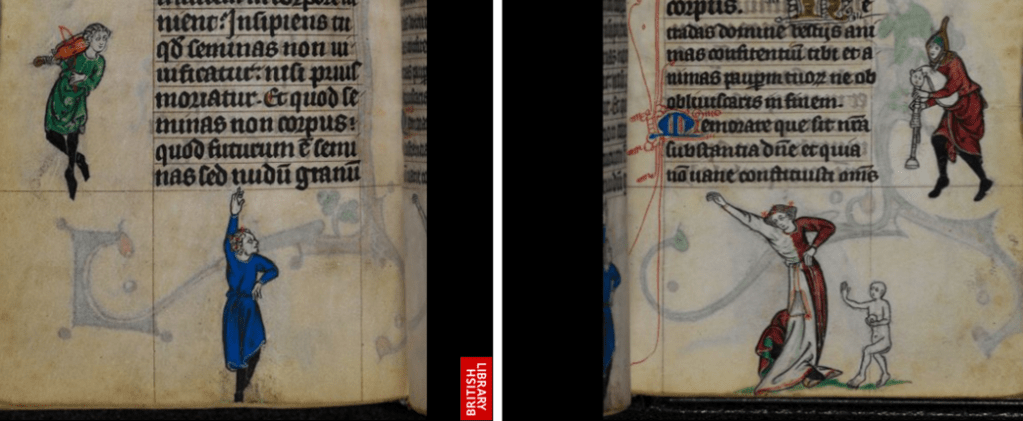

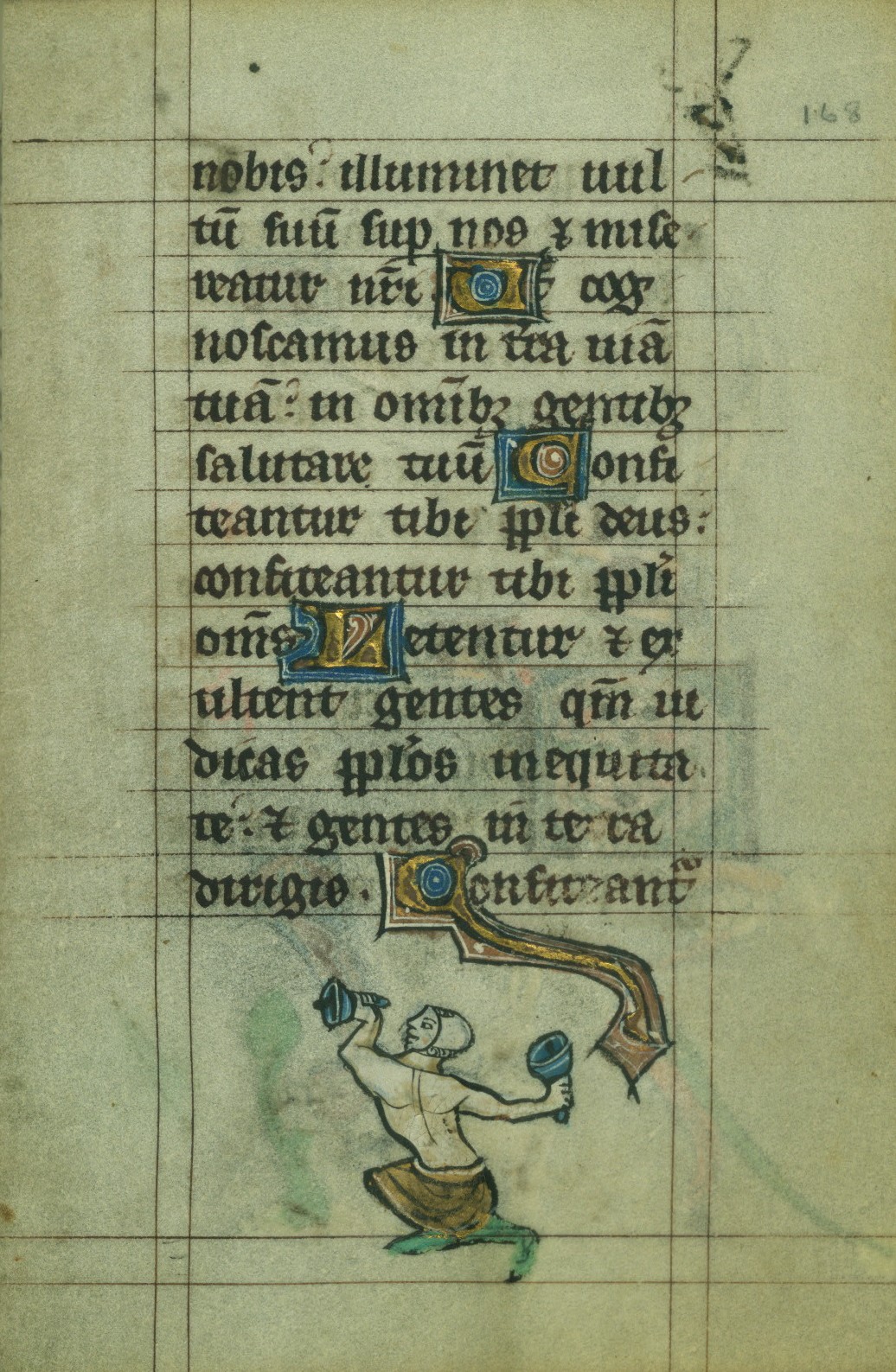

Bas-de-page, you may recollect from my previous blog, is that area of the page under the written text; literally the bottom of the page. You may also have noticed the horizontal and vertical lines drawn on the pages of illuminated manuscripts; this process is called ruling. The scribe marked out a framework of lines, as shown in the images below, within which he wrote the text. In the remaining space artists drew the most diverse drawings. At times the patron stipulated which images were to be drawn but just as often the illuminator had a free hand. The bas-de-page area was customarily illuminated with wondrous images ranging from relative realistic figures to the most astonishingly weird creatures. Illustrated below are three images from Ms. W.88 ranging from fairly credible to totally absurd. This book of hours, Walters Art Museum’s manuscript (W.88) is packed full of amusing drolleries and many of these are musicians, dancers or some bizarre dancing hybrids with an equally curious instrumentalist.

Walters Art Museum Ms. W88 – Book of Hours – French Flanders – early 14th c. musician with bells (f. 168r), musician & dancer (f.41r), two hybrids (f.50r)

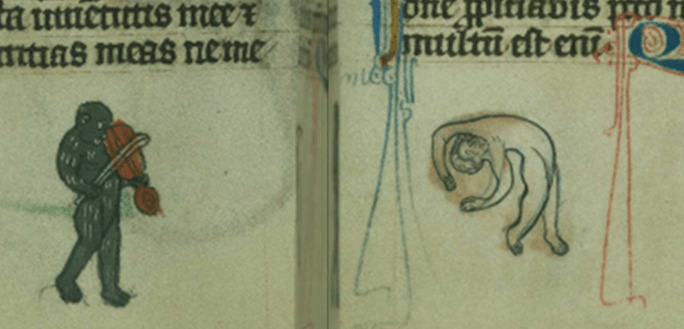

Walters Art Museum has another treasure; an early 14th century a book of hours made, possibly for a Beguine, in the north of present day Belgium (Liège). Literally a pocket edition, this miniature manuscript (6.9 cm X 9.1 cm), abounds in gilded miniatures, initials, ornamented borders and an extensive array of drolleries. The manuscript Walters Ms. W.37 contains two intriguing dance