The celebrated Italian painters Giotto, Ambrogio Lorenzetti and Andrea di Bonaiuto painted dance images in the 14th century. As early as 1306 Giotto painted a fresco of a peasant couple dancing to the accompaniment of a musician. Another famous image is the fresco Allegory of Good Government in the Palazzo Pubblico of Siena (Ambrozio Lorenzetti circa 1338) shown below.

illustration 2 – Ambrozio Lorenzetti – detail from Allegory of Good Government – Palazzo Pubblico, Siena (1338)

Where Italian artists created magnificent fresco’s decorating the walls of churches and secular buildings, the artists and artisans of The Low Countries focused their creative skills towards illustrating illuminated manuscripts. The earliest manuscripts, Bibles, Psalters and breviaries, all had a liturgical function. In the course of the 14th century the Book of Hours, a book for private devotion, became fashionable and secular books namely, the Arthurian Tales, Le Roman de la Rose and the Romance of Alexander gained immense popularity. Paris, Bruges and the area now known as Northern France were the centres of manuscript production.

Dancers and musicians were a regular motif in the illuminated manuscripts. In this post I will look specifically at dancers drawn in the margins and most especially dancers standing, hanging, or suspended on some type of vine. These dancers, the so called marginalia, are some of the first dance images of The Low Countries.

The making of the manuscript followed a standard process; after the scribe had completed writing the text the manuscript was forwarded to the illustrator who added images in the space that the scribe had left vacant. The text was invariably surrounded by a variety of figures ranging from animals, knights, hybrids, dragons, monsters, birds, to musicians accompanying dancers. It was not unusual that musicians, tumblers, acrobats, and dancers were positioned on the outer edges of the folios. These wandering entertainers had a lowly reputation, lived on the outskirts of society and thus ‘lived’ in the margins of illuminated manuscripts. The written word was either partially or completely surrounded by some type of framing, be it vines, lines, foliage, tendrils, or circular flowing boundaries upon which a multitude of figures, including dancers and musicians, would intertwine. Dancers often appeared together with musicians. They performed back bends, stood on the shoulders on their partner, manoeuvred themselves on foliage, on vines, or formed gracious line terminals.

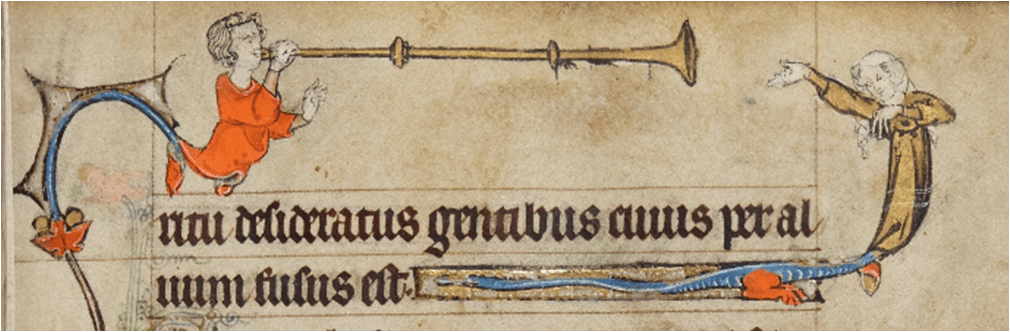

The above two illuminations come from an absolute gem; The Flemish Horae (MS B.11.22) to be found in the library of Trinity College, Cambridge. The 219 folios of this tiny manuscript (18 x 14.5cm) are for the most part lavishly decorated with delightful figures. Illustration 3, shows a half-figure musician emerging from a floral extension. His playing apparently pleases his lady friend, another half-figure arising from a dragon-like line ending. She sways gently in a soft backwards curve towards him. The artist has drawn her using a marked dark outline and emphasizes the folds of her dress. The face, headdress and hands, in contrast, are subtly outlined. Her face is delicately pencilled and she appears to be in a pleasant mood as she reaches out to the trumpeter. The dancer in illustration 4 appears less pleased. She hovers precariously on a vine suspended in strong forward pull. She looks as if she might fall at any moment. The string player is somehow balancing himself on the outer edge of an extension but he looks far from comfortable. And then there is the person occupying the initial. Is this a lady with a curly fringe or a tonsured monk? The occupant’s eyes are directed at the dancer. I would not be surprised if the attentive onlooker thoroughly disapproves of the dancing that is taking place.

