What is the difference between a popular dancer and a respectable dancer? And is there a similar distinction for musicians? Today this question might seem trivial but in the Middle-Ages there was a sharp differentiation between popular and respectable music and dancing. In my previous posts I have written about the role of the musician, often a jongleur, who played a stringed instrument, had a low social status and lived on the outskirts of society. The dancer, chided for her lascivious movements by both the church and intellectual society, suffered the same fate. This non-acceptance resulted in popular musicians and dancers invariably appearing on the outer edges of illuminated manuscripts. Notwithstanding there are instances where dancers and musicians were considered respectful. These, often biblical or religious figures, appeared in the miniatures of illuminated manuscripts whose framed borders protected them from the perils of the world beyond. This divided world is illustrated on the miniature shown below. The popular musician, playing unworthy music, is standing in the margin balancing on a platform while the monks, singing respectable music, are standing sturdily within the enclosure of the initial. And this very same initial is further safeguarded from the outside world by a strong rectilinear boundary.

This illustration is typical of the illustrations found in the illuminated manuscripts of the Low Countries and elsewhere. Monks singing psalms, angels in a celestial dance and personages from the Bible are frequently drawn within miniatures and very often specifically placed inside an initial. In contrast the jongleur, the musician, the dancer and other less-respectable figures are destined to remain in the periphery.

King David, portrayed as dancing before the Ark of the Covenant or as a musician playing his harp or striking the bells often in combination with the slaying of Goliath, is a recurring subject. A Psalter housed in the Morgan Library has a leaf showing David seated on his throne playing his harp. The lower section of the Beatus initial shows David decapitating Goliath. The action of these biblical moments, even the gruesome ones, takes place within the initial B which is safeguarded by a defined boarder. The respectability of the music that David plays is never doubted. On the same level as the slaying of Goliath a dancer and musician are performing on a plateau, apparently oblivious of the world inside the shielding miniature.

Even though the quality of the above illustration is poor the dancer’s voluptuous movements are obvious. A closer look reveals that she is holding small musical instruments in her hands; presumably as musical accompaniment for her partner. The artist has drawn the folds of the gown so explicitly that her skirt looks slightly transparent thus allowing the shape of the legs to come to light. That combined with her arms energetically placed above her head, and the forceful forward thrust of her hips leaves no doubt to her enticing style of dance. To top all that the string player displays his uncovered leg shamelessly. And that all takes place just outside an initial encasing King David.

