Secular manuscripts grew increasingly popular during the 14th century. Especially celebrated were the legends of Alexander the Great. The profusely illustrated, Romance of Alexander (MS Bodley 264) , written in the French vernacular and illustrated by the Flemish artist Jehan de Grise and his workshop between 1338 and 1344 is just one of the many manuscripts relating the breathtaking adventures of the Macedonian king. It is a large manuscript containing 274 folios. The pages are 415mm by 295mm in size. This lavish and undoubtedly heavy manuscript was intended to be read out aloud. The narrator sat, possibly near a warm fireplace, surrounded by captivated listeners. It is easy to imagine an audience of noble ladies and gentlemen together with a scattering of youngsters, listening to the adventures of Alexander whilst gazing over the shoulder of the story-teller to enjoy the many beautifully illuminated miniatures and countless fanciful marginalia.

Dance features predominantly in MS Bodley 264. In fact, no other 14th century manuscript produced in the Low Countries, or in any other country for that matter, contains such an amazing range of dance images. This blog will focus on dances performed by nobles & courtiers and on an entertainment form called mumming.

Before discussing the individual dances, I would like to point out that it is not the task, nor the intention of an artist to produce authentic dance illustrations. Artists are free in their interpretation, their expression and in their creative process. An artwork may give an indication of the period, the style and how a dance was performed, but these images will always be subject to artistic license. Pondering over the deportment, the dress, the formations and the type of instrument accompanying the dances allows us to speculate, and no more than speculate, as to how these dances were actually performed.

In this bas-de-page illumination a seated hybrid musician, playing a lute or gittern, accompanies four refined couples. The men are smartly attired carrying handsomely made accessories, such as daggers and purses, becoming to their noble status. The women’s gowns are meticulous; a row of white buttons embellishes the front of reddish-brown gown and these buttons are reciprocated on the gentleman’s sleeve. The couples to the right are conversing and you may have noticed that the man standing nearest to the musician has a hawk perched on his wrist. The two couples on the left are actually dancing; their movements closely resemble each other. Both men step forward simultaneously, obviously following the tempo set by the musical hybrid, and they and their splendid ladies lift their arms in a very similar way. Considering that their movements are synchronous the couples, in all probability, perform a well known, fashionable dance.

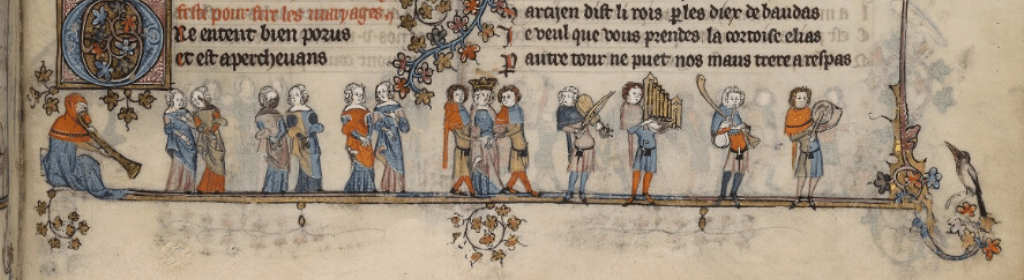

The following two successive folios show courtly figures promenading in a procession and dancing in various formations all to the accompaniment of an assortment of musicians. The attendants strolling behind the queen are as sophisticated as one would expect from ladies-in-waiting. Striking is that all the ladies are of the same height and build. This is characteristic of many of the dance images; perhaps the artist enjoyed the sight of a harmonious line. The uniformly shaped women wear originally adorned gowns trimmed with various decorations. They are serene, move in style and judging by the manner with which the Queen is escorted, their tempo is likely to be quite leisurely.

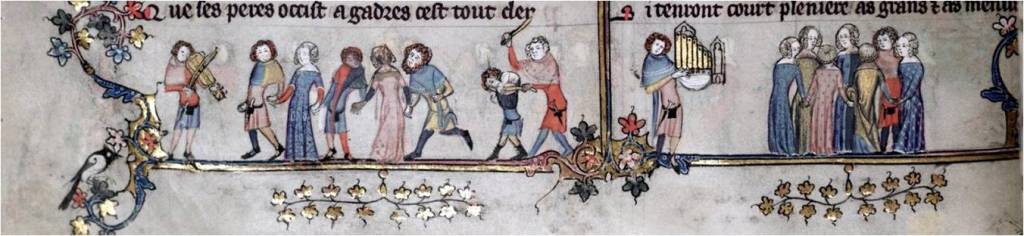

Between the fiddler and the nakers (kettle-drums), five men and women are enjoying a line dance. Similar to the other images, mentioned above, their height and body shapes are quite uniform. In the right column is an image of a circular dance performed by six maids and a youth. There are only two images of a circular dance in the manuscript; this bas-de-page example and a miniature on folio 181v. A circular dance is often referred to as a carole. There is however much uncertainty as to how a carole was actually danced. Experts query whether the carole was a line dance, a circular dance or even a combination of both. The term carole may refer to a specific dance, but it is equally possible that the term refers to dancing in general. What we do know is that there was no single way of dancing a carole. It is believed that the formation of the carole depended on the place where it was danced. In narrow streets the carole could be a long line dance with participants following the leader. Where space was plentiful, a plain or court hall, the carole would likely take on a circular formation. The carole was danced by men and women, young and old from all social classes, therefore suggesting that the steps and movements were free from complexities. From contemporary sources we know that the participants sang as they danced. Perhaps you are reminded of the Christmas carol; be assured the word carol is a descendant from carole, the medieval dance form.

