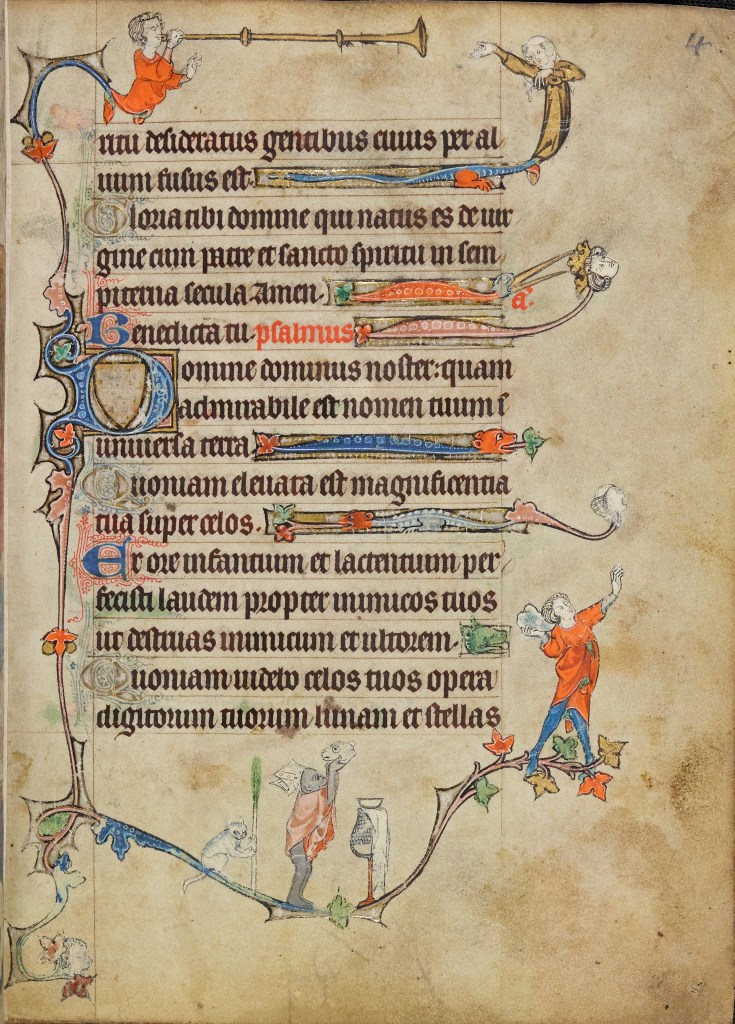

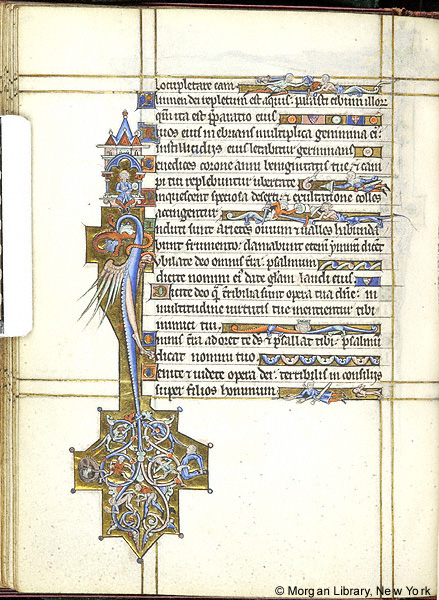

Illuminated manuscripts were embellished with miniatures, decorated initials, marginalia and an infinite variety of borders. In 14th and early 15th century manuscripts, images of dance and music are mostly allocated to the outer margins, often in the form of a line-filler or as a vine-like extension originating from an initial. The folio below gives an impression of both forms of embellishment. Starting from the initial ‘D’ an extension (or extender) ascends to the top of the folio before becoming a half-figure musician playing a trumpet. Moving down from the initial the extension descends to the bottom of the folio creating a platform for a man’s head. The same extension branches off curving along the bottom of the leaf, bypassing a cat, a monkey and a bowl sitting on a standard, to stop just outside of the written text. The foliate extension ends with a man standing in a typical ballet position. His back leg is elegantly extended and his torso has theatrical poise. The artist has drawn a position which, with a little imagination, looks very similar to a ballet pose called an arabesque. Nonsense of course; this manuscript was created hundreds of years before ballet evolved. My only explanation is that the artist was familiar with deportment skills and social graces as practiced by noble men and women.