scenes. I wrote about one in the blog Dancer and her musician. Below the other scene; a double folio from a specific section of the book of hours with prayers to be recited over the body of a dead person called The Office of the Dead. A drawing of a musical monkey and nude dancer, in this especially pious and reverent section of the manuscript, might appear unforeseen. The monkey, playing a vielle, is very interested in the acrobatic dancer on the opposite page. She is an exceptionally agile contortionist suspended in an awkward back-bend. Such a position is impossible to sustain; it can only be achieved whilst passing from one movement to the next. It would appear that the artist struggled to achieve the correct position. Close scrutiny shows preparatory underlines and erasing in the positioning of the arms and right leg.

But is this odd couple actually so unforeseen? In the Middle-Ages string players had a bad reputation, were associated with tavern culture and they were generally considered corrupt. Even worse this string player is a monkey and monkeys, those imitators of human behaviour, embodied the most unrefined aspects of human nature. Music, it was said, led to dancing; a vulgar physical display where the body was corrupted into grotesque shapes defiling the human form as created by God. In the eyes of the devout woman, who originally owned the book, this unclad disfigured dancer is unquestionably grotesque. To her, this scene was a confirmation of the lust, depravation and all that she must keep at bay. This unlikely scene is a reminder and a warning and as such, for a person in the Middle-Ages, totally compatible in the Office of the Dead.

