Perusing through many illuminated manuscripts I noticed that the same or very similar motifs regularly appeared. One would expect rabbits, unicorns, dragons, monkeys, grotesques and jugglers to make frequent appearances but to repeatedly find dancing ladies standing on the shoulders on their musical companions was rather surprising.

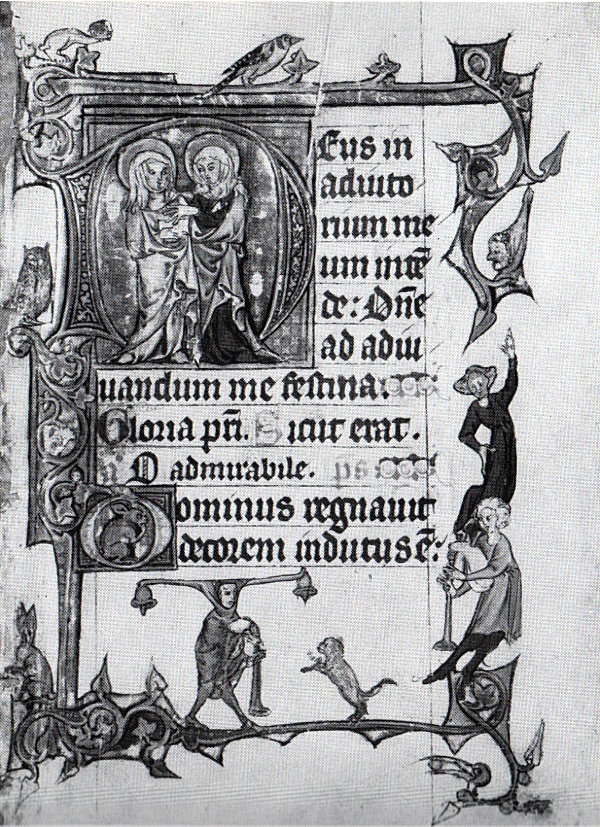

Maastricht Hours – Stowe 17 f.31r – detail

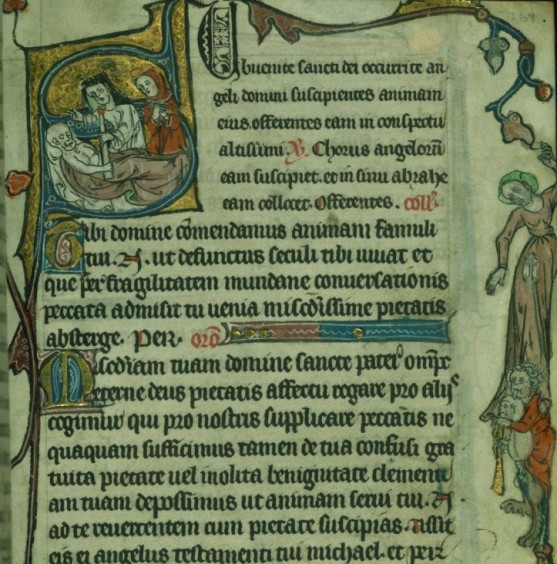

Book of Hours W.90 f.61v – detail

Book of Hours Ms B.11.22 f.7r – detail

Walters Art Museum – Book of Hours W 90 f.61v – French Flanders, early 14th century

Cambridge MS B.11.22 f.7r – Book of Hours with calendar – Flanders c. 1300

The dancer perched on the musician’s shoulder motif occur every so often in manuscripts produced in both the Low Countries and those made in Paris and the British Isles. Whether from the Low Countries or elsewhere these dancers and musicians are always placed on the outskirts of the page and they have very little or no direct relation to the written text. Take, for example, one of the earliest Flemish Book of Hours, the Ghistelles Hours, which was probably made for John III Ghistelles and his wife Margaret of Luxembourg around 1300. Even though I can only show you a black/white image, this folio clearly demonstrates that the great activity taking place all around the boarder has a limited relation with the biblical illumination of The Visitation which is shown in the historiated initial ‘D’. I use the word ‘limited’ because the rabbit on the lower left might be a suggestion of fertility and the owl on the outer ridge next to the main illumination would most likely suggest wisdom. But the meaning behind the dancer and musician is far more puzzling. Here we have Saint Maria and Saint Elizabeth meeting each other at a most profound moment in their lives only to be surrounded by musician playing a long trumpet and an agile dancer whose main interest is directed towards a musical fool and the sprightly cat. Dancer and musician appear totally oblivious of the exceptional event taking place. Only the wise owl, seated on the same level as the miniature, appears to be aware that he is present at a miraculous event.

Manuscripts intended for private devotion were illuminated with both profane and religious images. The illustration, shown below, taken from a Psalter-Hours housed in The Walters Art Gallery demonstrates this. In the main miniature, the initial ‘S’, a dying man is receiving the last rites from an abbot. Juxtaposed to this emotional scene is a strange hybrid musician standing on what look like lions paws, playing the bagpipes whilst supporting a rather long dancing lady on his shoulders. The artist has not drawn part of her raised left arm. I wonder if, when drawing the dancer, he suddenly realized that the scribe had left insufficient space in the margin to complete the figure. Cropping, I presume, became the obvious solution. And those bagpipes are rather curious; under the musician’s face a second funny face protrudes. Notwithstanding that the dancer performs elegantly in her flowing dress, she and her partner have little more than a decorative function.