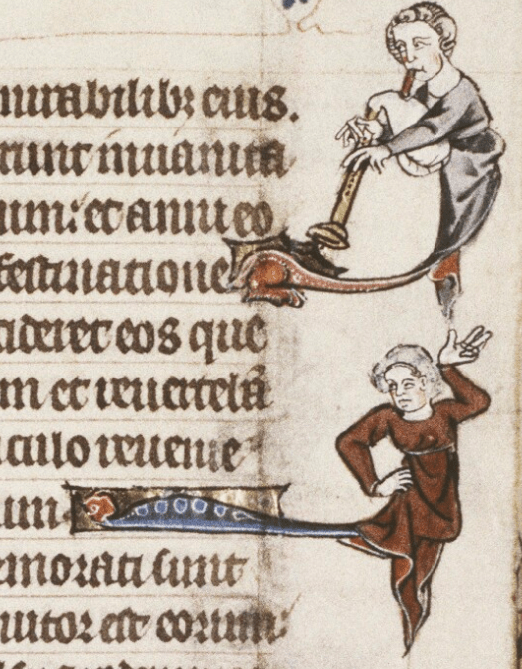

A line-filler is a decorative devise filling the space remaining after the scribe had finished writing his text. The length varied according to the space that needed to be filled. The images ranged from geometrical patterns, birds, dragons, animals to musicians and dancers. Often the line filler was extended even further by adding an extra feature such as an ornamental head, half-figure or hybrid. In the example featured above the artist has chosen freestanding heads, a bird with an open beak and a half-figure dancer blossoming from the neck of a dragon-like figure.

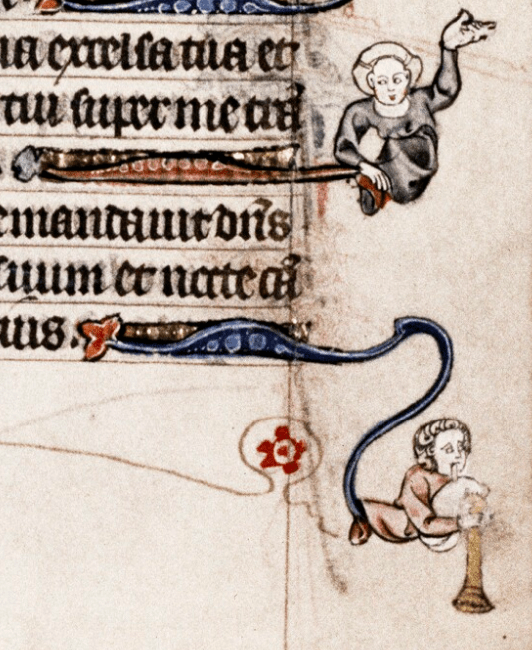

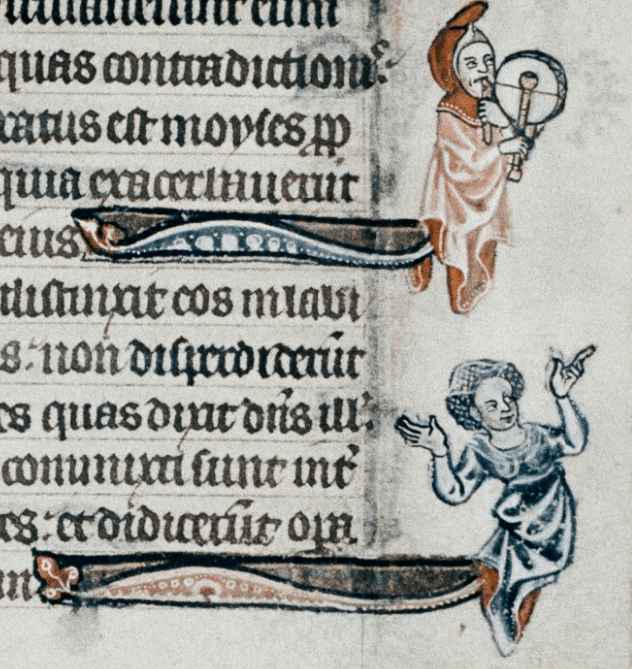

Drawn-out dragons and elongated birds were popular line-fillers. In an early 14th century manuscript, Psalter Douce 5 & 6, nearly all the added figures (terminals) flow out of dragons or evolve from ambiguous animal shapes. The half-figure dancers and musicians hover in the margin, having been propped onto the outer end of some headless imaginative creature. Their robes either hang freely or a carefully entwined around the line-filling; they remind me of hand-puppets resting on a stick.

