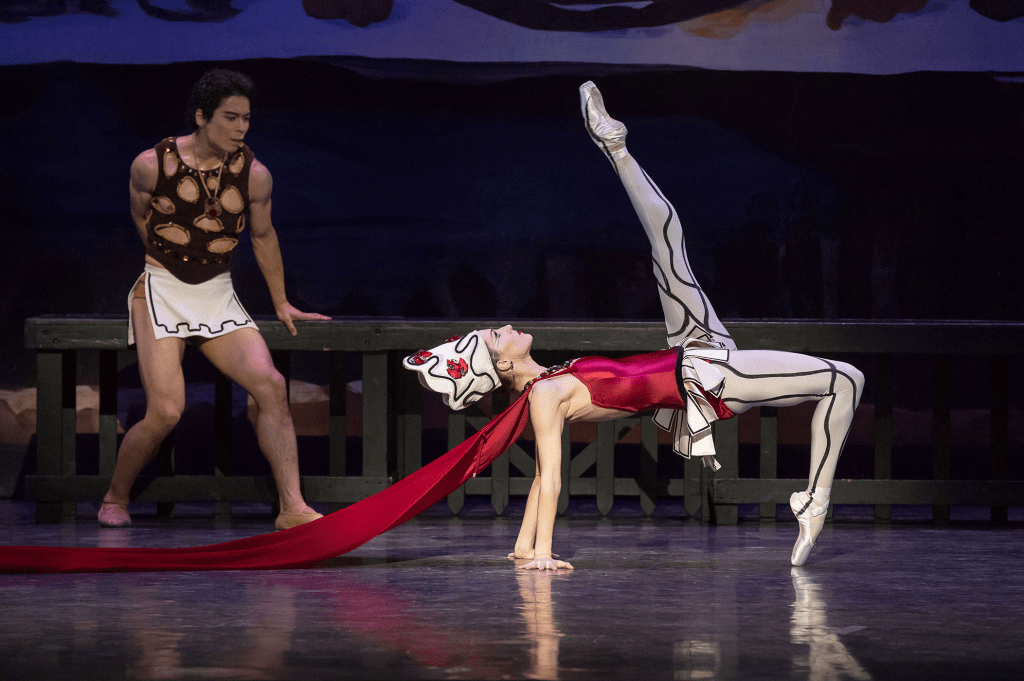

Dance technique today, whether classical, modern or urban, embodies movements derived from acrobatics. High leg extensions, the splits and acrobatic lifts have become part of the dance vocabulary. The great choreographer George Balanchine embraced acrobatic movements into his magnificent ballets. Twentieth century choreographers have followed suit and contemporary break dancers do no less when they revolve over the ground and spin on their heads. In my search through 14th century illuminated manuscripts from the Low Countries I found images of dancers performing the same type of acrobatic movements with which we are familiar today. This blog takes a closer look at the image of medieval acrobatic dancer and draws a few parallels with our own time.

Morgan Library and Museum MS M.730 f.224v Arras 1243-46 – detail

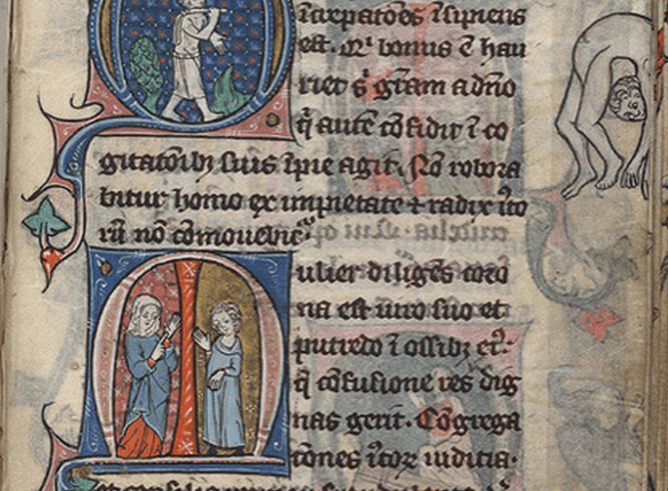

Morgan Library and Museum MS M.754 f.10v St Omar 1320-29 – detail

John Gleese – Ministry of Silly Walks – Monty Python – 1970

Walters Art Museum Ms W.88 f.60 – French Flanders – early 14th c. – detail

Bodleian Library MS. Bodl.264 f.90r – Romance of Alexander – Flemish 1388-44 – detail