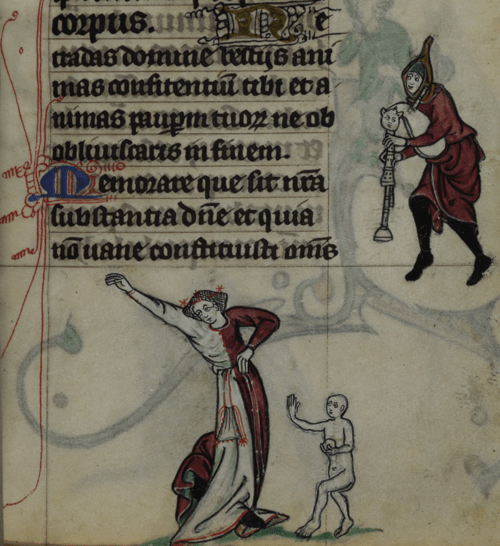

The Maastricht Hours, another extraordinary early 14th century liturgical manuscript, is so small that it fits comfortably into the palms of the hands. Page after page of this tiny book of hours is lavishly decorated with secular, devotional or fantastical images. Amid the many beautiful high-winged angels, cheeky and misbehaving monkeys, indescribable grotesques, strange musicians and dancing hybrids are three actual female dancers and a dancing nun.

The dancing lady, shown above, is depicted in a soft curvature leaning firmly to the right towards her partner on the opposite page. Her voluminous skirt swivels along the floor which could suggest that the dancer is turning energetically. The bagpiper’s bearing and enthusiastic playing is a further indication of the vivacity. Her blue clad partner stands upright and is evidently resolute. This dancer, despite balancing on one leg, is undeniably aware of the alluring lady. The dancers are obviously attracted to each other. The musician, in the margin above him, virtually stands on tip-toe as he balances on a guide line. He peers inquisitively over his shoulder at the dancer below him. All in all a pleasant scene if it were not for the small nude figure carrying a round object standing precariously close to the female dancer. His right hand is raised, his wrist pulled backed as if commanding the dancing to cease. When you realize that these pages are part of the Office of the Dead and that dance was scorned by the church, this scene swiftly loses its gaiety to become a genuine condemnation of the lewdness and the immorality of dancing.

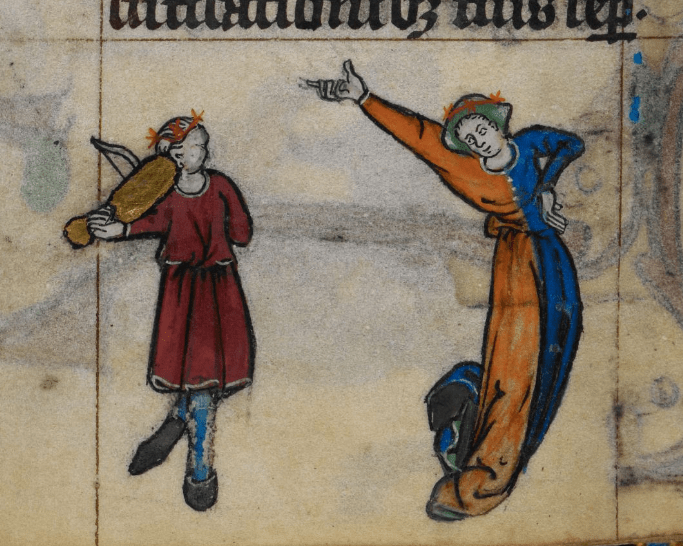

The other two dancers, shown below, are very similar in appearance. The dancing ladies are clad in orange and blue apparel. They even have the same white buttons on the front of their bodice. The only difference is their headdress. The dancer standing on the shoulder of the musician wears a white cap, the other dancer a greenish cap decorated with a garland of distinct thorny marks. Even though the dancer on the right is perched on her partner’s shoulders there is a marked similarity between her and the other dancers. Just as the others she leans sideways though her inclination is less oblique. Likewise one arm is lifted and her left hand rests on her hip. She however is not inclined to her musician but is more concerned by the monkey standing close-by. Interesting to know is that The Maastricht Hours abounds in monkeys doing anything and everything from carefully carrying a human baby to spinning yarn to poking a horn in another monkey’s backside. You will remember monkeys are not a respectable sign. This image can be viewed as a culmination of the shameful. A satirical look at music and dance intensified moreover by the monkey playing a tabor.