Bodleian Library MS. Douce 5 f.119r- Psalter – Flanders (Ghent) 1320-30

Bodleian Library MS. Douce 6 f.63r – Psalter – Flanders (Ghent) 1320-30

Of all the manuscripts I have browsed through I found that the Psalter-Hours of Ghuiluys de Boisleux (MS.M.730) contains more dance or dance related images than any other manuscript of its time. Made in Arras around 1250 for the noble woman Ghuiluys de Boisleux this manuscript features dancers in some of the miniatures and in many initials, line-fillers and extensions. The Psalter-Hours is a devotional manuscript containing a wonderful selection of miniatures all related to the biblical narrative. Be that as it may, outside of these miniatures we are treated to jongleurs performing the most outlandish movements, nude and dressed dancers pouncing around initials, dancers and musicians intertwined with dragons and figures running and rollicking over the line-fillers.

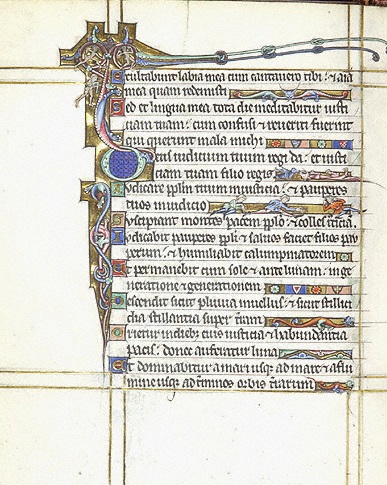

To start with line-fillers. I apologize for the poor quality of the illustration below, but, despite that, it does give a good indication of the line-fillers used throughout the entire manuscript. The Morgan Library & Museum (link above) has placed the entire manuscript online and gives a comprehensive page by page description of all the images. The line-fillers on this page range from fantasy animals, heraldic escutcheons from both the family of Boisleux and her husband Jean de Neuville-Vitasse, bird pecking a fox, geometric patterns and, on the fourth line-filler, dancers.

The line-fillers are rectangular in shape and generally have a gilded background. They all end in a fairly straight line, the ruler lines forming the border. The margins are left vacant with the exception that thin threadlike lines are recurrently added to denote, for example, an animal’s antenna or beastly stuck-out tongue. Dancers, acrobats, jongleurs and musicians are a recurring motif. Sometimes three dancers all face the same way, sometimes two, some figures turn towards each other, occasionally a woman dancer joins in or a musician is added to the row; any combination is possible. Most of the figures are clothed, but there is a fair share of undressed dancers. To enable the figures to fit into the long and narrow space their pelvis is located near to the lower line of the rectangular bar. Some dancers perform the splits, some are practically lying down or yet others sink into a very low knee bend. Their heads generally pop up above the gilded rectangle whilst their legs protrude downwards barely avoiding the written text immediately below them. All the dancers are lively, dashing playfully to and fro.

