In the high Middle-Ages the demand for manuscripts no longer primarily focused on religious or devotional books. Where initially manuscripts were the domain of monasteries with monks working laboriously in a scriptorium, by the 14th century urban workshops were producing manuscripts and selling these commercially. Books became accessible to a much wider audience. Increasing urbanization, the rise of universities, increased literacy and the development of a wealthy aristocratic culture resulted in a demand for secular manuscripts. The devotional Book of Hours remained immensely popular, but, the elite also wanted to read entertaining and educational books and they wanted to read them in their own vernacular. The new literary forms included the bestiary, scientific texts, history books as well as entertaining narrative romances and historical adventures. The most favoured subjects were the Arthurian Legends, Adventures of Alexander the Great and Le Roman de la Rose.

The legend of King Arthur was possibly based on a 6th century Welsh historical figure about whom the 12th century author, Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote in his partially fictional historical work The History of Britain. The legend of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table is a tale of chivalry, courtly love and military achievements; all elements that appealed to the aristocratic audience. In the 12th century the French poet and trouvère Chrétien de Troyes popularized and expanded the legend, adding the Knight Lancelot, as a main character, in his poem Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart. The Arthurian Legends, with whom the noble audience liked to identify themselves, was immensely in vogue and subsequently appeared in France, Britain and in the Low Countries.

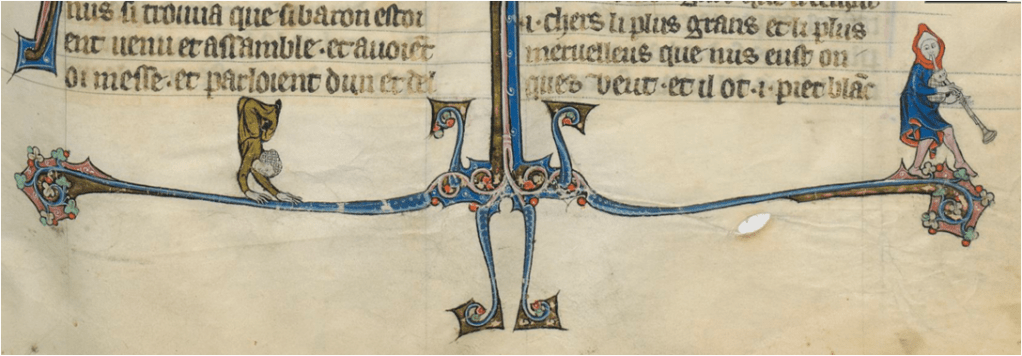

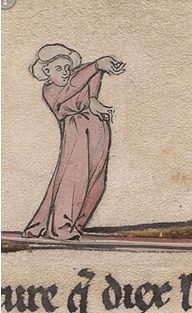

An early Arthurian Romance (BnF fr.95) was produced in Saint-Omer in the late 13th century. Interspersed within the text are folios decorated with exquisite miniatures. On the same pages meticulously drawn borders and fascinating marginalia are added. These, in contrast to the miniatures, have no apparent connection to the text, although at times the artist may comment or even satirize elements of court life. The tiny, delicately drawn figures include various dance scenes ranging from an elegant dancing lady*, to a performer on stilts, tumblers performing acrobatic feats, dancing bears and an image of a mummer impersonating a stag.

