Neither music nor dance was considered respectable within the Medieval Christian Church. The classical Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle appreciated the science of music but regarded the professional musician with contempt and dancing fared no better. Their ideas influenced the early Church Fathers to the point where music and dancing were seen as corrupt, distracting Christians from their spiritual well being.

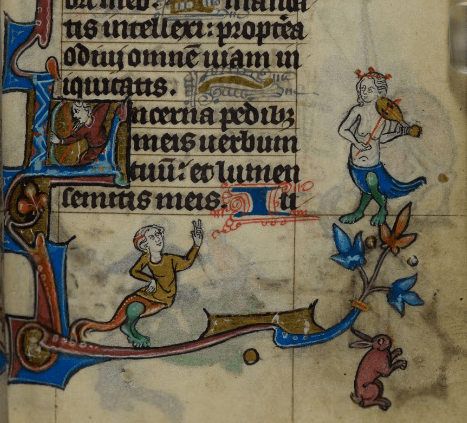

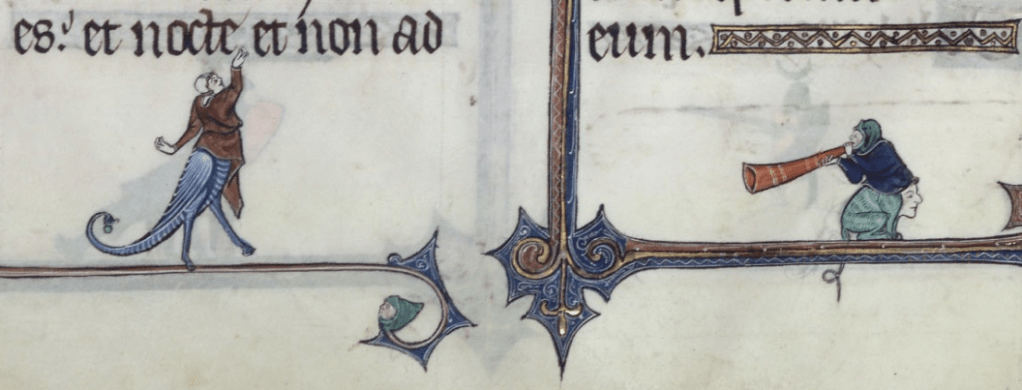

Artists, especially the wandering artist, were treated as the lowest of the low. Jongleurs, a medley of musician, tumbler, animal trainer, dancer and all-round entertainer were outcasts, living outside of the social order on the fringe of society. At times they performed at court or in churches but were mostly associated with taverns, brothels and street entertainment. Their music, according to the Church, corrupted the populace and invited dancing which according to the early church father Arnobius, lead audiences ‘to abandon themselves to clumsy motion, to dance and sing …. raising their haunches and hips, float along with a tremulous motion of the loins’. Another church father John Chrysostom, Bishop of Constantinople, spoke about music and dancing in the same breath as he spoke about Satan, advising his flock that ‘it is quite indecent and disgraceful to introduce into one’s home lewd fellows and dancers, and all that Satanic pomp…’, adding ‘Where there is dancing, there is the devil’. No wonder that musicians and dancers are always obliged to inhabit the margins in the illuminated manuscripts. And if that was not enough dancers and musicians were often the subject of satire, even ridicule, portrayed as grotesques and hybrids.

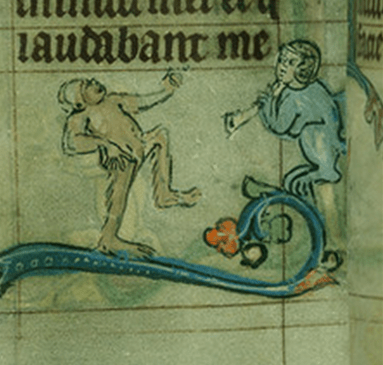

Hybrids, a half-human figure merged with all sorts of fantasy elements, were a common feature of 13th and 14th century illuminated manuscripts. Why were dancers and musicians represented in such a odd way? It is possible that the illustrator was just having some fun, adding a touch of comic relief to the religious texts. This, without doubt, is a probable explanation but there is more to this story. Dancers twist and turn, make grotesque shapes which, according to the church of the time, were physically offensive and caused moral degradation. Christians believed that the human body was created in the perfect image of God. Christians should aim to be poised and carry themselves with appropriate ease and devotion. Dancers lacked that required poise with their incessant convolutions of the body. They were grotesque, obscene, deformed and often compared with the foolhardy antics of monkeys. Dancers, according to medieval thought, defiled the human body. The musician, the hybrid dancer, the grotesque dancer, the dancing monkey became notorious marginalia. However amusing, comical or brash these marginalia were they constituted a sincere warning to the good Christian.