The bottom border of folio 175r depicts a row of seven male courtiers and a row of six fine ladies accompanied by a drum and bells. Immediately one notices the uniform height of the ladies and their similar body shape. All the ladies move identically except for the lady in clad in light blue that turns her head towards the lady behind her. The arrangement of the line gives the impression that the ladies are moving forward, but oddly enough their shoulders and hips face to the front; a position well-known from ancient Egyptian and Greek art. The slim courtiers with their well-tapered waists bearing purses and knives, all face the front as if waiting for the ladies to approach. Why are there six men and only five women? I can only imagine a dancing game reminiscent of ‘musical chairs’, where the man who fails to score a partner must relinquish his place in the dance.

But of more importance than my speculation is that this image and the previous images enhance the narrative. Marginalia, as we have seen, is frequently quite independent of the written text, but in this case, they interact with the narrative; the tale of Alexander presiding over various weddings followed by days of celebrations and festivities. Music, singing and dancing, play an essential part role in the revelry. The word chanter appears in the text, but more significantly caroler appears three times within a few folios. These bas-de-page images accentuate the festive mood of Alexander’s adventures.

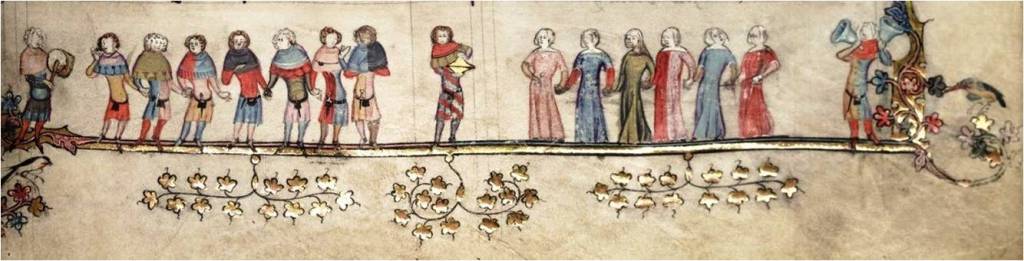

One of the most popular forms of entertainment, in the villages, towns and at court, was mumming. Customarily mummers were costumed village folk who at Christmas time, disguised themselves with masks, travelled from house to house, gave performances, sang a song, told jokes and after enjoying some refreshments continued on their way. But the mummers, in folio 181v, are not peasants. If we disregard the masks for a moment we notice that they are remarkably akin to the couriers in the above illustration. In both cases the clothing is similar, the men have slim physiques, tapered waists, and lunge slightly to one side and some carry purses or bear daggers. These masked mummers wear a cape, just as the courtiers in the above image, only this time the cape is decorated with a heraldic coat of arms. Likewise the ladies on the right side are a near copy of the ladies in folio 175v. The courtiers and ladies, hands joined, perform a line dance possibly to the music notated in the musical stave immediately placed above the mummers.

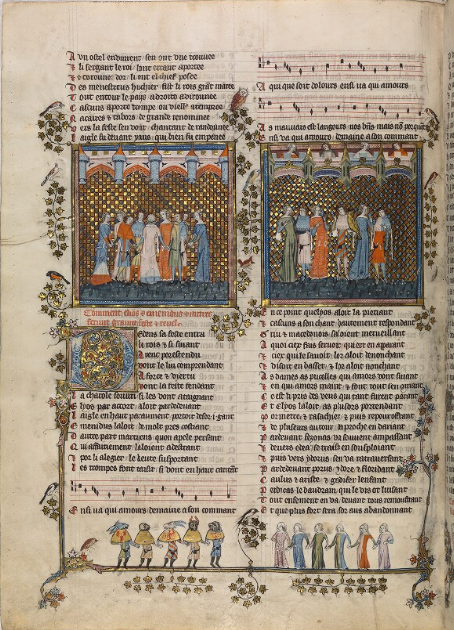

Folio 181v is a unique page; a feast of dance and music. This is the only page I have found, within 14th century manuscripts where dance, music, text and art interweave. Each art form compliments the other, amplifying the festivity of the narrative. The miniature, a carole, illustrates the text which starts two lines below the image describing the company dancing at the conclusion of a debate. This miniature, the only dance miniature in MS Bodley 264, presents the carole as a circular dance where men and women alternate, holding hands, in an elegant choreography. Augmenting the miniature is three staves of musical notation with corresponding lyrics. This was the only music notation in the entire manuscript and one of the few musical inserts found in secular manuscripts of the Lowlands in the 14th century.

Let us revisit the image of the narrator reading this page out aloud to his elite audience. I could imagine, on hearing the text, perusing the illustrations, seeing the music, envisaging the dance that the medieval listener could fantasize himself in Alexander’s court. A musical courtier might hum the tune. An instrumentalist might join in. Yet others may feel inclined to dance a carole which after all was a commonplace dance. In the late medieval world secular books were not meant to be read in silence, but to be recited aloud. This folio with its exquisite harmony of music, text, dance and art touches on a variety of senses.

– miniature showing dancers performing a carole & complete folio

For an excellent study on MS Bodley 264: Illuminating the Roman D’Alexandre: Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 264 by Mark Cruse.