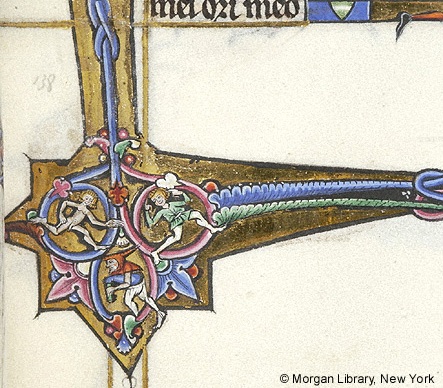

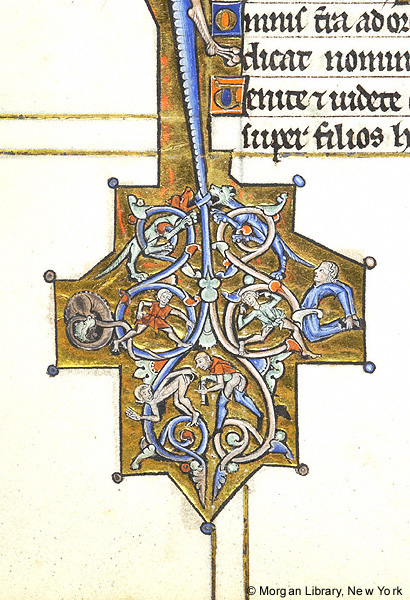

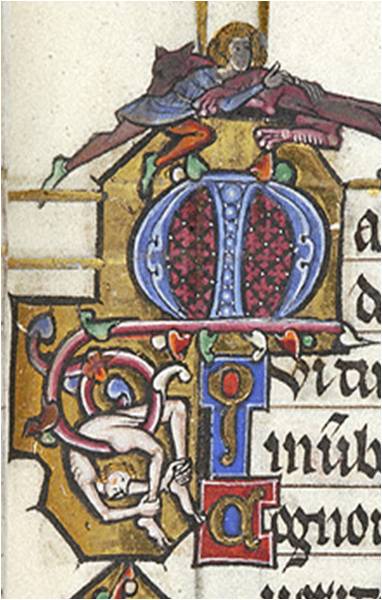

Extensions develop from an initial. Dance-wise the Psalter-Hours Ghuiluys de Boisleux has two variations; extensions reminiscent of a sophisticated clover-leaf with dancers and musicians interlacing at an intersection and secondly a single performer executing a formidable acrobatic movement suspended by a dragon’s tail, a thick vine, a rod or a variety of similar possibilities.

Right – detail (click to enlarge)

The above illustration represents the initial I. A musician playing a pipe and tabor is seated on a platform under a Romanesque arch. Moving down along the dragon’s tail the initial develops into a nine-point geometric structure enclosing curvilinear shapes. Interlaced amid the various curls are dogs, a strange creature, two dancers, an acrobatic dancer and a half-nude musician who is more than interested in the figure perched in front of him.

The two dancers, each enclosed within a circular shape, are jovial figures. The chap in the red tunic moves forward hastily. His legs are widespread giving the impression that he is taking enormous strides. Likewise, the other figure also rushes forward with no less haste. A very difficult feat considering he leans backwards, looks backwards and has both arms bent pointed towards his head.

These two dancers, and indeed all the dancers, pictured in the extensions are remarkably similar to the dancers that occupy the line-fillers. These cheeky figures embellish numerous initials. Whether they are dressed or nude, whether they are running, turning or gallivanting feel assured there is a dragon or some fantastic animal looming in the vicinity and a bagpiper close-by.

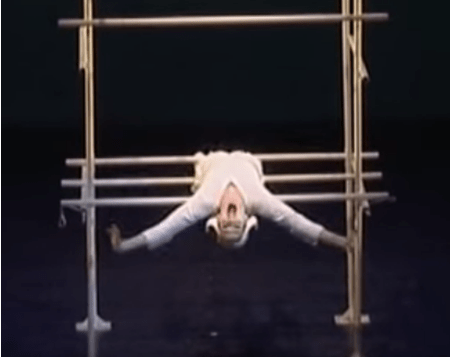

The second and most spectacular extensions are the acrobats, dancers and tumblers who perform startling feats. Keep in mind that this Psalter-Hours is a devotional book belonging to a most distinguished lady and used for devout contemplation and reflection. And yet, these illuminations are so eccentric that you could forget the pious nature of the manuscript. Very little is known about Ghuiluys de Boisleux but judging by this manuscript she must have had a great sense of humour; contortionists contrive themselves into inconceivable positions, nude performers hang on scaffolding or in rings and well-dressed ladies form caryatids supporting the extensions.

And then there are a series of tumblers hanging upside-down in the most hazardous locations. All looks innocent enough, but whether they are holding onto a rod or intertwined within a dragon’s tail, these tumblers are basically trapped. The tumbler hanging onto the rod has no space to turn and even if he could escape there is a red dragon and a devil devouring dragon awaiting him. The fate of the other tumbler is no less dubious. A dragon has weighed him down with his gigantic paw entangling him in the most wretched fashion. Yet the tumblers show no sign of distress. They simply hang there. Both have spread their legs wide to the side; one has both legs positioned behind his arms and the other has fixed himself in a most curious position. He has one leg in front and the other leg placed behind his arms. The bloomers emphasized by their distinct whiteness cannot fail to gain attention. Their other clothing naturally droops down, but their hair remains correctly in place as if they were standing upright.

fol. 233v & fol. 219v

Do these images represent dance? A fair question. All these runners, tumblers, jongleurs and acrobats may not fall into our general idea of dance or dancers. Yet they are all dancers. Dance, in the Middle-Ages as today, embraced many forms of movement. Contemporary choreography confirms just how extensive the dance language is today. Many present day choreographers have embraced non-traditional movements and embody these innovations into their work. Dancers today are no less challenged than their Medieval colleagues.