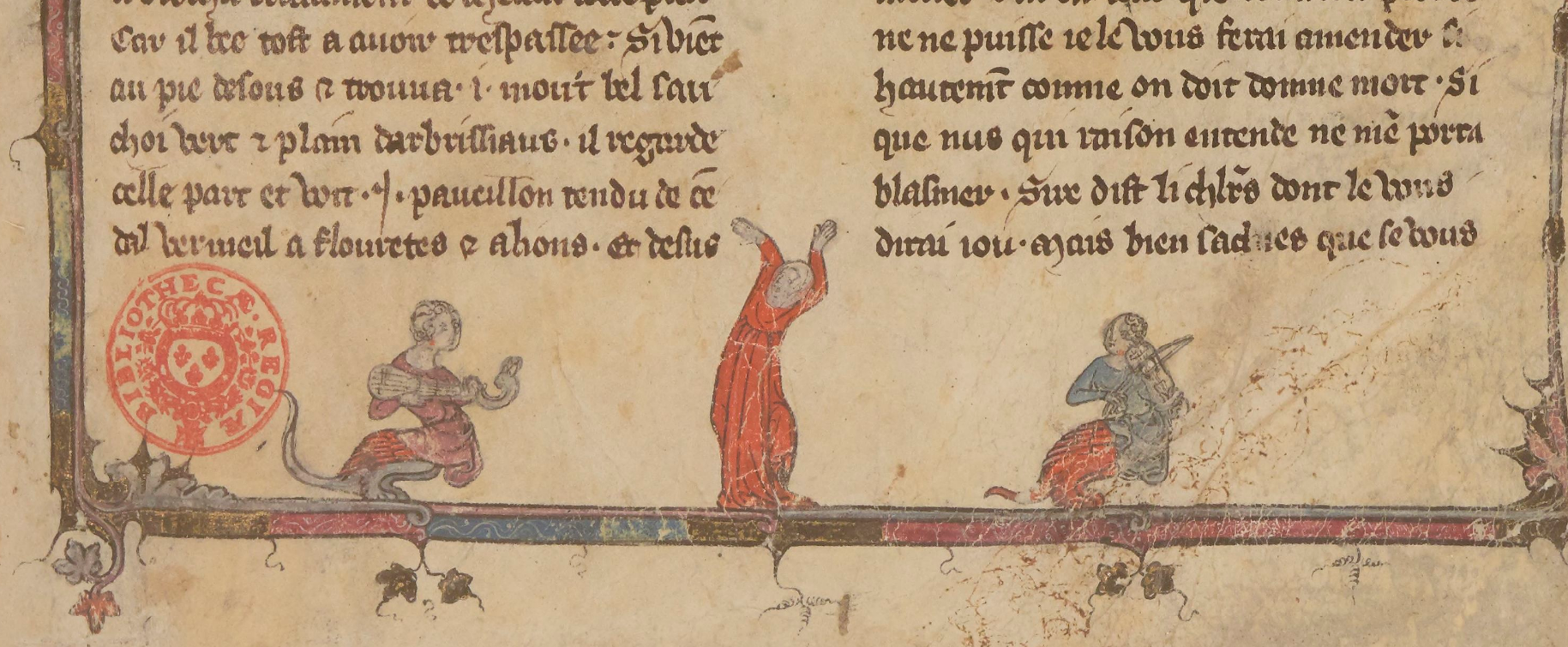

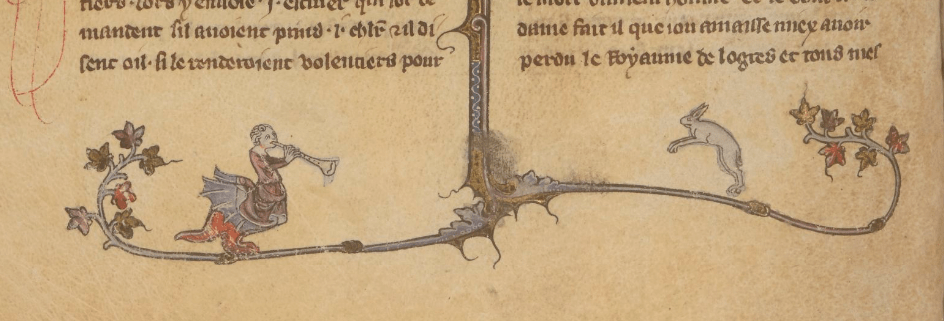

The Bibliothèque nationale de France houses many versions of the Arthurian Legends including Lancelot du Lac produced in Tournai around 1330-1340. The only dancer in this manuscript finds herself placed between two bizarre musicians. Her arms are held high in the air in a most extraordinary, perhaps even anatomically improbable, position. The alluring dancer rolls her hips as if mesmerized, swaying to the sounds of the hybrid companions. A little further in the manuscript there is a trumpet playing hybrid enticing an anxious hare to prance around. There are, of course, elements of magic and mystery in life of Lancelot, but one wonders how a prancing hare and hybrid musician fit in?

The production of Arthurian Legends thrived. The manuscript BL Royal 14E III is decorated with 116 miniatures and BL Additional 10293 holds 436 miniatures. Both were produced in the first quarter of the 14th century in the Tournai or Saint-Omer region. The opening pages of each manuscript are similar; Gothic architecture, knights on horseback, musicians, animals and dancers standing on the shoulders of a musician. The two dancing ladies, shown below, find themselves halfway down the page in the left margin. As customary, the musician and dancer, people of poor repute are placed on the outer border. The musician, in the right image, has a sturdy line-extension to stand on but the other less fortunate bagpiper merely hovers in the air. The two musicians are practically copies of each other; only the bagpipe itself and the decorative ‘face’ are different. Likewise the dancers are almost identical, dressed in their blue and red gown topped with a half-length light coloured scarf. And their dance style is typical of the period; hips gently swayed to one side, one hand on the hip and the other arm lifted above the head. That these figures are so comparable raises the question if they were drawn by the same artist. Possible, but improbable. More plausible is that the artists worked in the same or neighboring workshops or, considering that commercial artists were active that the use of stencils or templates had become commonplace.