As point of interest; the dancer on the left is also very similar, in movement and in attire, to the dancer in the above illustration. Both dancers incline sideways to the right, both stretch towards and relate with the person beside them and both their gowns swirl copiously around their legs. These two dancers were either drawn by the same artist or, equally possible, the artists working in the ateliers used stencils so that a particular manuscript displayed a uniform style.

R – British Library – The Maastricht Hours STOWE MS. 17 f. 31r – Liège – early 14th c.

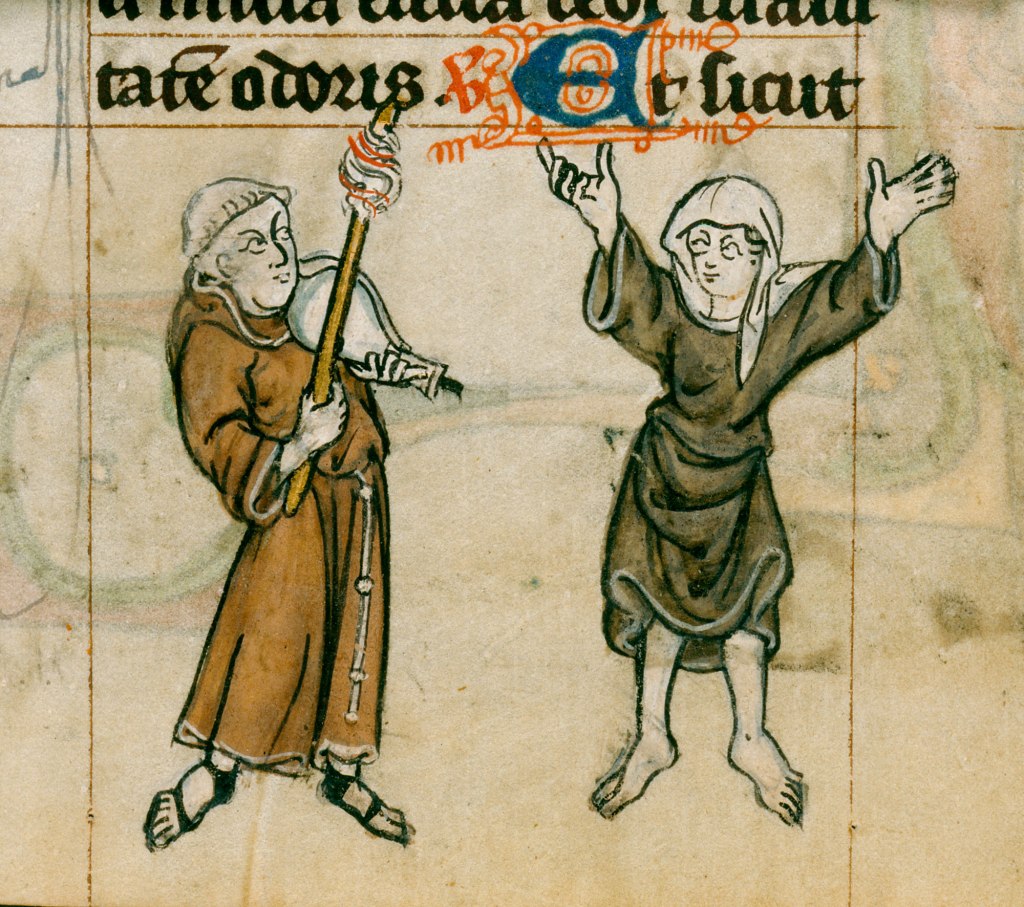

The act of dancing becomes even more bizarre when a nun and a Franciscan friar overstep their religious integrity. At first glance the friar appears to play a fiddle. A second glimpse makes obvious that he is playing a somewhat stranger instrument; a fireplace bellows with a distaff as bow. Try imagining the sound of distaff striking along the bellows. But the ‘music’ obviously pleases the dancing nun tremendously seeing that she raises her arms high into the air and, disregarding all conventions she hitches up her habit to be able to dance more energetically. Not only are her feet bare but she also displays her uncovered knees which, to say the least, is not exactly what one would expect from a nun. And looking at her disorderly veil and loosened hair it would appear that she has been dancing for some time. The artist heightens the revelry even further. The couple look intensely at each other; there is no doubt about their amiable focus. Call the image humorous, a mockery or a parody but for a citizen of the Middle-Ages the message was evident.