In illuminated manuscripts, especially from the 13th century onward the bas-de-page, that area under the text at the bottom of the page was embellished with a wide variety of images. The bas-en-page images were unframed and may or may not refer to the written text. They could be whimsical, satirical, mocking, mischievous, sexual or downright rude. Every imaginable image was possible; rabbits, unicorns, snails, horses, birds, knights, damsels, musicians and dancers together with the most fantastic hybrids and awesome grotesques. Dance images rang from realistic dancers, to hybrid dancers, dancing animals, jongleurs, morris dancers and mummings.

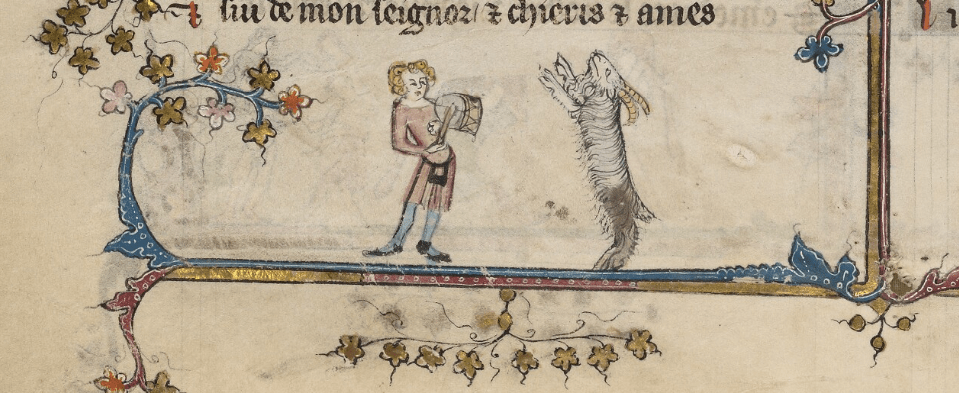

ill. 2 – British Library – The Maastricht Hours – STOWE Ms17 f.112r – Liege

ill. 4 – British Library – The Maastricht Hours – STOWE Ms17 f.49r – Liege

The four images shown above give some idea of the diversity of the dance motifs. Illustration 2 presents a jovial scene of a playful dog wearing a hooded cape, a nimble man and a leisurely damsel accompanying their dancing. And then there is the image of the hybrid nun, with her skirt lifted to display her bizarre paws, dancing resolutely at the sound of the bagpipes played by an equally bizarre bishop. These images come from The Maastricht Hours, an impressive manuscript made, presumably, for an aristocratic lady in the early 14th century.

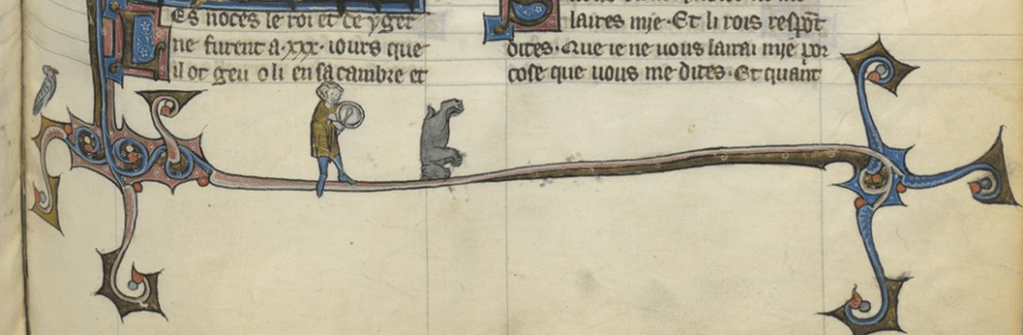

A favourite bas-de-page motif was the performing animal. Dancing monkeys were immensely popular. The two monkeys (ill.3) illustrating a devotional Book of Hours (MS.W.88) form an elegant dance couple. The monkey on the right is especially graceful, looking less like a monkey than the more robust high shouldered partner. The well poised monkey has style, presenting its hand with courtly composure. One might wonder if these monkeys are mocking an aristocratic court dance. One might also wonder why these odd monkeys are decorative images in a book intended for devotion. But where these dancing monkeys can be seen as mockery the image of the monkey trainer (ill.5), with rope and baton in hand, commanding the human tumbler to do tricks is satire. The world is literally turned upside down.