Tristan, besides being the lover of Iseult (Isolde) was also one of the Knights of the Round Table and participated in the Quest for the Holy Grail. His tale, Le Roman de Tristan, is told in a 13th century manuscript produced in Arras. Amid the pages of precisely drawn marginalia is a most unusual dance image. A female musician, posed in the familiar dancer’s position with subtly protruding hip and one leg extended nonchalantly to the back, is playing for the male dancer performing on the other side of the centre line. Manuscript-wise male dancers are in the minority and mostly cast as hybrids, grotesques, mummers or jongleurs. This male dancer, complete with short beard, is a true to life figure. But I am troubled by his bearing. No dancer would feel sturdy with one leg raised to hip height and the other foot clamped over a connecting ridge. Either this fellow has a superb muscle tone that enables him to sustain this apparently easy-going pose or the artist had no idea how demanding a position he had drawn.

The Arthurian Romances often referred to as Yale 229 is a medieval masterpiece housed at Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscript Library, Yale University. The miniatures, including one of Lancelot dancing with a group of ladies, are superb. The miniatures relate closely to the narrative and here too, as previously mentioned, the marginalia are decorative but do not shun away from a little mocking satire from time to time. One of my favourites is a drawing of a hare gone hunting. He carries his catch, a man, on his back. (folio 94v)

Musicians, playing an array of different instruments, are frequent inhabitants of the margins. Dancers are less frequent but no less interesting. Below are three dancers highlighted from the marginalia. Their attire, hairstyle, carriage and dance movements closely resemble each other. Very similar ladies appear in a framed miniature dancing, perhaps a carole, hand in hand with the knight Lancelot. The faces and expression of the women in both the marginalia and the miniatures are alike, not to mention the gentle sway of the bulging hip. Have the dancers in the marginalia, that area once reserved for folk with a low social status, gained more respectability or is this similarity purely coincidental?

f. 75r

f.187r

f. 137v

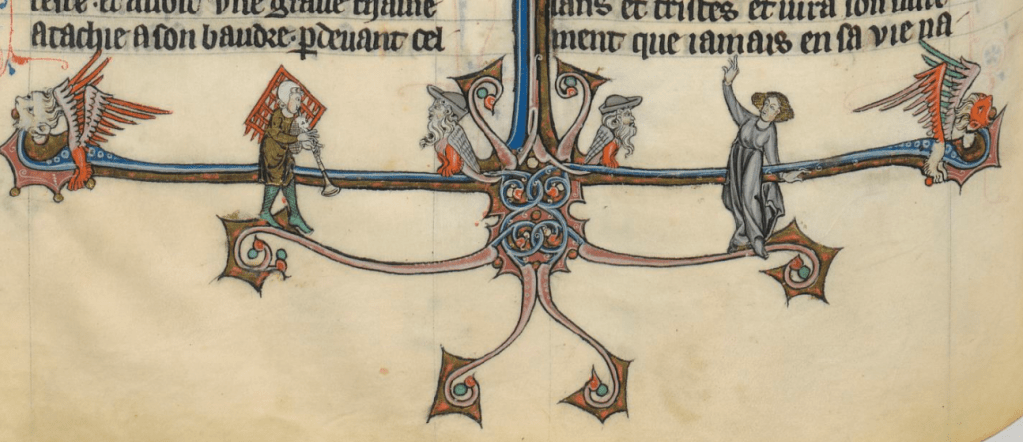

It has been suggested that Yale 229 and BnF 95 may be pendants. Together they could possibly form the entire Lancelot Cycle; Yale 229 constitutes three sections and BnF 95 another two. The middle section has been lost. I gladly leave this research to the experts, but I will draw your attention to an irresistible comparison. Browsing through the manuscripts, the sameness in the manner of drawing, the use of colour and the choice of subject matter throughout, caught my attention but none more unanticipated than the two illustrations below. The setting is comparable; an ornamental curvilinear centre complete with grotesques, from which two extensions emerge each travelling to opposite sides. The dancers too are notably similar. Not only do they execute the same movements, their facial features, deportment and carriage of the head closely resemble each other. The same applies to the bagpipers. Even though the fellow wearing the red hood is striding forwards and the other musician is playing on the spot they share a common appearance. Furthermore they both carry an open square grid-like construction on their backs. I have met this type of construction only once before, then in triangular form, and presume it to be some type of musical accessory.

One final observation. Comparing the two dancers, shown below, it is apparent that their finely detailed facial features and calm expression, their hairstyle, their courtly elegance, the predominately flexed hand, not to mention the slightly angular fingers, are common to both. Yet these ladies, despite the strong similarity, originate in two different Arthurian Romances manuscripts. The questions have already been asked. Are we looking at the work of the same artist, the same atelier or at a flourishing market for stencils? The answer may remain a mystery but, in the meantime, it is a fascinating puzzle to explore.

BnF fr.95 f.324v

Yale 229 f.187r

* Dancing lady – BnF fr.95 fol.324