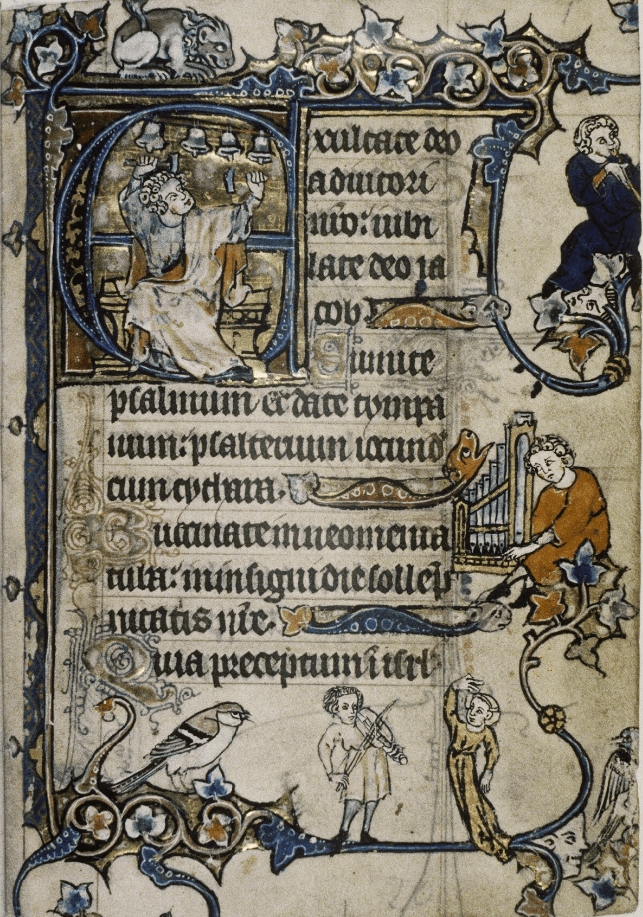

A portable Benedictine Psalter made in Ghent in the early 14th century has a similar narrative. In Douce 5 (left illustration) King David, once again enclosed in the Beatus initial, is playing his harp. In the lower level David is beheading Goliath. The frame surrounding the text is filled with drolleries; birds, a nude man suspended in the frame, dragons, protruding faces and on the lowest ledge a dancer displaying her acrobatic dexterity. In the adjacent illustration (Douce 6) King David is seen striking bells. Here, as in the previous example, David is playing righteous music applauded by the church and intellectual society. That does not apply for the musicians surrounding the text and even less for the dancer and musician, standing near an over-sized bird, at the very bottom of the page. They are entertainers, makers of popular amusement, and are distanced from the biblical King David.