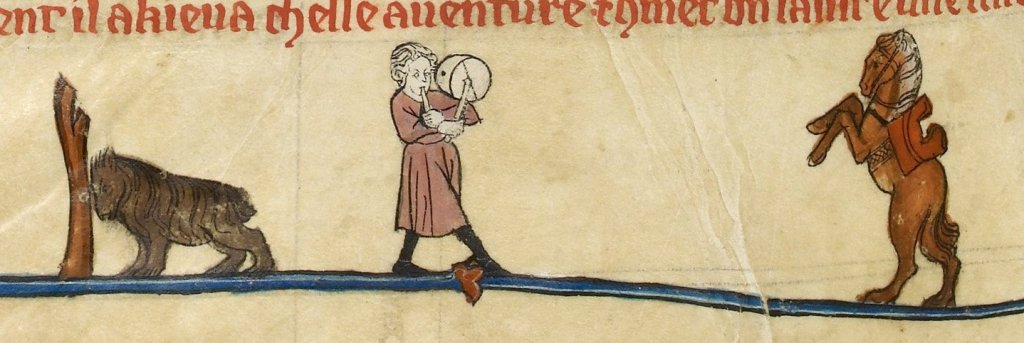

In the same secular manuscript as the image of the monkey trainer, Lancelot du Lac, we find a performing horse prancing to his trainer’s flute and tabor. To my mind this is an extraordinary horse standing even straighter and rearing considerably higher than a trained circus horse. To the left is another animal knocking his head against a tree trunk. Judging by the paws and stripes I would guess it is a tiger. All these figures could be part of travelling street entertainment seen by the enterprising Lancelot during his adventures.

Next in popularity were the dancing dogs but there was also a fair spattering of dancing goats, bears, hares and I have even seen one or two light-footed unicorns pass by; and this without taking into consideration the multitude of dancing hybrids. These dancing animals appeared both in sacred and secular manuscripts. That similar images appeared in both types of manuscripts came about by the growing demand for books by the aristocracy. The production of manuscripts therefore gradually transferred from monasteries to professional workshops and with this transition the overlapping of motifs became an accepted practice. The most favoured secular manuscripts were the Arthurian Tales, Adventures of Alexander and Le Roman de la Rose.

Below you will find a slideshow with four images of dancing animals. The first two images, come from Romance of Alexander, a unique Flemish manuscript housed in the Bodleian Library, Oxford (Bodl.264). The third image, a bagpiper and his dancing dog come from the same devotional manuscript, a Book of Hours, as the monkey couple shown above; either the artist or the patron or both enjoyed the lightheartedness of dancing animals. Or perhaps these images provided an amusing interlude between the long periods of devotional contemplation. The last image, from an Arthurian Romance probably made in St. Omer between 1270-1290, shows a trained bear performing his tricks under the watchful eye of his master beating the rhythm on his tabor.

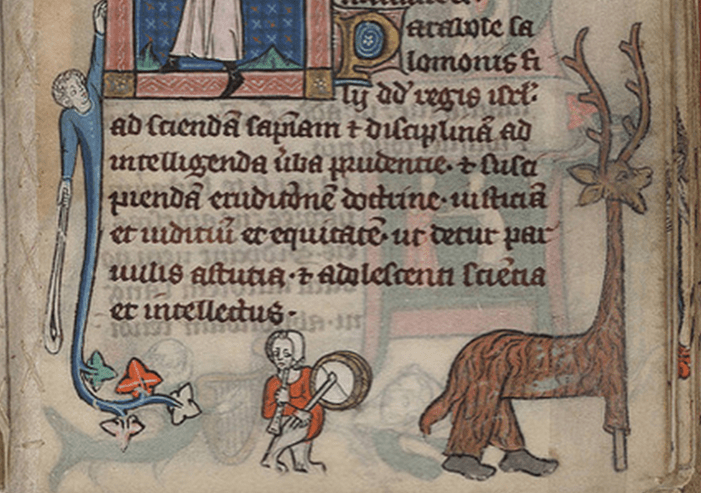

All animals are not what they seem to be. Take a close look at the good-natured stag illustrated below. Under that jolly expression there is something rather strange. Halfway down the front of his body, surrounded snugly by hide, you can just see two eyes, a nose and a mouth. This merry stag also has very peculiar hooves; he is wearing black shoes and has a staff as substitute for his fore-legs. It goes without saying that animal imitations were a popular form of entertainment in the medieval world. This black-shoe stag and his musician is a bas-de-page illustration from the secular manuscript Romance of Alexander. The Arthurian Romance, mentioned above, has an image of a stag walking erectly on his hind legs (ill. 8). This stag is draped in a cocoon-like garment complete with opening through which the actor’s face emerges. The next illustration (ill.9) is taken from the Rothschild Canticles, a devotional manuscript full of surprises. Who would expect to find an acrobat, especially one as depicted in illustration 1 (top of the page) in a sacred manuscript? No less surprising is to find a stag with a giraffe like neck and a mystifying tail. A very long stick supports his elongated neck carrying perpendicular antlers that continue halfway up the margin. And not to forget the stags hind quarters which look more like a pair of brown britches supporting two bare feet. Images of performing animals were commonplace in both sacred and worldly manuscripts.

