly staged an elegant, stylish scene appropriate to the affluent taste of Count Engelbert and his noble peers.

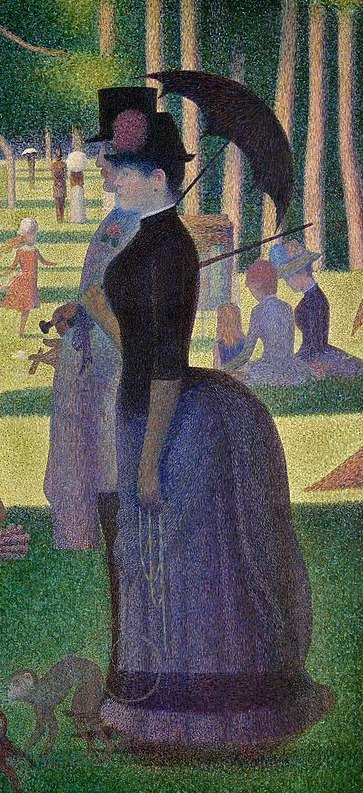

Looking at the above illustration, the 19th century French post-impressionist artist, Georges Seurat crossed my mind. I could not help noticing that the stance, dress and expression of the two ladies shown below, even though they were painted four hundred years apart, are comparable. No doubt the similarities are purely coincidental. Just a random thought I wanted to share with you.

** Lincoln Kirstein – The Book of the Dance 1935 (page 93)

* (1) – John Fleming – Roman de la Rose: A Study in Allegory and Iconography 1969 ( page 84)

* (2) – Robert Mullally – The Carole: A Study of a Medieval Dance 2011