Break dancing – elbow freeze

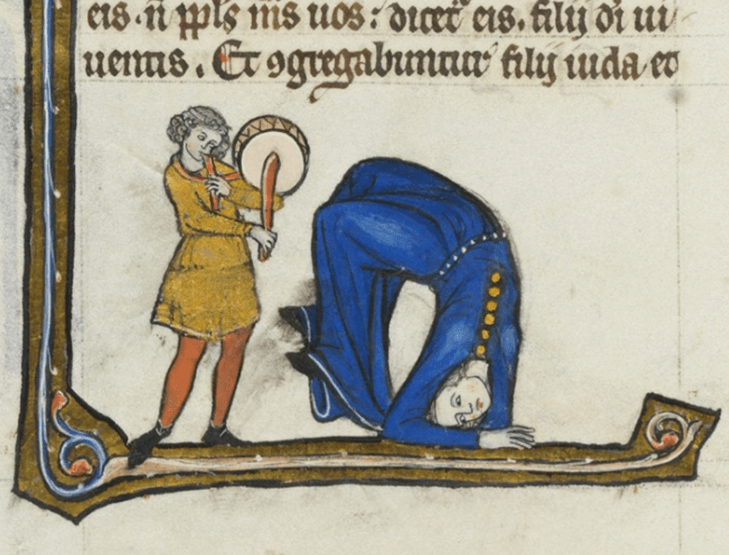

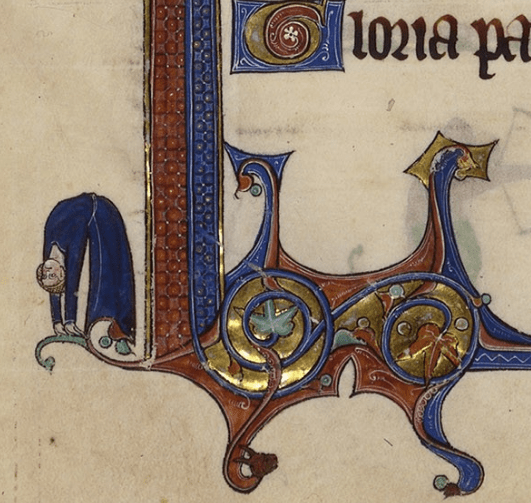

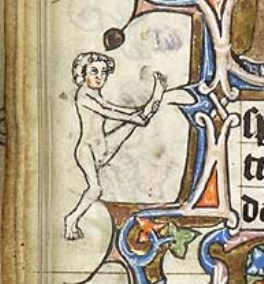

Dancers inhabit the margins of illuminated manuscripts. The two nude dancers, shown above, come from manuscripts intended for private devotion. It is still a debatable question as to why nude figures should appear in manuscripts intended or commissioned by clergy and the upper classes of society. But whatever the reason may be, these dancers are most certainly professional entertainers and can throw their legs as high any contemporary chorus girl or, for that matter, as the high-kicking John Gleese. The dancers in the second row perform eye-catching handstands not dissimilar to the contemporary break dancer. Remarkable is that the image of the dancer in orange comes from a devotional Book of Hours and the blue dancer is an illustration from the secular manuscript Romance of Alexander. Apparently, in 14th century art, artists made no distinction between the marginalia intended for sacred or for profane manuscripts.

The elaborately decorated devotional manuscript, The Rothschild Canticles, produced in Flanders and the Rhineland around 1300, contains drawings of three exceptionally agile nude performers. These acrobatic dancers are amazingly nimble and perform stunning capers.