R -Bodleian Library MS Douce 6 f.001r – Psalter Flanders, Ghent c. 1320-30

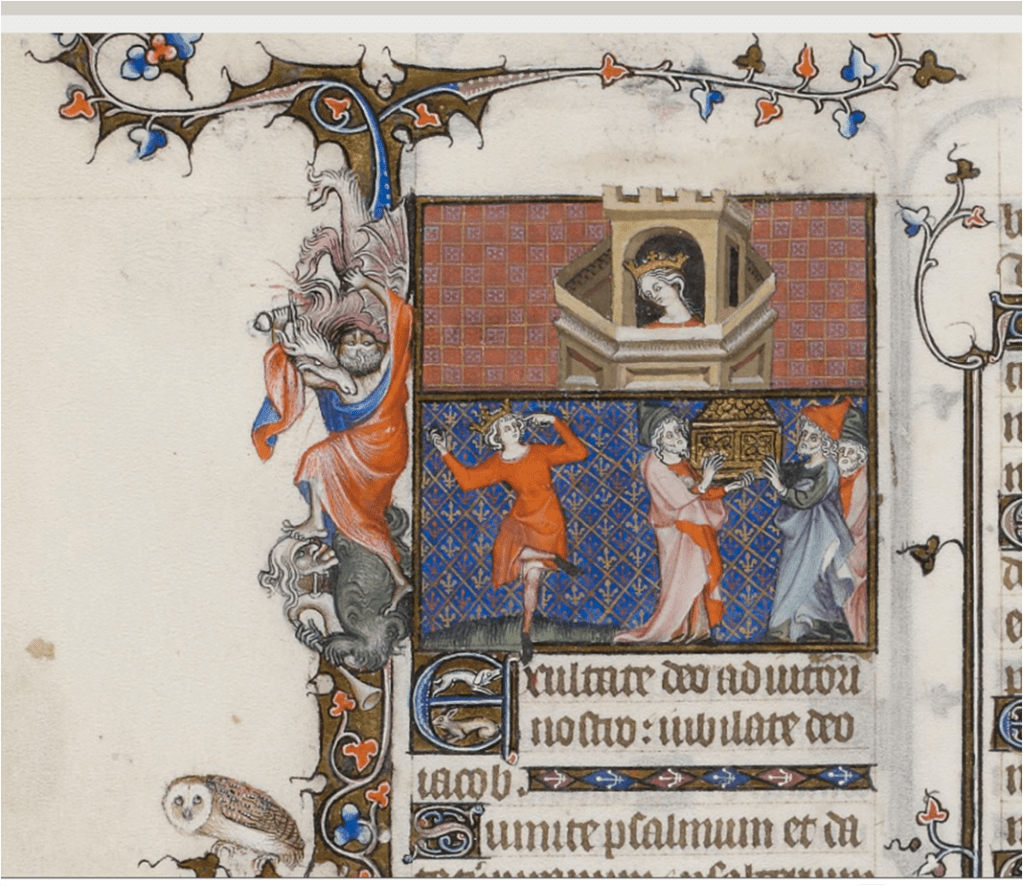

Dance is mentioned in the Bible on various occasions. The dance around the Golden Calf (Exodus) can be classified as bad dance, just as the dance by the daughter of Herodias, often called Salome, is shameful. On the other hand King David, dancing ‘before the Lord with all his might’ (2 Samuel) when celebrating the recovery of the Ark of the Covenant, is performing an honorable dance. The Belleville Breviary, containing miniatures of David dancing, has two volumes: one volume for summer prayers and the other for winter prayers. The illustrations are attributed to the French illuminator Jean Pucelle and his workshop, and although not rightly from the Low Countries one of the artists in his workshop, a certain Maître de Cérémonial de Gand was a Flemish countrymen. And besides that, these illustrations are plainly too good to miss.

R – Bréviaire de Belleville – BnF Latin 10484 f. 40r (summer) – detail 1323-1326

Both miniatures are enclosed within columns of text. Each one is quite small taking no more than a quarter of the length of the column. Both show a young king rejoicing. The ‘winter’ David is light footed, his bent leg lifted to hip height as if he is about to hop or jump. His is a joyful, vibrant dance of a young frolicsome man. The ‘summer’ David is more earthbound. This illustration gives little sense of movement. Rather David appears to step into a fixed pose and, if you could think away the crown, looks more like a jester than a king. In both miniatures he is fully attired but according to biblical text David was scantily dressed. The elated king’s dancing, as the miniatures show, lacks the necessary royal decorum required from a man of his status. David’s wife Michal was abhorred by this disgraceful display; in both miniatures we seen the appalled Michal looking out of the window. David’s dance, even though Michal objected, is sanctified by the church and therefore fittingly placed within the text, bound by the security of the enclosed frame. One final comment about the ‘winter’ David; on the margin side next to David appear gruesome monsters with the most hideous faces. These ghastly creatures are exactly where they belong, on the outside of the text. On a lower platform the wise owl, his worried eyes cast upwards, rests indecisively.

The Morgan Library holds the uniquely decorated Psalter-Hours of Guiluys de Boisleux. The above illustration shows the top half of a full-page miniature. David on entering the city of Jerusalem plays a portable organ. He is surrounded by men and women dancing and musicians playing trumpets, viols, horns and pipes. It is a festive occasion. The sphere is exuberant. David and the crowd express great joy which the artist has made unmistakably evident in the way he has portrayed their lofty movements and jubilant faces. The sheer ecstasy of both dance and music express absolute devotion. King David’s ecstatic dancing, dancing ‘with all his might’, is an example to all. Any image of this biblical episode has, according to medieval convention, a rightful place within the framework of the written text.

Having established where one would expect to see images of King David, I came across a 13th century Bible showing a youthful, sprightly David leading a row of musicians and two men carrying the Ark of the Covenant. David and his group are at the bottom of the page – bas de page- parading along a decorated border; the spot generally reserved for the popular artist. In contrast to the detail of the images shown above, this row of merry-men is a simple procession of outlined figures to which a little color has been added. Straightforward as this marginalia is, the face of each character is expressive and each has a cheerful disposition.

The artist draws King David moving; with a little imagination it is practically possible to envision him taking the following step. The musician playing the bagpipes also appears to move. He looks as if he is running or making small leaps to catch up with the group.

In the Middle-Ages there was a clear distinction between popular and respectable music and dance. Artists decorating illuminated manuscripts were well aware of this distinction. But as with any convention there are exceptions; the dancing David in this Bible being one.

If you wish to have a closer look at Douce 5 and Douce 6 follow this link.