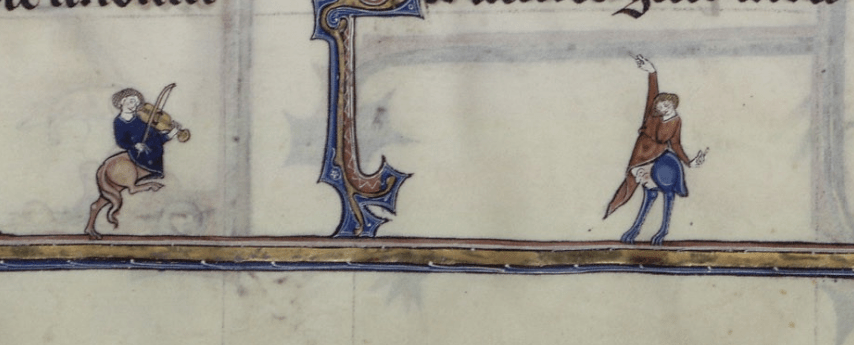

The hybrid musician and dancer shown above come from a small Book of Hours originally used in the diocese of Cambrai. Page after page is decorated with charming scenes ranging from cooking, fishing to music making and dancing. The Walters Art Museum where this manuscript is housed gives the following information; ‘drolleries amused the faithful during their prayers, whilst showing scenes that worked as metaphors for the soul fighting the vices’.

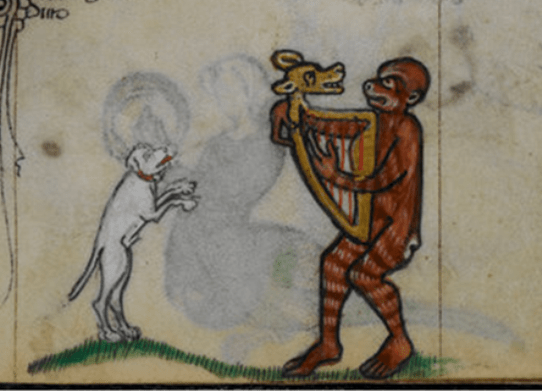

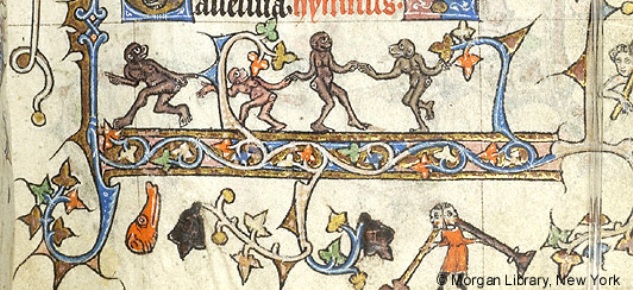

Devotional books, contrary to what you may expect, were not exempt from visual down-to-earth humour. The margins were full of fun, playfulness, parody and sensually naughty, even bawdy scenes. Monkeys participated fully in this marginal mockery. Monkeys were seen as devilish and were regarded as ugly. They embodied the worst aspects of human nature symbolizing malice lust and greed. The monkey, it was said, imitated human action. Monkeys in illuminated manuscripts fight, hunt, joust, can play chess, play bagpipes and of course monkeys can dance. The monkey image was designed to mock human behaviour and was, to the medieval man and woman, a reminder of our own simian side. However amusing we find these monkeys today, they were intended to highlight the frivolity and folly of human actions.

C – Walters Art Museum MS. W.85 f.3r (detail) Book of Hours – Ghent c. 1300

R – British Library Maastricht Hours Stowe 17 f.245 (detail) Liege early 14th c.

The monkeys in the illustrations above all imitate human behaviour. They are drawn on the very spot where one usually expects to see a dancer or musician. In the first illustration the artist has simply outlined the figures giving little attention given to accuracy or detail. The naked figure, with those enormous paw-like feet, looks like a monkey yet there is a marked resemblance to a human figure. This raises a few questions. Is this in fact a human looking like a monkey or monkey that looks human? Or perhaps the artist cannot draw a recognizable monkey. For simplicity’s sake let call the figure a monkey. Totally absorbed in the dancing, this crude figure, throws his back leg brazenly into the air. Why has the artist chosen for the back leg? We can only guess at the answer but if you consider that the figure is naked then the artist would have shown more discretion to lift the front leg. This coarse monkey, together the equally crude musical hybrid companion ridicules the medieval entertainer.

The next illustration hints at the same problem. Is the figure a monkey or not a monkey? This naked figure, possibly drawn by the same artist as the previous illustration, does a handstand with a zest and brilliance that would do any medieval tumbler proud. One wonders what the two ladies, safely contained within enclosed frames, are thinking about this exuberant display of acrobatic undress. The last illustration depicts a grumpy looking musician monkey, possibly a caricature of jongleur, urging the unfortunate dog to dance. In the two illustrations below monkeys are dancing and capering around. In the top illustrations we see them dancing in a semi-circle and below burlesque monkeys perform a line dance. Would the two-faced musician, a layer lower, refer to ludicrous expression on the monkeys faces?

Monkey imagery survived the test of time. In the art of the Low Countries the monkey metaphor moved from the illuminated manuscript to panel and easel painting. Singerie, an art form where monkeys behave and dress as humans in realistic situations became a specific genre of art in the 17th century. Jan Breughel the elder, the brothers David and Abraham Teniers and Ferdinard van Kessel specialized in these very fashionable satirical paintings. In van Kessel’s painting, which recalls the work of Pieter Brueghel the younger, the monkeys imitate village folk drinking, dancing, urinating, eating and in the right hand corner we meet, yet again, the familiar dancing dog.

If you wish to take a closer look an early 14th century Book of Hours The Walter Art Museum offers an online version of MS. W.85.