Below ill. 8 – Arthurian Romance BnF fr.95 f.261r – St. Omer (probably)

Below ill. 9 – Rothschild Canticles MS 404 f.175r – Beinecke Rare Books and Manuscript Library

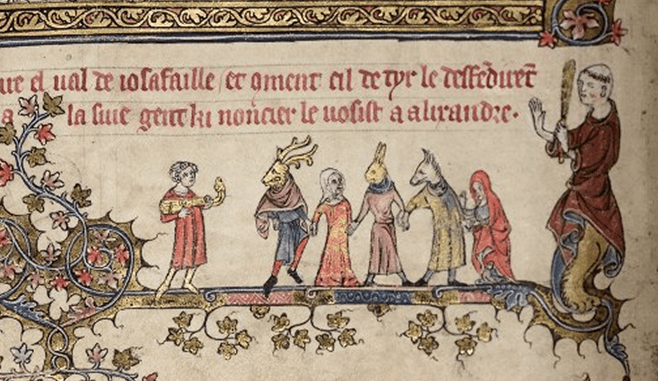

A most astonishing and diverse series of bas-de-page illuminations are to be found in the Romance of Alexander a manuscript, created in the workshop of the Flemish illuminator Jehan de Grise in the first half of the 14th century. Under the written text there are quite a few images of dancers, musicians and many strange looking figures adorned with masks. These are mummers who at Christmas time, disguised themselves as animals, travelled from house to house, gave performances, sang a song, told jokes and after enjoying some refreshments continued on their way. Illustration 10 shows two women and three mummers, a stag, a hare and a boar, line dancing. Fascinating is that the monk, a giant in comparison to the other figures, beckons the dancers to stop with their frivolous amusement; this can be none other than a moral message.

Mumming was a traditional folk festivity and customarily mummers were costumed village folk. Illustration 11 depicts two line dances, one of mummers and the other of dignified ladies. Peculiar that these women wear gowns appropriate for court ladies and that the mummers carry purses, bear daggers and wear glorious capes decorated with coats of arms. This is not exactly the dress one would expect from village folk. Could this illumination represent the aristocracy imitating and enjoying folk traditions?

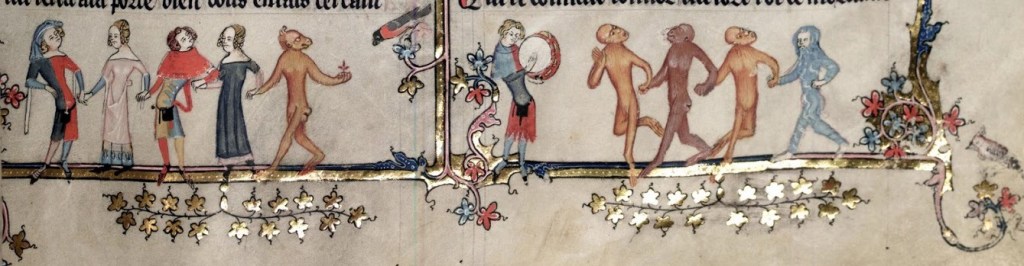

The last illustration (ill. 12) is somewhat puzzling. What are we looking at? On the left side two noble couples are dancing. They all hold hands as does the monkey joining them at the end of the line. That monkey stands like a man, imitates a man but he is not a man disguised as a monkey. One look at his bottom reveals his true identity. He is holding something in his hand, possibly a fleur-de-lis,* and offers it to a very interested bird. On the right there is another line dance; this time a musician playing a tambourine accompanies a line of three very human looking monkeys and blue hairy wild man. There are two very similar monkeys; both turn their heads identically to the left. The line aims to move forward but, this cannot be, the third monkeys legs are all tangled and face wrong way. The centre monkey nevertheless marches swiftly forward as does the blue man. This may be just a burlesque image or perhaps the dancing monkeys are symbolic of court life. Either the artist has drawn an amusing illustration or a shrewd parody. The puzzle remains unsolved.

* fleur-de-lis – the heraldry symbol of the French monarchy and also used by the House of Plantagenet. It appears on various miniatures throughout the manuscript.