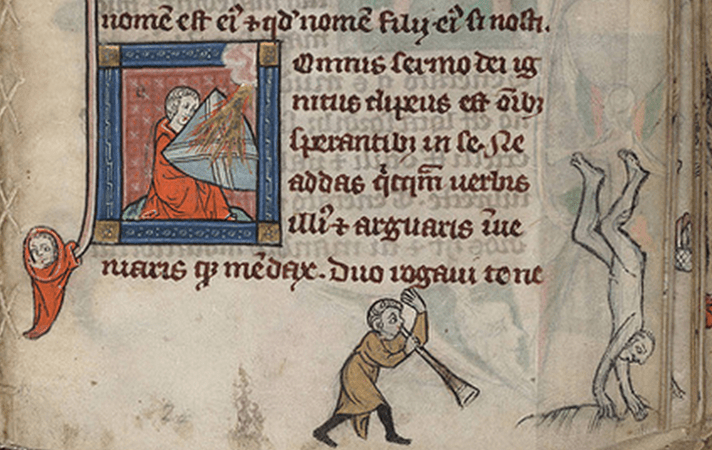

Folio 155r

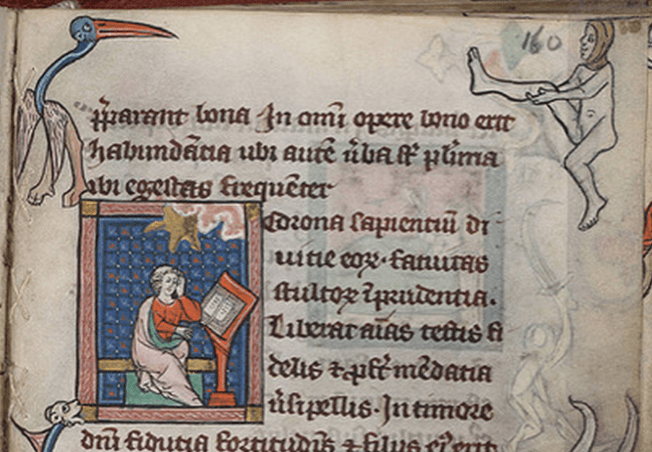

Folio 160r

Folio 167r

In folio 155r an anonymous artist has drawn a contortionist in an extreme back bend on the same leaf as a miniature of the Visitation. A very strange combination to say the least. In the next folio a poet is pondering over his work. Meanwhile in the right top corner a performer throws his leg high into the air whilst being keenly observed by a hybrid long beaked bird perched on beast-like paws. And in third illustration a worried looking nude figure performs a handstand to the melody of the enthusiastic musician’s shawm. The artist has drawn each acrobatic dancer in a basic black outline with a minimum of detail. The high-kick dancer wears a colored hood but apart from that the three figures are left blank and that forms a stark contrast with the colored and far more detailed framed miniatures on the same folio. Why this contrast? Perhaps part of the answer is that in the Middle-Ages jongleurs, who were both musicians and dancers, had a disreputable status. They led a wandering existence, had a low social acceptance and lived on the outskirts of society. To draw them nude only emphasized their shady character. Jongleurs were condemned by the church. Clerics instituted a ban against them because their way of moving was considered illicit and obscene. They, both in daily life and in the manuscripts, were destined to abide the outer borders.

Le Jongleur of Notre-Dame, a 13th century French poem, tells the story of a jongleur turned monk. He has no gift to give the Virgin Mary except the gift of what he does best, playing music and dancing. He dances for the Virgin Mary with all his might. The Virgin is delighted by the humble jongleur’s righteous performance. He had given her his greatest gift. She even asks a passing angel to pass the poor man a towel to wipe his brow. A wonderful story illustrating a more positive view to dancing which here, contrary to the general mindset of the time, is not considered grotesque, illicit or defiling the image of God.

The above image is the first known image of Le Jongleur de Notre Dame and, if I do not take Egyptian and classic art into consideration, is a very early image of acrobatic dance. The anonymous artist has drawn the jongleur in a exceedingly awkward position. I wonder how he can possibly lift his head, whilst in a deep back bend, to such an extent that we can see his entire face? And this is not the only example of such an anatomically improbable position. In the Maastricht Hours there is an image of a acrobatic dancer practically rolled up performing a back bend combined with what looks like a twist of the upper torso. Has the artist deliberately drawn such a physically unfeasible position? Less improbable are the contortions shown in the Biblia Porta and the Psalter-Hours shown below. These performers are stunning and anatomically more correct though the extreme back bend of the dancer balancing precariously on a vine is quite unsettling.

Right – Bibliothèque nationale de France – BnF Ms Latin 14284 – Psalter Hours – use of Thèrouanne – c. 1280 – detail

The back bend, once the field of jongleurs, has been incorporated into contemporary choreography. Acrobatic movements are no longer stunts to astound an audience but they have developed into an intrinsic part of the choreographic language. In The Prodigal Son, by George Balanchine, the ballerina ‘walks’ across the stage floor kicking her legs high into the air. When this ballet was first performed in 1929 Balanchine’s use of movements outside of the traditional ballet technique astonished audiences and critics alike. Today, as the work of contemporary Dutch choreographer David Middendorp illustrates, acrobatic dance is an integral part of dance performance. Actually no different than in the Middle-Ages.

Right – Flirt with reality – David Middendorp – 2019

Go to the following link if you wish to explore the magnificent Rothschild Canticles