Marginalia rarely related to the text nor were they derivative from biblical sources. As a general rule the miniatures placed within the text columns came from biblical sources whilst the artist had a free-hand in inventing the marginalia. In the main miniature, shown below, one of the most shocking incidents in the New Testament is taking place; Stephan is being stoned to death. Next to this horrific scene the artist has drawn a musician playing his bagpipes whilst the dancer stands poised and upright on his burdened shoulders. Both have turned their backs, perhaps, walking away from the appalling occurrence. For all one knows the artist has deliberately given the dancer that perplexed expression and the musician that downcast posture as a reaction to gruesome goings-on.

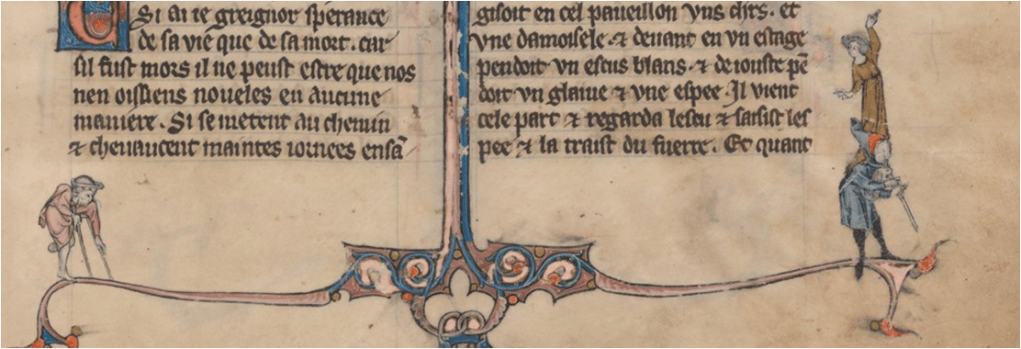

It was not uncommon that both liturgical and secular manuscripts were decorated with the same type of image. During the mid-thirteenth century the secular manuscript, often written in the vernacular and favoured by nobles and aristocracy, emerged. In the Low Countries the Arthurian Romances was in great demand. The Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library holds the Arthurian Romance generally named ‘Lancelot’ of Yale. Composed in Northern France probably in the workshops of St-Omar or Tournai, this late 13th century manuscript has a dancer with musician motif not unlike those appearing in liturgical manuscripts. At the top of the right column there is a framed double miniature relating to the tale of Lancelot and the bottom of the page – bas de page – a dancer stands on the shoulders of an amusing musician who is blowing his bagpipes so enthusiastically that his cheeks inevitably inflate. The inquisitive lady appears to turn her body sharply, startled perhaps, by the disabled man on the opposite of the border.

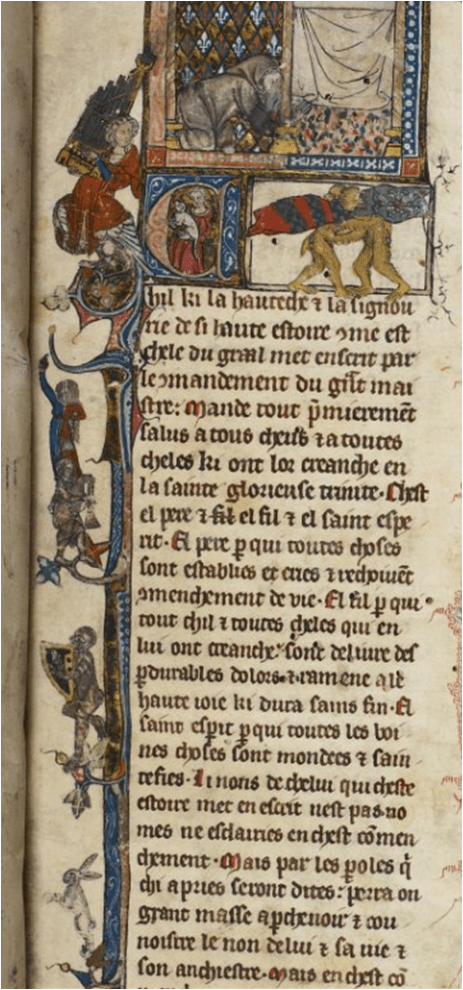

For the last example the opening page of the Lancelot Grail Prose Cycle, a secular manuscript once owned by the king of France Charles V (1338-1380), now housed at the British Museum. This folio is a celebration of illustrations. Apart from the two magnificently detailed miniatures, there are decorative initials and a border inhabited by hybrids, angels, birds, rabbits, a tournament scene with knights and trumpeters and a dancer standing on the shoulders of a musician playing the bagpipes. They are just one of the many meticulous marginalia and you have to look carefully to find them. The stance of the dancing lady, with her hips gently protruding and the top of her body curved slightly backwards, is not dissimilar to the women and saints found in Early Nederlandish painting. As in most manuscripts the couple are on the outer edge of the folio poised on a flowery vine. More unusual is that the dancer and musician are, as the couple in the ‘Lancelot’ of Yale manuscript, turned in opposite directions.

Lancelot of Yale – MS 229 f.180r – detail

Lancelot Grail – Royal 14E III f. 3 – detail of left column

Lancelot Grail – Royal 14E III f.3 – detail

Centre & Right – British Library – Lancelt Grail Prose Cycle – Royal 14E III fol 3 – possibly St. Omar or Tournai – early 14th century

To check out these manuscripts yourself, visit Royal 14E III – Lancelot Grail and ‘Lancelot’ of Yale MS 229