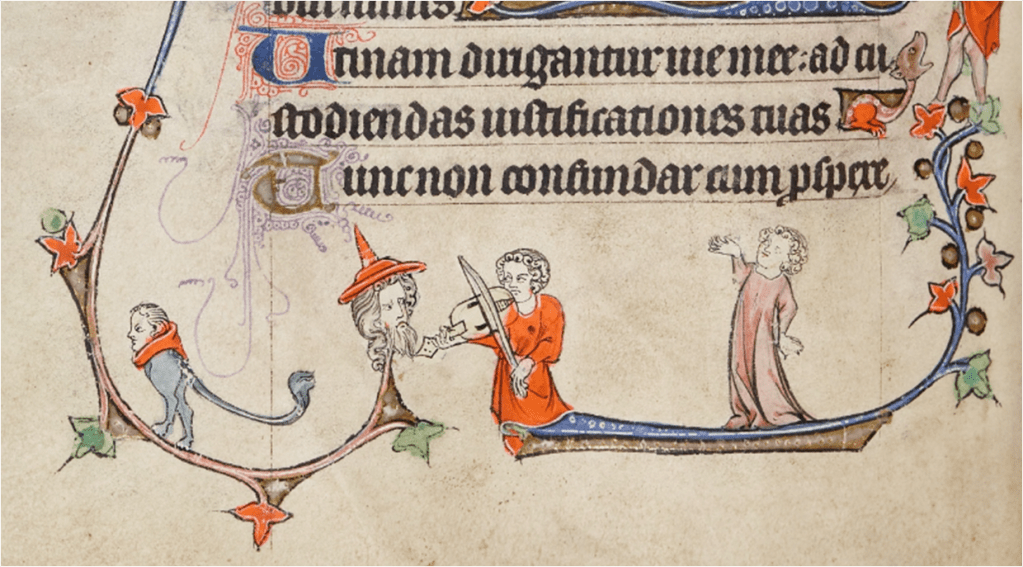

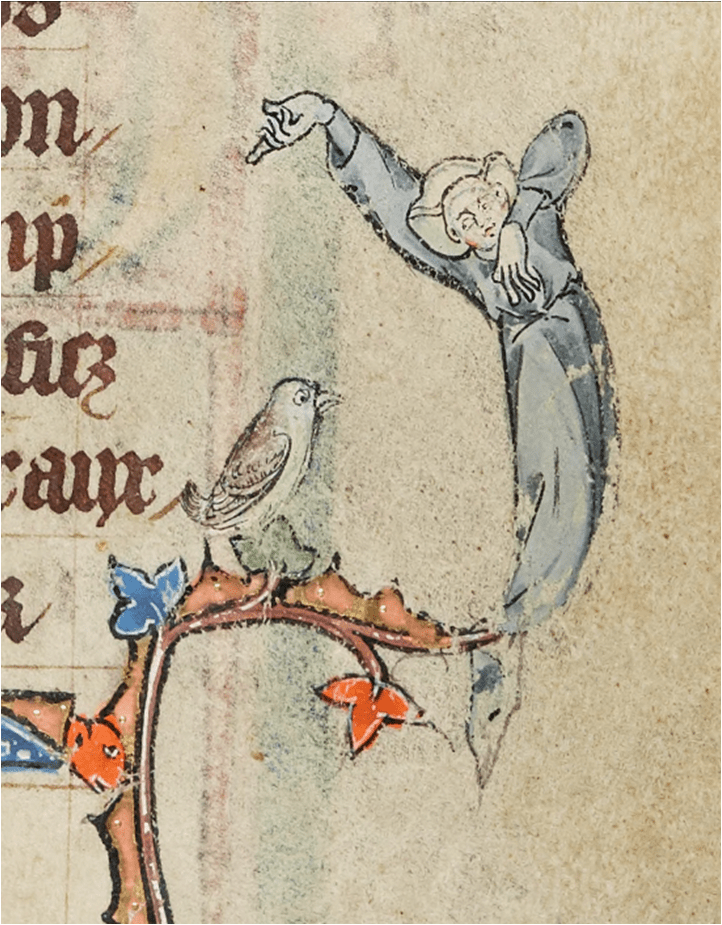

In another bas-de-page illumination (ill.5) the musician appears to be slightly irritated by the body-less bearded head figure who, for all we know, is criticizing his music. He nevertheless continues to play much to the pleasure of the dancing lady perched on the vine behind him. Last but not least, illustration 6 shows a dancer actually balancing on the edge of a vine. The artist has, as in the examples above, suspended her in a circular sway as she draws away from the disproportionately large bird that looks rather unhappy. This lady is very similar, both in appearance, movement and drawing technique, to the one in illustration 4. Each one of the dancers drawn by the anonymous artist of this Flemish Book of Hours captures a remarkable sense of movement. These are but four examples of the many unique and often curious marginalia to be discovered in this medieval manuscript.

The Flemish Horae MS B.11.22 is a fascinating manuscript containing various illustrations of musicians and dancing figures. The manuscript can be found online.